Exhibition: Community of Images

Documentation & Research

Gallery A, Gallery B, Gallery C & D, Gallery E, Gallery F, Closet, Checklist

Events, DÔME DO, WE—After Yukihisa Isobe’s Air Dome (1970)

Preservation Outcomes

Reviews

Videography by Rudy Gerson

Curators – Ann Adachi-Tasch, Go Hirasawa, Julian Ross

Community Engagement Lead – Rob Buscher

Curatorial Advisor – Nina Horisaki-Christens

Curatorial Assistant & Online Viewing Program Curator - Mia Parnall

Research Assistance – Emiko Inoue, Fusako Matsu, Shuhei Hosoya, Jon Kriney

Exhibition Design & Production Advisors – Michael Ciervo, Matt Suib, Aaron Igler, Nami Yamamoto

Exhibition Media Installations – Greenhouse Media

Design – Mielconejo D'Macedo

Marketing – Witty Gritty

Advisors: Christophe Charles, Gretjen Clausing, Rebecca Cleman, Frederick R. Dickinson, Riko Fujiwara, Antoine Haywood, Nadia Hironaka, Eikichiro Isobe, Barbara London, Mary Lucier, John McInerney, Takako Okamoto, Jesse Pires, Lia Robinson, Hirofumi Sakamoto, Naoko Seki, Akihiro Suzuki, Nobukazu Suzuki, Hiroko Tasaka, Kazumi Teune, Miwako Tezuka, Michèle Vicat, Yuka Yokoyama, Midori Yoshimoto

This project is organized by Collaborative Cataloging Japan (CCJ) and co-presented by CCJ and the Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia in partnership with Philadelphia Art Alliance. Major support has been provided by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, with additional support from the Andy Warhol Foundation, the Toshiba International Foundation, Pola Art Foundation, Pennsylvania Council on the Arts. Philadelphia Cultural Fund, and Japan Foundation.

Partners / Supporters:

Keio University Art Center

Fleisher Art Memorial

Lightbox Film Center

Mori Art Museum

PhillyCAM

Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation

Taki Kentaro, VIDEOART Center Tokyo

Twelve Gates Arts

University of Pennsylvania

©Albert Yee

Gallery A

Photographs by Constance Mensh

This gallery is anchored by research into Shelter 9999, a multiple projection, expanded cinema collaboration between Takahiko Iimura and Alvin Lucier, with Akiko Iimura and Mary Lucier participating in some performances as the four-person collective The Sparks. Delving into the archives of Takahiko Iimura’s studio and the New York Public Library, the presentation brings together elements of the work that had previously been dispersed. Akiko Iimura’s films were identified during research in Tokyo, which led to new digitizations of her films.

Takahiko Iimura (1937–2022) was a hugely influential avant-garde film and video artist. He was active in the arts in Tokyo beginning in the early 1960s and, starting with his first film, Junk (1962), was prolific in the avant-garde art scene. Having been introduced by artist Shigeko Kubota (Gallery E), Takahiko Iimura met and eventually married Akiko Iimura. Takahiko Iimura was a co-founder of the Film Indépendent group (Gallery F), and a pioneer of expanded cinema and film installations, with works like Dead Movie (1968, presented outside of Gallery F). He first went to the US in 1966 as a fellow for the Harvard University International Seminar in Boston, which was sponsored by the Asia Foundation in Tokyo. After his early work Love (1962)—soundtracked by Yoko Ono—was praised by filmmaker Jonas Mekas and caused a stir in the American underground, Iimura relocated to New York, where he would find several long-term collaborators, including composer Alvin Lucier.

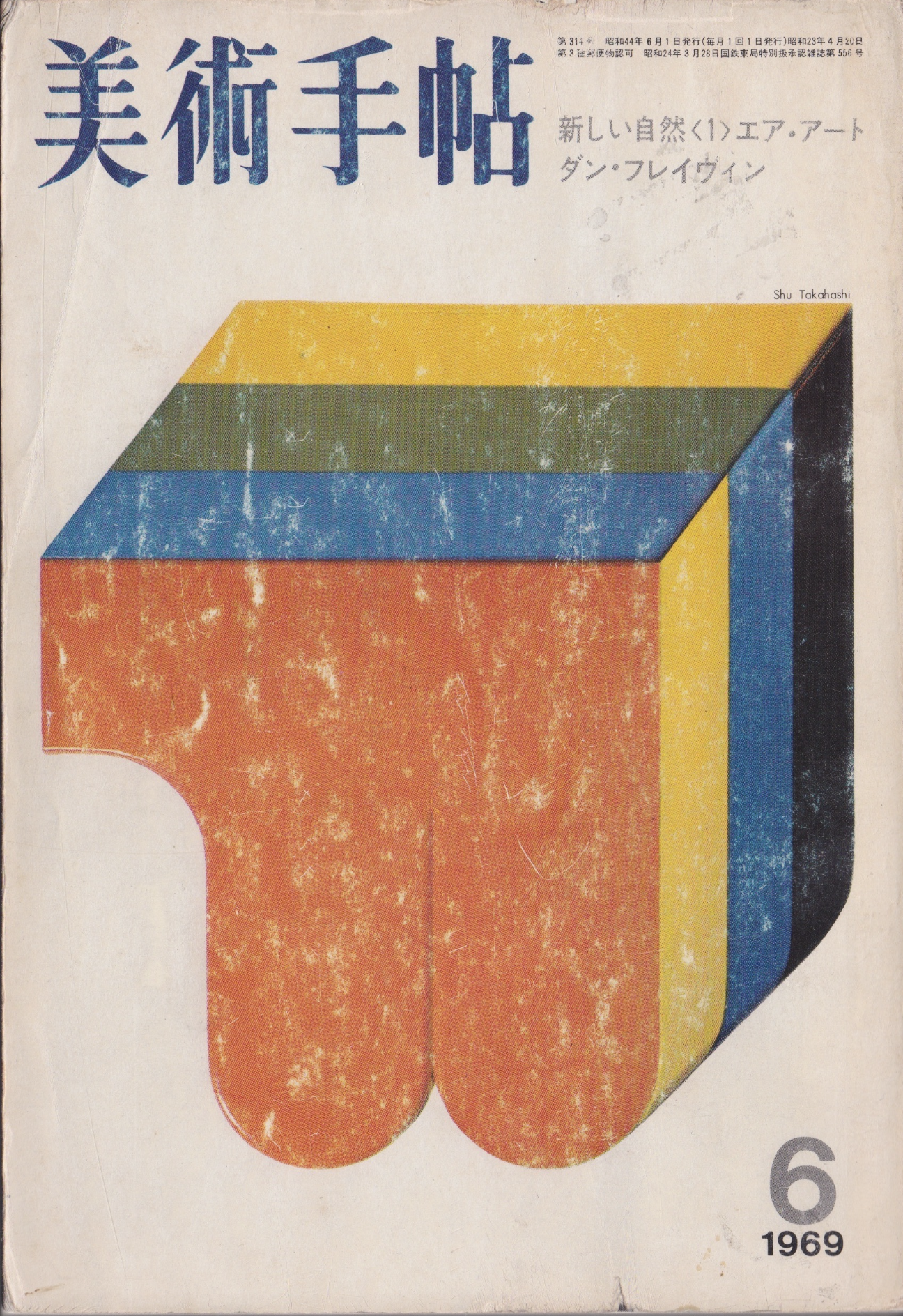

Akiko Iimura (b. 1936) is a writer, translator, and filmmaker who has spent much of her life in New York. She was the editor-in-chief of New York’s Japanese-language newspaper, OCS News, from 1982 to 1995. She graduated from Waseda University in Tokyo, where she studied French culture. In the early 1970s she was an active reporter on and translator of the New York underground scene for the Japanese journals Bijutsu Techō (Art Notebook) and Eiga Hihyō (Film Criticism). She was also instrumental in translating the writings of Jonas Mekas into Japanese.

Shelter 9999 and The Sparks: Takahiko Iimura, Akiko Iimura, Alvin Lucier, Mary Lucier

Having begun living in New York in the mid-1960s, Iimura was taken aback by the proliferation of “Shelter” signs throughout the city that pointed to the basements of buildings, signaling the American will to survive during the Cold War and its attendant feeling of anxiety. Iimura imagined a shelter of the future, which he titled Shelter 9999. In Japan, the word “underground” was removed from ordinary life and assumed its role as rhetoric, but in New York, the underground was directly associated with everyday life through the concept of the underground shelter.

Shelter 9999 was first performed in 1966 in collaboration with Alvin Lucier. Iimura used two 16mm film projectors and one slide projector; Lucier played electronic music and also used a large shell as an instrument. The performances took place at the Electric Circus in New York’s East Village, Gray Hall in Hartford, a church on the outskirts of Chicago, and an auditorium in Tokyo. In certain iterations, their partners Akiko Iimura and Mary Lucier joined in the performance.

Works in the Gallery

Archival presentation of Takahiko Iimura and Alvin Lucier, Shelter 9999, 1966–1968. Three projections and stereo sound comprising thirty-one color slides (looped); 16mm film transferred to digital video, 28:09 min, looped; three 16mm films transferred to digital, 9:28 min (total), looped; and stereo sound, 32:42 min, looped. Collections of Akiko and Takahiko Iimura, and Alvin Lucier papers, 1939–2015, New York Public Library Archives. Courtesy of the artists.

Akiko Iimura, Mon Petit Album, 1974. 16mm film transferred to digital video, 12 min, color, sound. Collection of the artist.

Takahiko Iimura, Taka and Ako, 1966. 16mm transferred to digital video, 13 min, b/w, silent. Collection of the artist.

Ephemera and photographs (all facsimile). Courtesy of Akiko and Takahiko Iimura, and Mary Lucier.

Instructions for Shelter 9999 on film can.

Electric Circus, New York. Photograph by Takahiko Iimura.

Takahiko Iimura.

Documentation photos of Shelter 9999.

From left to right: Takahiko and Akiko Iimura.

From left to right: Jyūshin Satõ and Takahiko Iimura.

From left to right: Akiko Iimura and George Kuchar.

From left to right: Yasunao Tone,Takahiko Iimura, Aldo Tambellini, Elsa Tambellini, Toshio Matsumoto.

From left to right: Alvin Lucier and Takahiko Iimura.

From left to right: Mary Lucier and Takahiko Iimura.

Akiko Iimura.

Program for Shelter 9999 performance as part of The Electric Ear at Electric Circus, 1968.

Poster for Sparks performance at the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque.

©Constance Mensh

Related Resources

Gallery B

Photographs by Constance Mensh

Having obtained permanent residency status in 1966, Yukihisa Isobe was in charge of work related to organizing events in New York’s public spaces when then-Mayor John Lindsey had unified the city’s culture, park, and recreation departments. Among the many events he helped organize was the Earth Day celebration, for which he mounted the Air Dome structure that housed discussions, music, film screenings, and dancing. Impressed by Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome and its way of connecting architecture to ecology and environment, Isobe enrolled in Professor Ian McHarg’s seminar at the University of Pennsylvania to study ecological planning, eventually writing his master’s thesis about ecological planning for Hart Island as the site of a therapeutic community.

Archival presentation of Dream Reel, a mixed media performance in Isobe’s Floating Theater

Originally presented at State University at Oneonta, March 23, 1969. Floating parachute and 16mm film transferred to digital video.

Due to lack of documentation and original media materials, a precise reconstruction of the performance work, which was a collaboration between Isobe and filmmaker Jud Yalkut, is not possible. The mixed-media performance was presented on March 23, 1969, at New York State University at Oneonta. According to Gene Youngblood, who wrote about Dream Reel in his book Expanded Cinema (1970), the original performance consisted of three sections: Paikpieces, Festival Mix, and Mixmanifestations.

Paikpieces incorporat[ed] the video-film collaborations between Yalkut and [Nam June] Paik…. Performance time is approximately fifteen minutes, set against the tape composition Mano-Dharma No. 8 by Takehisa Kosugi (1967) for two RF oscillators and one receiver. Equipment involves four to five 16mm projectors, including one with sound on film, four carousel slide projectors, and a stereo tape system. The contrast of Paik’s electronic imagery with the airy buoyancy of the silky enclosure produces an ethereal, evanescent atmosphere.

Festival Mix is a multiple-projection interpretation of the 1968 University of Cincinnati Spring Arts Festival…. In Dream Reel it involves three 16mm projectors, four carousel slide projectors, and a four-track stereo tape system on which is played Festival Mix Tape by Any Joseph and Jeni Engel. Sounds and images include those of Peter Kubelka, Charles Lloyd, Bruce Maillie, Nam June Paik, Charlotte Moorman, Ken Jacobs, Hermann Nitsch’s Orgy-Mystery Theater, Paul Tulley, The Fugs, Jonas Mekas, and the MC-5. “I was unnerved and numb from the tremendous impact this had on my senses,” one person commented after the performance.

Mixmanifestations, the most complex section of Dream Reel, is described by Yalkut as “a nonverbal communion and celebration for all channels within a totally surrounding environmental performance.” Visual elements include an exploding hydrogen bomb, the Living Theater, the Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, Yayoi Kusama (from Yalkut’s film Self Obliteration), and various be-ins and peace marches. These are blended and juxtaposed with abstract meditational motifs culminating in a centralizing mandalic experience utilizing both visual and aural loop techniques for the alternating pulse and phase-out of simultaneous temporal interference fields. The twenty-minute performance includes four to five 16mm projectors, two 8mm projectors, four carousel slide projectors, and two four-track stereo tape systems for the simultaneous playback of tapes and tape-loop cartridges.

—Gene Youngblood, Expanded Cinema (New York: Dutton, 1970), 391-92.

In this presentation, Yalkut’s video-film, produced collaboratively with Nam June Paik, is projected onto Isobe’s reconstructed Floating Theater. Films by Yalkut featuring Isobe’s works are shown on smaller monitors.

Yukihisa Isobe (b. 1935) began his career as an avant-garde painter in Japan before relocating to New York in 1965, where he moved into the field of urban and ecological planning. In the summer of 1965, after going to Venice for a solo gallery exhibition, Isobe traveled around Europe, continuing on to New York where he decided to settle, remaining in the US until the mid-seventies.

Isobe was already using modular constructions made of wood when he saw Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome at the Montreal Expo 67 and became interested in new materials and structures. While he initially explored tent and hanging structures, he gradually focused on constructing air structures using vinyl. His Double Skin Structure (1968) was presented in the 1968 exhibition Some More Beginnings: Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) at the Brooklyn Museum. His interest in air as a material for art next led him to create the Floating Theater, a canopy-shaped parachute held aloft by air blown from below. In Dream Real, a multimedia performance undertaken in spring 1969, filmmaker Jud Yalkut projected multiple film and slide images on Isobe’s Floating Theater, incorporating sound by various composers. During the same period, Isobe collaborated with light art artists Jackie Cassen and Rudi Stern in producing Theater of Light.

After embarking on a project using a hot air balloon through his employment with the New York City Parks Department, Isobe was invited to participate in organizing the Summer Happening in New York City’s Hart Island for Phoenix House, a drug and alcohol rehabilitation facility. He collaborated with David Behrman in 1969 on a balloon-driven remote audio feedback system which served as the basis for their unrealized Pepsi Pavilion event proposal for Expo ’70. His project Air Dome was a temporary interactive structure installed in Union Square in 1970 in honor of Earth Day.

In 1970, he enrolled in Professor Ian McHarg’s seminar at the University of Pennsylvania to study ecological planning, eventually writing his master’s thesis about ecological planning for Hart Island as the site of a therapeutic community for Phoenix House. Assisting Professor McHarg—who provided consultation to Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Transportation—in the planning of an industrial city for the Yonezawa Basin, Isobe became involved in a variety of environmental assessment and ecological planning work in Japan. McHarg’s philosophy of regional planning—that land use should be determined according to the environmental features of each region—and his approach to planning guided by the mutual, long-term relationship between a region’s environment and human culture in mind, have formed the core of Isobe’s work until this day.

Information about Isobe’s work since the 2000s is detailed in Naoko Seki’s essay, published on the project website.

Works in the Gallery

Archival presentation of Dream Reel, a mixed media performance in Isobe’s Floating Theater, originally presented at State University at Oneonta, March 23, 1969. Parachute and 16mm film transferred to digital video. Courtesy of Yukihisa Isobe, the Jud Yalkut Estate, and Anthology Film Archives.

Film documentation of Yukihisa Isobe’s work by Jud Yalkut. 16mm film transferred to digital video. Courtesy of Jud Yalkut Estate and Anthology Film Archives.

©Constance Mensh

©Albert Yee

Archival Materials in the Gallery

Ephemera and photographs (all facsimile). Courtesy of Yukihisa Isobe and Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo.

Yukihisa Isobe’s Double Skin Structure (1968) was presented in the 1968 exhibition Some More Beginnings: Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) at the Brooklyn Museum, in collaboration with filmmaker Masanori Ōe. During the same period, Isobe collaborated with light art artists Jackie Cassen and Rudi Stern in producing Theater of Light at Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut.

Through his employment with the New York City Parks Department, Isobe helped in organizing the Summer Happening in New York City’s Hart Island for Phoenix House, a drug and alcohol rehabilitation facility. His project Air Dome was a temporary interactive structure installed in Union Square in 1970 in honor of Earth Day.

Yukihisa Isobe’s Double Skin Structure 1, exhibited during the Some More Beginnings: Experiment in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) exhibition, Brooklyn Museum, New York, 1968.

Double Skin Structure 1, 1968.

Floating Theater, 1969.

Dream Reel, a mixed media performance in Isobe’s Floating Theater by Jud Yalkut and Yukihisa Isobe, State University of New York at Oneonta, 1969.

Flier for Dream Reel, a mixed media performance in Isobe’s Floating Theater.

Flier for Theater of Light by Rudi Stern and Jackie Cassen. Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut, 1969.

Yukihisa Isobe at Theater of Light event.

Theater of Light event.

First Earth Day at Union Square, New York, 1970.

First Earth Day at Union Square.

Inside the Air Dome at the first Earth Day.

Yukihisa Isobe setting up the Air Dome at the first Earth Day.

Poster for Environmentals: Man/Art/Community event at Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut, 1970.

Air Dome at Environmentals: Man/Art/Community event.

Air Dome at Environmentals: Man/Art/Community event.

Air Dome at the second annual Phoenix House Summer Happening at Hart Island, 1970.

Ushio Shinohara (center) and Yukihisa Isobe (center right) in the Air Dome at the second annual Phoenix House Summer Happening, 1970.

Yukihisa Isobe at the second annual Phoenix House Summer Happening, 1970.

Third annual Phoenix House Summer Happening at Hart Island, 1971.

Production of the Air Dome for the third annual Summer Happening, 1971.

Inside the Air Dome at the third annual Summer Happening, 1971.

Inside the Air Dome at the third annual Summer Happening, 1971.

Outside the Air Dome at the third annual Summer Happening, 1971.

Related Resources

Gallery C & D

Photographs by Constance Mensh

The artists in galleries C and D traveled to the US in the mid-1960s, where they encountered and processed different aspects of American art, culture, and politics in their work: Fluxus and experiments in film and sound for Takehisa Kosugi and Seiichi Fujii; class and racial segregation for Kenji Kanesaka; and psychedelia and political activism for Masanori Ōe.

In the US, the anti-establishment movement gained momentum in the 1960s as the civil rights movement made significant progress and the intensification of the Vietnam War that same year spurred new anti-war protests that overtook college campuses and flooded mass media. In Japan, as politics and society underwent a major transformation through the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty struggle in 1960, new expressions that differed from conventional art and culture emerged in film, music, and art. These movements transcended the framework of Japan, resonating with American avant-garde art, underground cinema, and hippie culture.

Takehisa Kosugi collaborated with Fluxus artists after his move to New York City in 1965. After his return to Japan in 1967, he co-founded a multimedia improvisation music group called Taj Mahal Travellers in 1969. In this exhibition, we have digitized Body Wave (1970), a film by Seiichi Fujii about Kosugi and the Taj Mahal Travellers on multiple projection, along with TM (1974), Kosugi’s only film directorial piece. Kenji Kanesaka initially began photo-documenting Black communities in Chicago as part of the cultural landscape he witnessed upon first coming to America, eventually expanding to films that analyzed the complex systems of oppression that urban Black communities faced. Masanori Ōe, enmeshed in the hippie movement, observed the dynamics between white hippies, yippies, and radical communities of color from his perspective as a Japanese immigrant.

Takehisa Kosugi (1938–2018) was a composer, performer, and founding member of Group Ongaku along with Yasunao Tone, Mieko Shiomi, and others. Toshi Ichiyanagi advised Kosugi and the group to send recordings to George Maciunas, which marked the start of their involvement with the Fluxus movement in the early 1960s. After Kosugi moved to New York City in 1965, he collaborated with international Fluxus artists like Nam June Paik and Charlotte Moorman. A notable performance from this period is Kosugi’s Film & Film #4 (1965), in which light is projected onto a paper screen that the artist—who stands behind it—cuts a square shape out of, starting in the center and gradually enlarging it until only the edges of the frame remain. Kosugi returned to Japan in 1967 and co-founded the multimedia improvisation group Taj Mahal Travellers in 1969. The Taj Mahal Travellers participated in the Utopias & Visions 1871–1981 exhibition in Stockholm in 1971, and toured Europe, Southwest Asia, and North African in a van, finally arriving at the Taj Mahal in India. TM, a film work by Kosugi, was made for the first 100 Feet Film Festival organized by Image Forum in 1974. Composed of images shot in Tokyo with a unique perspective and rhythm, TM is Kosugi’s first work using film material.

Seiichi Fujii (b. 1948) was a member of the collective Video Hiroba and the creator of Body Wave, an experimental film about Takehisa Kosugi and the Taj Mahal Travellers shot in 1970 in Ōiso Beach. Fujii exhibited his work in various locations in Japan and the US throughout the 1970s, including Millennium Film Workshop in New York, Canyon Cinematheque in San Francisco, and the Pacific Film Archives in Berkeley. He participated in the 1975 Video Art exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia with his work Mantra (1973). The documentation of his performance, Kite—in which a wireless mic was installed on a kite and sound was emitted while the kite was in the air by a beach—is presented in Gallery F.

Kenji Kanesaka (1934–1999) came to the US through the Harvard University International Seminar and lived in Illinois while attending Northwestern University. Kanesaka encountered iconic underground figures such as Allen Ginsberg and Andy Warhol and photographed America's newly emerging social groups in the 1960s, from the hippies to the Black Panthers. His film work also explored the complex makeup of America’s cultural landscape along lines of race and class. His landmark film Super Up (1966), titled America, America, America in Japan, was made in collaboration with Chicago producer Marv Gold and tells the story of an African American teenager lost in the world of commercialism and advertising. As it depicts a young African American character, the film is a critique of racial and class inequities, as well as consumerism, desire, and the police. Kanesaka is said to have popularized the term angura, a Japanese abbreviation of the word “underground,” in Japan.

Masanori Ōe (b. 1942) moved to New York in 1965 and immediately visited Timothy Leary’s psychedelic show, which Allen Ginsburg and Richard Alpert (Baba Ram Dass) also attended. Ōe collaborated with the Newsreel collective, a group of filmmakers, photographers, and media artists who worked within and across mediums to provide alternative news coverage of world events and anti-establishment movements at the time. Working with Marvin Fishman at Studio M2, he entered film production. In April 1967, Fishman and Oē filmed the Be-In, an event held in New York that focused on personal empowerment, communal living, ecological awareness, higher consciousness (with the aid of psychedelic drugs), and leftist political consciousness. The resulting film, Head Games, spoke to the dissonance between the nature of such an event—with its costumes, rituals, and discourse—and the actual war this event was intended to be protesting. In contrast, the International Anti-War Day demonstrations at the Pentagon in Washington DC held in October of that same year turned violent, inspiring the title of the work No Game. In 1967, CBS commissioned Ōe and Fishman to create an overview of the entire decade, for the annual CBS network convention in New York, and granted them permission to use footage from the CBS archive. They produced Great Society, a six-screen collage of newsreel footage showing the multifarious views of the time. The piece featured images of soldiers marching, of the JFK and Oswald assassinations, of sixties fashion, NASA, civilian casualties in Vietnam, fighter jets dropping bombs, and politicians speechifying.

Works in the Gallery

Takehisa Kosugi, TM, 1974. 16mm film transferred to digital video, 3 min, color, silent. Courtesy of the Estate of Takehisa Kosugi

Seiichi Fujii, Body Wave, 1970. 16mm film transferred to digital video, double projection, 35 min, b/w and color, sound. Courtesy of the artist.

Kenji Kanesaka, Super Up, 1966. 16mm transferred to digital video, 13 min, color, sound. Courtesy of the artist and the Chicago Film Archives.

Masanori Ōe and Marvin Fishman, Great Society, 1967. Six projection 16mm film transferred to digital video, 17 min, color, sound. Courtesy of the artist and S.I.G.

Masanori Ōe, Head Game, 1967. Film transferred to digital video, 10 min, color, sound. Courtesy of the artist and S.I.G.

Masanori Ōe, No Game, 1967. Film transferred to digital video, 17 min, b/w, sound. Courtesy of the artist and S.I.G.

Related Resources

As part of the Japanese Expanded Cinema research thread, CCJ partners Go Hirasawa and Hiroko Tasaka interviewed filmmaker Masanori Ōe in 2017. Hiroko Tasaka organized the exhibition Japanese Expanded Cinema Revisited at Tokyo Photographic Art Museum in 2017, which included Oe’s Loop Siki No.1 / No.2 / No.3 (1966). Go Hirasawa was the curatorial adviser in the exhibition.

Gallery E

Photographs by Constance Mensh

In the 1960s, on the tail of the civil rights movement, second-wave feminism emerged as a viable development in the US. As women’s struggles came into the mainstream with the advent of the contraceptive pill in 1961, and bills such as the Equal Pay Act of 1963 wrote greater equality into law, radical movements such as Women’s Liberation combined feminism with leftist politics, viewing gender inequalities through a systemic lens, as captured in the popular phrase “the personal is political.” Yet many minority women found mainstream groups like the National Organization for Women unwilling to address intersectional issues, prompting the establishment of separate organizations, often led by Black women, to confront feminism’s intersections with class, race, and imperialism, and the concerns of other political and countercultural groups.

At the same time, during the 1960s and 1970s, the diplomatic links between Japan and the US were the subject of public contention. Japan and its military bases were a key US asset during the Cold War due to their relative proximity to, and thus convenience for, launching military actions in Vietnam and Southeast Asia. Joined by a host of other reasons including anti-democratic political shenanigans in the National Diet and authoritarian crackdowns on the use of public space, the Japanese state’s apparent subservience to US desires sparked and prolonged student protests against the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty (ANPO) throughout the greater 1960s. Since the Pacific War, American cultural influence in Japan had brought about changes in entertainment and fashion, but US military presence had also become a source of base-related violence and unregulated sex work and had led to the destruction of villages for US-sponsored infrastructure. This fomented a sense of powerlessness at an individual level and an impression of collusion at the state level. Japanese artists living in the US were keenly aware of these tensions and, in traveling to America, gained new perspectives on a culture they had already experienced obliquely.

Japanese women artists in the US like Mako Idemitsu, Kyōko Michishita, and Shigeko Kubota were not only key figures for fostering the exchange of feminist ideas between the US and Japan in the late 1960s and early 1970s; as they acquired identities as women of color in the North American context, they could also offer a critical perspective on the state of US feminism. Through their exchanges and translations of feminist media, subversive uses of technology, and participation in male-dominated cultural spaces, they produced both direct and indirect critiques of gender politics in both countries. While conscious of the sexism prevalent within Japanese society—which, for example, inspired Michishita to work on translating American feminist ideas into Japanese—they were also critical of chauvinism and other asymmetrical power relations in the US. Power imbalances in the mediasphere inspired Fujiko Nakaya’s first video in early 1972. As a founding member of the Video Hiroba collective, she saw video as a technology for change, incorporating this perspective into her work, Friends of Minamata Victims - Video Diary. Nakaya used the liveness of the video medium to replay the actions of protestors at Chisso Corporation’s headquarters back to themselves and create a new sense of their own power and autonomy by placing them on the television screen. Video thus became a space for women video makers to address issues of power and identity.

Mako Idemitsu

Escaping her patriarchal family in Japan, Mako Idemitsu (b. 1940) relocated to New York in the early 1960s, later moving to California, where she established a family with her husband, the artist Sam Francis. Her creative pursuits in writing stalled, however, as she faced language barriers and took on her new responsibilities as a wife and mother of two. Finding that she was often viewed only as a mother or “the artist’s wife,” Idemitsu struggled to find an identity of her own. Out of desperation to create, Idemitsu bought an 8mm film camera in the late 1960s and began to observe and capture her surroundings, utilizing film as her new creative outlet. She made two works in 8mm in 1970, and in 1972, began experimenting in 16mm. She encountered video when she relocated back to Japan for a year. There, she received an invitation to be part of the January 1974 show Tokyo-New York Video Express—a collaborative project by Shigeko Kubota and Video Hiroba. Nobuhiro Kawanaka instructed Idemitsu on how to use a video camera, which led her to make What a Woman Made, the artist’s seminal video of a tampon in a toilet, a sarcastic reflection on the rhetoric she was brought up with, denied women’s ability to produce art.

Idemitsu’s interest in exploring women’s identity was cultivated during her final years living in Santa Monica, California, and in the first decade following her return to Tokyo in 1973. Just before she went back to Japan, she encountered and documented the Judy Chicago-led collective installation at Womanhouse (which Idemitsu edited as Woman’s House), around the same time she started reading the writings of psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung. Back in Japan, she continued to investigate identity, the unconscious, and gender relations in her films and early video experiments. Around 1977, Idemitsu frequented the feminist gathering space Hōkiboshi in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district, and asked four women to participate in her work, Women. She handed them each a video camera to film whatever they wished, and at the same time Idemitsu recorded their actions. The whole group then watched the five videos on five monitors (the four women’s videos and Idemitsu’s recording of their actions), which Idemitsu also documented on video. Displayed across six screens (including the video of them watching), the final six-channel video installation presented an exchange of gazes through which Idemitsu explored the psychology of women’s sociality. The scenes that each woman prepared, their camera movement, their view from the lens, and their reaction to watching each other’s videos comprise the basis for this exploration of the intersection of the personal and the collective. The videos of Idemitsu’s documentation are missing, and the current version is four-channel.

Kyōko Michishita

While a number of artists moved abroad to investigate America, others also took the opportunity to gain a fresh perspective on Japan, adopting a more observational stance toward the phenomena of their home country upon their return. Kyōko Michishita (b. 1942)—who went to the US for high school and then studied journalism at the University of Wisconsin-Madison before serving as a guide at the United Nations headquarters in New York—explored gender politics during her time in the US. Upon her return to Japan, she began working first for Expo ’70 and then for the American Center in Tokyo, where she curated arts programming, including exhibitions and events. It was there that she met the Video Hiroba collective and became inspired by video as an alternative space for public discourse, subsequently making a series of works exploring the gender dynamics of family politics in Japan. Recognizing the limits of simply imposing American feminism onto the Japanese context, she investigated rural communities and unique individuals in search of an autochthonous form of liberation for Japanese society.

Alongside translating seminal American feminist authors from Gene Marine to Gloria Steinem into Japanese, Michishita produced video works that gathered a multiplicity of perspectives on gender identity from within Japan. One of her early works, Let’s Have a Dream (1974), documented a performance by Yoko Ono in Tokyo, using the intimacy of the portable black-and-white video camera to capture Ono’s intense stage presence as a reflection on transgressions of gender norms. The series Being Women in Japan (1973–74) explored the everyday lives of women, documenting both a seaweed farming community in Hokkaido (Living with the Ocean) and how a health crisis impacted Michishita’s own sister’s family (Liberation within My Family). Her series of interviews dating from the early 1980s, Video Portraits: Men, profiled positive models of masculinity from within the Japanese artistic community.

©Albert Yee

©Albert Yee

Shigeko Kubota

Beginning her career in Japan, Shigeko Kubota (1937–2015) moved to New York in 1964 along with fellow artist Mieko Shiomi due to her frustration that her work was not receiving proper attention in Japan, and her belief that the situation would not improve in the future. Having seen a performance by John Cage in Tokyo in 1962 and having become acquainted with Yoko Ono, Kubota began a mail correspondence with George Maciunas while still in Japan. After relocating to New York, she became a key organizer for the Fluxus movement, dubbed its “Vice Chairman” by Maciunas himself. Kubota was a fixture of the Fluxus community, participating in various Fluxus events, including her infamous Vagina Painting (1965), and produced her own Fluxus objects. Kubota also joined the experimental music group Sonic Arts Union (1966–76), with which she traveled internationally in 1969. The group consisted of four couples: Gordon Mumma and Barbara Dilley; Mary Lucier and Alvin Lucier, David Behrman and Shigeko Kubota; and Robert Ashley and Mary Ashley. It is in this context that Kubota became friends with Mary Lucier.

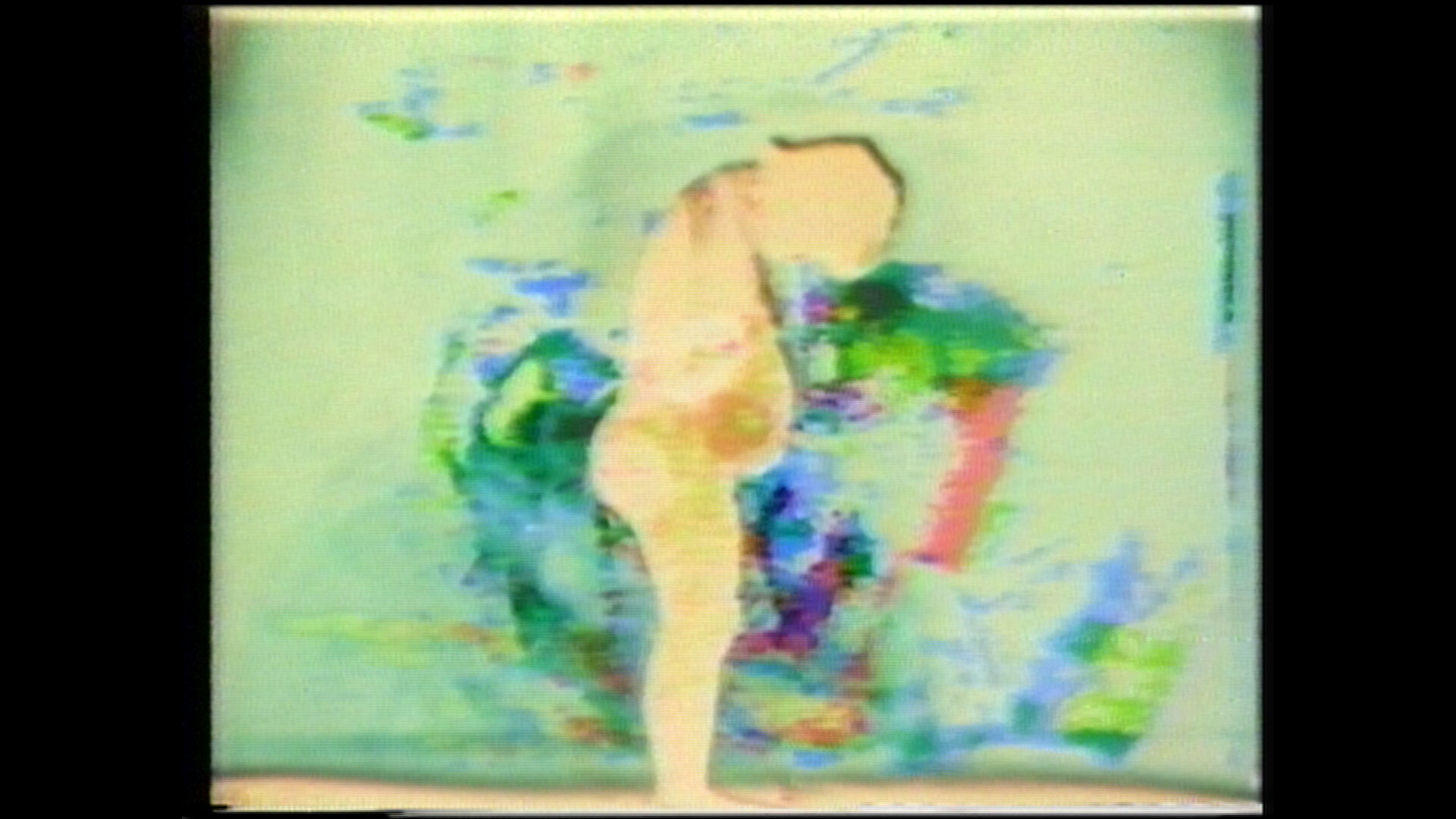

In the early 1970s, Kubota began exploring video as a new medium. She became known for innovating a form she called video sculpture, which unified video and three-dimensional sculptural forms. Her first experiments with a video camera were manipulated close-up self-portraits made using the Paik/Abe Video Synthesizer, a technology invented while she, Paik, and artist Shuya Abe were teaching art CalArts in 1970 and 1971. Her relationship with Nam June Paik developed into a marriage in 1977, and their partnership continued for thirty years, until Paik’s death. Her major video sculpture series include Duchampiana (1972–75) and a body of works experimenting with nature and landscape forms and traditions. In parallel, she developed a series of single-channel autobiographical pieces entitled Broken Diary (1969-86).

Kubota’s practice often touched on aspects of identity, subjectivity, and social relations in American life. In 1972–1973, she formed the coalition Red, White, Yellow & Black, along with Mary Lucier, Cecilia Sandoval, and Charlotte Warren. The four women artists from four different racial identities realized that male experimental artists often gained recognition as collectives and sought to create a similarly inclusive space for themselves. In 1973 Kubota lived for a month with a Navajo family (Cecilia Sandoval’s) in Chinle, Arizona, documenting her stay, which ultimately inspired her work, Video Girls and Video Songs for Navajo Sky (1973).

Kubota also acted as a go-between, reporting on the underground art scene for Japanese periodicals such as Bijutsu Techō (Art Notebook) and curating exhibitions to facilitate artistic exchange—most notably the 1974 exhibition Tokyo-New York Video Express presented at Shinjuku’s Tenjō Sajiki Hall, in collaboration with the Tokyo-based collective Video Hiroba. Kubota brought videotapes with her from New York to Tokyo to introduce artists such as Douglas Davis, Dennis Oppenheim, Charlotte Moorman, Shirley Clark, and many others, alongside new works by the members of Video Hiroba. Kyōko Michishita’s review of the Tokyo-New York Video Express is presented in the exhibition and available in the resources link.

In 1974 Kubota founded the video program at Anthology Film Archives at the request of Jonas Mekas. From 1974 to 1982 she served as Anthology’s first Video Curator, where she played an instrumental role in showcasing emerging video art. In 1974, the same year Kubota took on this curatorial role, The Museum of Modern Art held the Open Circuits: An International Conference on the Future of Television conference. Organized in response to an increasing resistance to video art by the museum’s community, the conference sought to present an international perspective on the vibrant experimentation happening in this new medium; Kubota was enlisted to present on women’s contributions to the field. Alongside her curatorial work at Anthology, Kubota organized Video Talk Shows, a forum for discussion, starting in 1976. The series serves today as a window into video art’s development in New York from the mid-1970s through the early 1980s. Early in the series, the most urgent topic was the impact of the emergence of video on the film-dominated field of moving-image production, with participants musing on video’s future direction. The theme of the December 1977 Video Talk Show was “The Future of Video”—an examination of the state of video within museum institutions, which were represented by speakers on staff at MoMA, the Whitney Museum, and the University Art Museum at UC Berkeley. By the early 1980s, however, the series’ themes were primarily dedicated to the economics of producing video art and formal and aesthetic directions for video (themes included “Economics and Video Art: Problems and Opportunities” moderated by Jaime Davidovitch, July 28, 1981; “Video Editing and Video Animation Workshop,” April 17, 1983; “Video and Photography,” January 16, 1982). A total of three Video Talk Shows have been digitized by the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation to date, from which we will present the opening remarks of two events (March 1977 and December 1977 events):

May 22, 1976, with David Ross and Hollis Frampton

March 23, 1977, with Suzanne Delehanty and Gerald O’Leary

December 18, 1977, with David Ross, Barbara London, John Hanhardt, and Jonathan Price

Ephemera and photographs (facsimile) related to Shigeko Kubota. Courtesy of the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation, Mary Lucier, Bill Nichols, Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, and the Mori Art Museum.

In the mid-1960s, Shigeko Kubota joined the experimental music group Sonic Arts Union (1966–76), with which she traveled internationally in 1969. Within this context, Kubota met and became friends with Mary Lucier. In 1974 Kubota began curating video exhibitions at Anthology Film Archives and elsewhere to facilitate artistic exchange. ost notably, she organized the 1974 exhibition Tokyo-New York Video Express presented at Shinjuku’s Tenjō Sajiki Hall, in collaboration with the Tokyo-based collective Video Hiroba. Kubota brought videotapes with her from New York to Tokyo to introduce artists such as Douglas Davis, Dennis Oppenheim, Charlotte Moorman, Shirley Clark, and many others, alongside new works by members of Video Hiroba. Kyōko Michishita’s review of the Tokyo-New York Video Express is presented in the exhibition and available in the resources link.

Photograph of the Sonic Arts Union during their tour to Aquila, Italy, 1969. From left to right: Gordon Mumma, Barbara Dilley, Mary Lucier, Alvin Lucier, David Behrman, Shigeko Kubota, Robert Ashley, Mary Ashley. Photographer unknown.

Mary Lucier and Shigeko Kubota, Zagreb, Croatia, 1969. Photographer unknown.

Photograph of the White, Black, Red, and Yellow event planning session, 1973. Auto-photograph by Mary Lucier. From left to right: Mary Lucier, Charlotte Warren, Cecilia Sandoval, and Shigeko Kubota.

Poster for White, Black, Red, and Yellow event at the Kitchen, New York, 1973.

Program for White, Black, Red, and Yellow event at the Kitchen, New York, 1972.

Program for White, Black, Red, and Yellow event at the Kitchen, New York, 1973.

Photograph of Shigeko Kubota and Mary Lucier.

Photograph of Shigeko Kubota and Mary Lucier.

A note by Shigeko Kubota.

Photograph of Shigeko Kubota. Photographer unknown.

Poster for Tokyo-New York Video Express at Underground Cinematheque at Tenjō Sajiki Hall, Tokyo, 1974.

Program notes for Tokyo-New York Video Express.

Program notes for Tokyo-New York Video Express.

Program notes for Tokyo-New York Video Express.

Photograph of the Tokyo-New York Video Express event. Photograph by Katsuhiro Yamaguchi.

Photograph of the Tokyo-New York Video Express event. Photograph by Katsuhiro Yamaguchi.

Photograph of the Tokyo-New York Video Express event. Photograph by Katsuhiro Yamaguchi.

Women and Film, 1, no. 5-6 (1974). Includes Kyōko Michishita’s article, “Tokyo-NY Video Express.”

A thank you note from Shigeko Kubota to Kyõko Michishita for her article in Women and Film.

Season calendar for Video Art program at the Anthology Film Archives, November–December, 1977.

Program list including Video Talk Show, 1976–1977.

©Albert Yee

©Albert Yee

©Albert Yee

Fujiko Nakaya

Fujiko Nakaya (b. 1933) was a founding member of the collective Video Hiroba, which saw video as a technology for change. She was instrumental in recruiting members to the collective and organizing access to technology for their first exhibition, Video Communication: Do-It-Yourself-Kit, held in early 1972 at the Sony Building in Ginza. For this show, Nakaya made her first video work, Friends of Minamata Victims - Video Diary, which uses the liveness of the video medium to replay the actions of protestors at Chisso Corporation's headquarters back to them on a portable monitor. By showing the protestors images of their own actions on the television screen—a novel experience in the early 1970s—the project fostered a new sense of their own power and autonomy. In the months after Video Communication: Do-It-Yourself-Kit, Nakaya went on to document a rock concert held to raise funds for a Jishu-Kōza Citizens’ Group delegation to attend the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, and then sent tapes to be screened by the delegation at an activist event accompanying the conference. A letter from the hosts of this screening event was printed in the first issue of Video Hiroba’s self-published journal.

Nakaya’s understanding of the problems of ecology were complex and structural. Her entry into video was preceded by her work coordinating Experiments in Art and Technology’s Pepsi Pavilion at Expo ’70 as well as the Tokyo branch of the E.A.T.’s 1971 transnational telex project Utopia Q&A, 1981. She was deeply aware of the power of communications technology, and her entry into video stands as an outgrowth of this understanding. Writing in 1974 about why she felt it important to publish a Japanese translation of Michael Shamberg’s infamous DIY video handbook, Guerilla Television, Nakaya draws a parallel between Japan and “Media America,” referring to the island nation as an “information-polluted archipelago” (jōhō kōgai resshima). In this single term, Nakaya encapsulates her vision of the inextricable nature of media and natural ecologies, tying the pollution problems of rapid postwar industrialization and urbanization to the highly managed highly managed media infrastructures that flourished in 1960s Japan. Such perspectives on the meaning and possibilities of video motivated Nakaya’s involvement in Video Hiroba’s collectively produced community projects, including designing a video communication process for a city-run urban planning project in Yokohama and reimagining a PR Center as a community space for the Niigata branch of the Tohoku Electric Power Company. Nakaya continued to play a key role in the development of video in Japan both through her own experiments as an artist and her organizational roles, which included researching the alternative possibilities of rural cable networks in the late 1970s, serving as a juror for video festivals, and running the preeminent video venue in Tokyo—Video Gallery SCAN—from 1980 to 1992.

Nakaya spent her college years at Northwestern University and continued to visit the US regularly after returning to Japan in 1959. As she was fluent in English, she was enlisted as a translator for events, including Robert Rauschenberg’s performance at Sōgetsu Art Center in 1964. She also served as a performer in Deborah Hay’s Solo, a performance work presented at 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering in 1966. These events led E.A.T. founder Billy Klüver to invite Nakaya to serve as the group’s Japan-based coordinator in the lead-up to Expo ’70. Such experiences positioned Nakaya as a key conduit of exchange between the experimental scenes in New York and Tokyo.

Guerrilla Television by Michael Shamberg and Raindance Corporation, first published in 1971 by Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York. Translated into Japanese by Fujiko Nakaya and published in 1974 by Bijutsu Shuppan-sha, Tokyo. Private Collection.

©Albert Yee

©Albert Yee

©Albert Yee

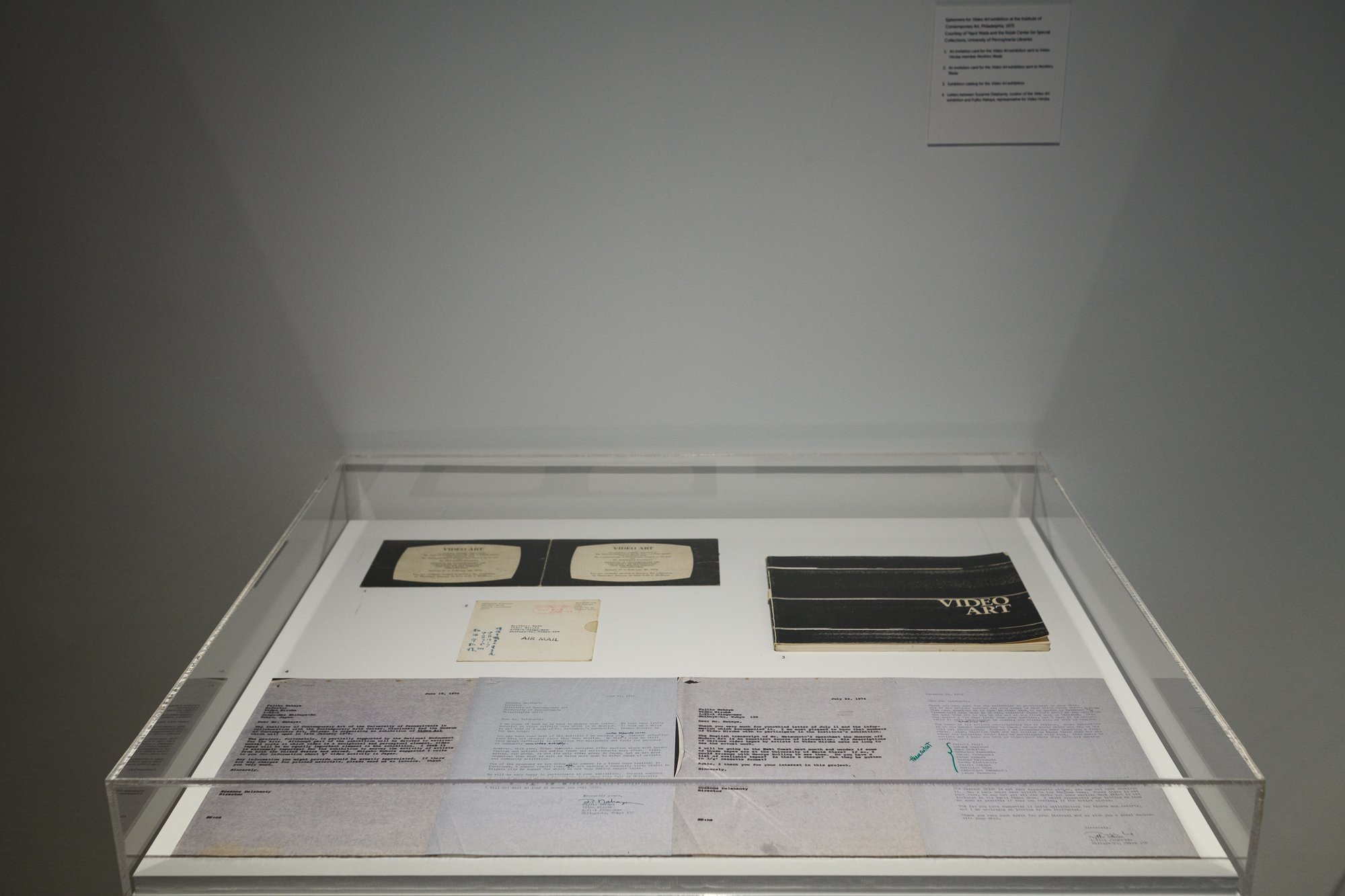

Ephemera for Video Art exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia, 1975. Courtesy of Yayoi Wada and the Kislak Center for Special Collections, University of Pennsylvania Libraries.

An invitation card for the Video Art exhibition sent to Video Hiroba member Morihiro Wada.

An invitation card for the Video Art exhibition sent to Morihiro Wada.

Exhibition catalog for the Video Art exhibition.

Letters between Suzanne Delahanty, curator of the Video Art exhibition and Fujiko Nakaya, representative for Video Hiroba.

©Constance Mensh

Works in the Gallery

Mako Idemitsu, Woman’s House, 1972. 16mm film transferred to digital video, 13:40 min, color, sound. Courtesy of the artist.

Mako Idemitsu, Women, 1977. Four-channel standard-definition video installation, approx. 18 min each, b/w, sound. Courtesy of the artist.

Shigeko Kubota, Video Girls and Video Songs for Navajo Sky, 1973. Standard-definition video, 31:56 min, b/w and color, sound. Courtesy of the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation and Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York.

Shigeko Kubota, excerpts from documentation of the Video Talk Show, 1977 (with Suzanne Delehanty and Gerald O'Leary, March 23, 1977; and David Ross, Barbara London, John Hanhardt, and Jonathan Price, December 18, 1977). Standard-definition video, b/w, sound. Courtesy of the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation.

Kyōko Michishita, Being Women in Japan: Liberation Within My Family, 1973–1974. Standard-definition video, 30 min, b/w, sound. Courtesy of the artist and V-Tape.

Fujiko Nakaya, Friends of Minamata Victims - Video Diary, 1972. Standard-definition video, 20 min, b/w, sound. Courtesy of the artist and the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum.

Related Resources

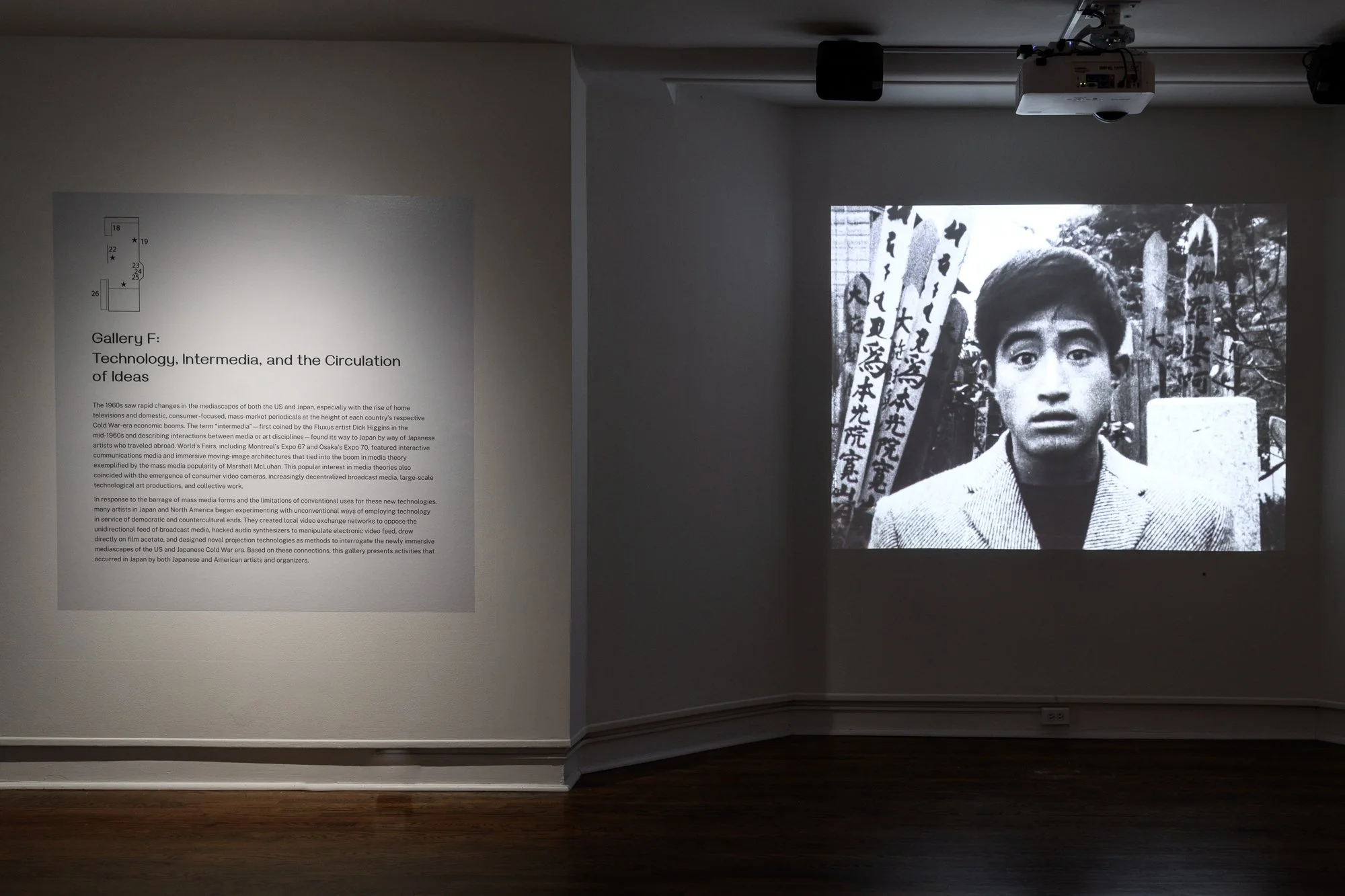

Gallery F

Photographs by Constance Mensh

The 1960s saw rapid changes in the mediascapes of both the US and Japan, especially with the rise of home televisions and domestic, consumer-focused, mass-market periodicals at the height of each country’s respective Cold War-era economic booms. The term “intermedia”—first coined by the Fluxus artist Dick Higgins in the mid-1960s and describing interactions between media or art disciplines—found its way to Japan by way of Japanese artists who traveled abroad. World’s Fairs, including Montreal’s Expo 67 and Osaka’s Expo ’70, featured interactive communications media and immersive moving-image architectures that tied into the boom in media theory exemplified by the mass media popularity of Marshall McLuhan. This popular interest in media theories also coincided with the emergence of consumer video cameras, increasingly decentralized broadcast media, large-scale technological art productions, and collective work.

In response to the barrage of mass media forms and the limitations of conventional uses for these new technologies, many artists in Japan and North America began experimenting with unconventional ways of employing technology in service of democratic and countercultural ends. They created local video exchange networks to oppose the unidirectional feed of broadcast media, hacked audio synthesizers to manipulate electronic video feed, drew directly on film acetate, and designed novel projection technologies as methods to interrogate the newly immersive mediascapes of the US and Japanese Cold War era.

DIY Technology & Kō Nakajima

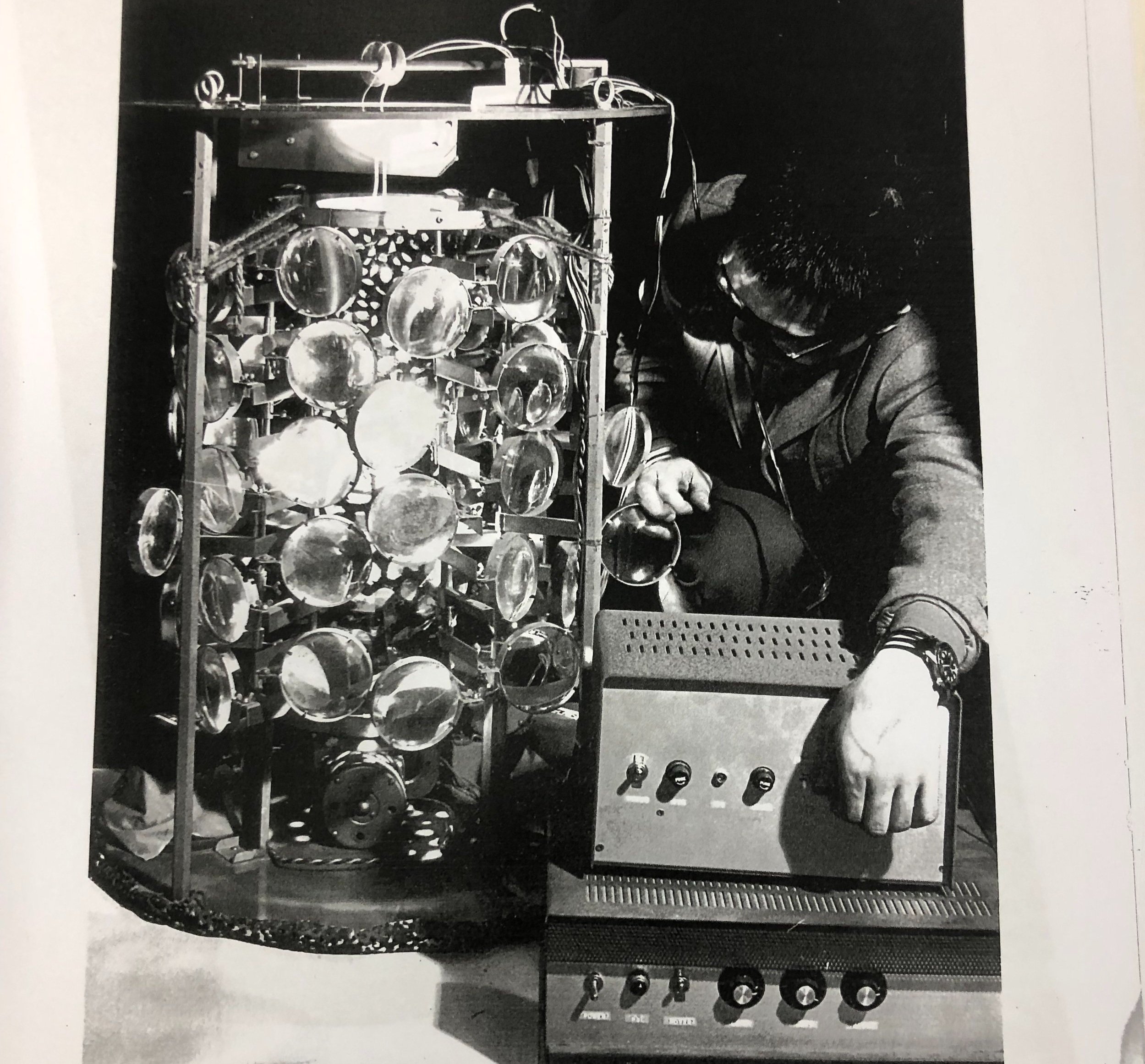

In the 1970s and 1980s, artists and technicians began to explore the outer reaches of what could be done with emerging electronic and moving-image technologies. One of Kō Nakajima’s (b. 1941) early DIY inventions was a “projector” made out of a glass disk that held water and colored oil inside. He presented one version, which included a fish floating in the disk, projected onto the wall “guerrilla” style (without seeking permission) during the Merce Cunningham company’s dress rehearsal at the Sōgetsu Art Center. Nakajima continued to explore this format of oil or water in glass tubes in his Shikotsuki (bone machine) projector. Experiments with image processing in video began in the late 1960s with Eric Siegel’s Process Chrominance Synthesizer (1968) and the popular and much-adapted Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer, first completed by Nam June Paik and Shuya Abe in 1970. The Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer debuted with Video Commune: The Beatles from Beginning to End on WGBX 44 and contributed to Paik's intermedia video-film collaborations with Jud Yalkut.

Nakajima participated in Montreal Expo 67 as a cameraperson for the film Human’s Hymn, directed by Kōzō Sasagawa, which won the silver medal. Nakajima visited the Expo, which appears in his documentation of the Osaka Expo ’70. Further information about Kō Nakajima’s work is available in his interview (linked below).

Ephemera and photographs related to Kō Nakajima. Courtesy of Kō Nakajima and the Keio University Art Center

Photograph of Kō Nakajima and Liquid Projector (Ryūdōtai Purojekutā), 1969. Photographer unknown.

Photograph of Kō Nakajima’s glass skeleton made for Shikotsuki (bone machine) projector, ca. 1969.

Photograph of Kō Nakajima’s glass skeleton piece.

Photograph of Kō Nakajima’s glass skeleton piece.

Leaflet for Ode of Life (1967), directed by Kōzō Sasagawa with camerawork by Kō Nakajima, produced for the Montréal International Film Festival at Canada’s Expo 67.

©Albert Yee

©Albert Yee

©Constance Mensh

Fujiko Nakaya and the Osaka Expo ’70

Fujiko Nakaya's trademark fog sculptures, first displayed at the Expo ’70s Pepsi Pavilion, manipulate atmospheric elements to produce dynamic, site-specific artworks. She was also heavily involved in organizing the participation of Japanese artists in what was to have been a series of performances in the Pepsi Pavilion throughout the run of Expo ’70. Although canceled due to budget overruns, the remaining proposals give us a sense of the breadth of intermedia experiments circa 1970. Prior to the founding of Video Hiroba, Nakaya helped facilitate E.A.T.’s research into video and screen technologies, apparently in relation to their Automation House and Anand Projects. Nakaya also founded the Tokyo branch of E.A.T. in 1971 in preparation for the Tokyo branch of Telex Q&A, which coordinated transcontinental conversations via telex between New York, Stockholm, Ahmedabad, and Tokyo over the course of a month as part of the Moderna Museet’s exhibition, Utopias & Visions 1871–1981.

Michael Goldberg and Video Hiroba’s Do-It-Yourself Kit exhibition

Video Hiroba was one of the first video collectives in Japan. It was formed on the occasion of the 1972 exhibition held in the Sony Building in Ginza entitled Video Communications: Do-It-Yourself Kit, in which Canadian video artist Michael Goldberg helped introduce the new Sony Portapak. Organized chiefly by Fujiko Nakaya and Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, original members included Hakudō Kobayashi, Miyai Rikurō, Matsumoto Toshio, Ichiyanagi Toshi, and Yoshiaki Tōno. Nobuhiro Kawanaka, Sakumi Hagiwara, Seiichi Fujii, Hara Eizaburō, and Nakahara Michitaka had also participated in the first exhibition and were listed as members by the time the group released its first self-published journal in September 1972. Membership was fluid, with other artists such as Kyōko Michishita and Morihiro Wada joining later and some, notably Mako Idemitsu, participating in group exhibitions without officially joining the collective.

The group organized exhibitions including Video Week: Open Retina Grab Your Image in October 1972; a collaborative event with US practitioners including a workshop and symposium; and Tokyo-New York Video Express at the Tenjō Sajiki Hall in January 1974, which Shigeko Kubota helped to coordinate. Alongside their exhibitions, Video Hiroba held video workshops, published a journal entitled Video Express, and rented out their collectively owned Sony Portapak cheaply to their own members.

Video Hiroba also produced work collectively, positioning video as an instrument for social change. In their 1973 project, Study of Participation Methods for New and Current Residents in Urban Development Planning, they collaborated with the city of Yokohama to experiment with mediating the relationship between citizens and local bureaucrats in the urban redevelopment of central Yokohama. Using video technology to collect and circulate citizens’ opinions on civic issues resulted in a previously unrecognized expression of the community’s underlying dissensus. Likewise, their Green Plaza PR Center project at Tōhoku Electric Power Company’s Niigata branch office used video as part of the process of designing a community space in lieu of a conventional PR Center, and incorporated a community-accessible video production studio into the final design. Video was seen by the group as a medium for altering the terms of social relations in the wake of the failures of the 1960s protest movements.

Processes of exchange were essential to the development of video. Both knowledge and equipment were shared between video practitioners in Japan and the US through events such as Video Communication: Do-It-Yourself-Kit at the Sony Building; Video Week: Open Retina Grab Your Image at the American Center, Tokyo; and Tokyo-New York Video Express, organized by Shigeko Kubota for Video Hiroba in Shūji Terayama’s Tenjō Sajiki’s basement theater. Video also facilitated exchange between individuals and groups: global exchanges of video letters were organized by Mits Kataoka and Hakudō Kobayashi, and the work of Video Hiroba in Japan and DCTV in New York amplified the voices of marginalized communities.

The three titles digitized from Michael Goldberg’s collection highlight selected performances presented as part of the Video Communications: Do-It-Yourself Kit event. Terrence Reid’s Coke in the Hole (1972) involved eighteen TV monitors and eighteen Coke bottles: A performer beneath the table reaches through a hole for a Coke bottle above the table, pouring its contents out into the second hole. With the first pouring, the first monitor turns on which and displays a Coke bottle emptying; all other Coke bottles are emptied and the monitors are turned on. The industrial mass production of Coke bottles is mirrored by the media’s endless replications. Terry Reid was assisted by Ritva Saarikko and Hakudō Kobayashi, with videography by Taiji Arita. Katsuhiro Yamaguchi’s EAT (1972) was performed during the DIY Kit exhibition. Yamaguchi and Hakudō Kobayashi took turns videotaping each other while the other ate. The documentation of the performance was displayed live on a monitor in the exhibition space. Seiichi Fujii’s performance, Kite captures Seiichi Fujii’s participation as a Video Hiroba member.

Photographs (facsimiles) of the Video Communications: Do-It-Yourself Kit exhibition, 1972. Courtesy of Michael Goldberg and Yūzō Tateishi.

Exhibition wall text at Video Communications: Do-It-Yourself Kit exhibition, 1972.

Visitors at the exhibition.

Michael Goldberg explains video delay start timing to Nobuhiro Kawanaka.

Video delay equipment.

Nobuhiro Kawanaka explains video delay installation.

Monitor wall at the exhibition.

Visitors at the exhibition.

Children viewing the video delay.

Video Week: Open Retina Grab Your Image, Video Picnic event organized by the American Center, 1972. Courtesy of Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, and the Mori Art Museum.

Photograph of Video Week: Open Retina Grab Your Image, Video Picnic, 1972.

Katsuhiro Yamaguchi and Arthur Ginsberg at Video Picnic.

Participants at Video Picnic.

©Constance Mensh

©Constance Mensh

Film Indépendent

Film Indépendent was a group for producing and screening independent and experimental films founded in 1964 by Masao Adachi, Takahiko Iimura, Nobuhiko Ōbayashi, Kenji Kanesaka, Jūshin Satō, Yōichi Takabayashi, Donald Richie, and others. This collective of independent filmmakers was primarily comprised of those who received a group award at EXPRMNTL 3 (1963) in Knokke-le-Zoute, Belgium. It is an early example of a collaboration between Japanese and American filmmakers. (Donald Richie, based in Japan at the time, was a film critic, historian, and filmmaker with a focus on Japanese cinema.) They also published a manifesto in Yomiuri Shimbun (Yomiuri Newspaper) about “free cinema that breaks away from capital and industrial filmmaking.” The group organized a one-off event titled A Commercial for Myself (December 16–17, 1964), but activities were infrequent thereafter.

A Commercial for Myself was a film program that presented personal films of the approximate duration of a TV commercial. Many Japanese artists, most of whom had never made a film before, were encouraged to try out filmmaking and Takahiko Iimura helped many of them out with their productions. Three filmmakers and their contributions to this screening are highlighted in this exhibition: Yasunao Tone, who moved to the United States in 1972, made 2,880K=120”, which involves a close-up of a ticking stopwatch; Donald Richie shot Jinsei, which depicts a man’s lifetime in three minutes, with Richie’s own singing of the soundtrack accompanying the slapstick humor of the film; and Mary Evans, an American writer and Richie’s then-wife, made Gomi, which stars Richie and is playful take on parenting set in a dumpster yard.

©Albert Yee

©Constance Mensh

The American Center Japan and Cross Talk / Intermedia

Cross Talk was a multiyear event series co-organized by American composers Karen Reynolds and Roger Reynolds with Japanese composers Kuniharu Akiyama and Jōji Yuasa through the American Cultural Center to showcase contemporary music from Japan and the US in a kind of exchange. After three music-focused concerts in 1967 and 1968, the group organized a three-day festival in February 1969 entitled Cross Talk / Intermedia thatpresented the latest in cross-genre experiments. Sponsored by Pepsi and held in a gymnasium designed by Kenzō Tange for the 1964 Summer Olympics, the free event brought intermedia into the mainstream. In similar fashion to Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.)’s 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering (1966), Cross Talk / Intermedia was ambitious in its scope. It was supported by electronic companies Sony, Pioneer, and TEAC Corporation through loans and assistance in inventing equipment for use in several performances. The resulting event involved a series of large-scale presentations, including projections onto large inflatables such as Projection for Icon (Icon no tame no projection, 1969) by Toshio Matsumoto or Circles (1969) made by Takahiko Iimura in collaboration with musician Alvin Lucier. In just two years, the scale of the locations in which intermedia was presented moved from the small confines of a gallery to a sports gymnasium.

Ephemera and photographs (facsimiles) related to Cross Talk / Intermedia, 1969. Courtesy of Roger and Karen Reynolds and private collection.

From left to right: Jōji Yuasa, Gordon Mumma, and Roger Reynolds.

Rehearsal view.

Roger Reynolds performing Erik Satie’s Vexations.

Roger Reynolds conducting Salvatore Martirano’s Ballad.

Tōru Takemitsu and Roger Reynolds.

Toshio Matsumoto’s rehearsal.

From left to right: Gordon Mumma, Roger Reynolds, Toshi Ichiyanagi, Kuniharu Akiyama, and Jōji Yuasa.

Toshio Matsumoto’s rehearsal.

From left to right: Roger Reynolds, Tōru Takemitsu, and Jōji Yuasa at Reynolds’ residence in Del Mar, San Diego.

Jūnosuke Okuyama.

Jōji Yuasa and Roger Reynolds.

Opening night at Yoyogi Stadium.

Opening night at Yoyogi Stadium.

Karen Reynolds performing Robert Ashley’s That Morning Thing.

Program notes and essays.

©Constance Mensh

©Constance Mensh

©Constance Mensh

Works in the Gallery

Kō Nakajima, Liquid Projector (Ryūdōtai Purojekutā), 1969/2024. Wood, aluminum, acrylic, glass, motors, LED lamp, and 16mm film.

Kō Nakajima, documentation of Osaka Expo ’70, 1970. 16mm film transferred to digital video, 11:40 min, b/w, silent. Courtesy of Kō Nakajima and the Keio University Art Center.

Performance documentation of Terrence Reid, Coke in the Hole, 1972. Standard-definition video, 8:29 min, b/w, silent. Video by Taiji Arita. Courtesy of the artist and Michael Goldberg.

Yamaguchi Katsuhiro, EAT, 1972. Standard-definition video, 10:01 min, b/w, sound. Video by Hakudō Kobayashi. Courtesy of the artist and Michael Goldberg.

Performance documentation of Seiichi Fujii, Kite, 1972. Standard-definition video, 4:55 min, b/w, sound. Video by Michael Goldberg. Courtesy of the artist and Michael Goldberg.

Donald Richie, Jinsei [life], 1964. 16mm transferred to digital video, 2:40 min, b/w, sound. Collection of Takahiko Iimura.

Mary Evans, Gomi [trash], 1964. 16mm transferred to digital video, 2 min, b/w, sound. Collection of Takahiko Iimura.

Yasunao Tone, 2,880K=120”, 1964. 16mm transferred to digital video, 3 min, b/w, silent. Collection of Takahiko Iimura.

Related Resources

Closet

Photographs by Constance Mensh

Dead Movie was Takahiko Iimura’s film installation—the first of many—to take the medium of film as its main subject using a minimalist set-up. The installation involves two projectors facing one another: one projector projects black 16mm film leader looped through a hook on a ceiling; the second projector, facing the other one, projects only light with no film running through it, thereby casting a shadow of the projector and the film against the opposite wall. The work was first presented at the Judson Gallery, located in the basement of Judson Church, in 1968. In 1971, Iimura presented Dead Movie as part of the fifth Japan-Germany Contemporary Music Festival, which took place at the Goethe Institute, Tokyo, alongside music recitals and dance performances staged simultaneously in the form of a “wandering concert.” At this event, Iimura staged a performance with his installation by cutting holes out of the black film leader using a hole-puncher—a gesture that harks back to his earlier film On Eye Rape (1962), performative iterations of Onan (1963), and the expanded cinema performance Floating (1970), and to which he returns in his performance Circle and Square (1981).

Works in the Gallery

Takahiko Iimura, Dead Movie, 1968/2024. Two 16mm film projectors and 16mm black leader film.

Checklist

Archival presentation of Takahiko Iimura and Alvin Lucier, Shelter 9999, 1966–1968. Three projections and stereo sound comprising thirty-one color slides (looped); 16mm film transferred to digital video, 28:09 min, looped; three 16mm films transferred to digital, 9:28 min (total), looped; and stereo sound, 32:42 min, looped. Collections of Akiko and Takahiko Iimura, and Alvin Lucier papers, 1939–2015, New York Public Library Archives. Courtesy of the artists.

Akiko Iimura, Mon Petit Album, 1974. 16mm film transferred to digital video, 12 min, color, sound. Collection of the artist.

Takahiko Iimura, Taka and Ako, 1966. 16mm transferred to digital video, 13 min, b/w, silent. Collection of the artist.

Archival presentation of Dream Reel, a mixed media performance in Isobe’s Floating Theater, originally presented at State University at Oneonta, March 23, 1969. Parachute and 16mm film transferred to digital video. Courtesy of Yukihisa Isobe, the Jud Yalkut Estate, and Anthology Film Archives.

Film documentation of Yukihisa Isobe’s work by Jud Yalkut. 16mm film transferred to digital video. Courtesy of Jud Yalkut Estate and Anthology Film Archives.

Takehisa Kosugi, TM, 1974. 16mm film transferred to digital video, 3 min, color, silent. Courtesy of the Estate of Takehisa Kosugi

Seiichi Fujii, Body Wave, 1970. 16mm film transferred to digital video, double projection, 35 min, b/w and color, sound. Courtesy of the artist.

Kenji Kanesaka, Super Up, 1966. 16mm transferred to digital video, 13 min, color, sound. Courtesy of the artist and the Chicago Film Archives.

Masanori Ōe and Marvin Fishman, Great Society, 1967. Six projection 16mm film transferred to digital video, 17 min, color, sound. Courtesy of the artist and S.I.G.

Masanori Ōe, Head Game, 1967. Film transferred to digital video, 10 min, color, sound. Courtesy of the artist and S.I.G.

Masanori Ōe, No Game, 1967. Film transferred to digital video, 17 min, b/w, sound. Courtesy of the artist and S.I.G.

Mako Idemitsu, Woman’s House, 1972. 16mm film transferred to digital video, 13:40 min, color, sound. Courtesy of the artist.

Mako Idemitsu, Women, 1977. Four-channel standard-definition video installation, approx. 18 min each, b/w, sound. Courtesy of the artist.

Shigeko Kubota, Video Girls and Video Songs for Navajo Sky, 1973. Standard-definition video, 31:56 min, b/w and color, sound. Courtesy of the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation and Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York.

Shigeko Kubota, excerpts from documentation of the Video Talk Show, 1977 (with Suzanne Delehanty and Gerald O'Leary, March 23, 1977; and David Ross, Barbara London, John Hanhardt, and Jonathan Price, December 18, 1977). Standard-definition video, b/w, sound. Courtesy of the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation.

Kyōko Michishita, Being Women in Japan: Liberation Within My Family, 1973–1974. Standard-definition video, 30 min, b/w, sound. Courtesy of the artist and V-Tape.

Fujiko Nakaya, Friends of Minamata Victims - Video Diary, 1972. Standard-definition video, 20 min, b/w, sound. Courtesy of the artist and the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum.

Kō Nakajima, Liquid Projector (Ryūdōtai Purojekutā), 1969/2024. Wood, aluminum, acrylic, glass, motors, LED lamp, and 16mm film.

Kō Nakajima, documentation of Osaka Expo ’70, 1970. 16mm film transferred to digital video, 11:40 min, b/w, silent. Courtesy of Kō Nakajima and the Keio University Art Center.

Performance documentation of Terrence Reid, Coke in the Hole, 1972. Standard-definition video, 8:29 min, b/w, silent. Video by Taiji Arita. Courtesy of the artist and Michael Goldberg.

Yamaguchi Katsuhiro, EAT, 1972. Standard-definition video, 10:01 min, b/w, sound. Video by Hakudō Kobayashi. Courtesy of the artist and Michael Goldberg.

Performance documentation of Seiichi Fujii, Kite, 1972. Standard-definition video, 4:55 min, b/w, sound. Video by Michael Goldberg. Courtesy of the artist and Michael Goldberg.

Donald Richie, Jinsei [life], 1964. 16mm transferred to digital video, 2:40 min, b/w, sound. Collection of Takahiko Iimura.

Mary Evans, Gomi [trash], 1964. 16mm transferred to digital video, 2 min, b/w, sound. Collection of Takahiko Iimura.

Yasunao Tone, 2,880K=120”, 1964. 16mm transferred to digital video, 3 min, b/w, silent. Collection of Takahiko Iimura.

Takahiko Iimura, Dead Movie, 1968/2024. Two 16mm film projectors and 16mm black leader film.

Events

See here for the complete list of events in this project, including online screenings.

Apr 20, 2024: Immigrant Artists Exchange: Discussing the Locality, in Partnership with Japan America Society of Greater Philadlephia (JASGP) and Fleisher Art Memorial

Jun 4, 2024: The Curfew Lookbook: A screening with Shehrezad Maher, in Partnership with Twelve Gates Arts

Jun 15, 2024: A Talk on the Video Talk Show: A Panel Discussion, in Partnership with Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation

Jun 16, 2024: Films & Yasunao Tone: Composer, Filmmaker, and Performer

Jun 16, 2024: Magnetic Resonances: Japanese and American artists in the 1975 ICA Video Art exhibition

Jun 17, 2024: Symposium: Community of Images, in Partnership with JASGP and University of Pennsylvania, East Asian Languages & Civilizations

Jun 22, 2024: Family Program - Vintage Vanguard: Experimental Art Workshop

Jul 31, 2024 – Aug 1, 2024: PhillyCAM Youth Media Workshop x Community of Images

Aug 1, 2024: Video Letter Exchange at Asia Art Archive in America

Aug 9, 2024: Closing Reception & Performance Featuring Kuroshio (Jason Finkelman, Joy Yang & Geoff Gersh), Aaron Pond Trio, and DuiJi

Sep 28, 2024: Video Letter Exchange - Screening & Performance, in Partnership with CineSpeak, JASGP, and Asian Arts Initiative

©Erin Blewett

DÔME DO, WE--After Yukihisa Isobe's Air Dome (1970)

Photographs by Erin Blewett and Ann Adachi-Tasch

As part of the Community of Images exhibition, we are pleased to invite artist and urban planner Yukihisa Isobe to revisit his connection to Philadelphia and New York City of the 1960s and ‘70s. The forthcoming project will reflect on Isobe’s innovative and socially-engaged work. Grounded by his artistic practice and experiences as a postgraduate student at The University of Pennsylvania, Isobe worked with organizations including the NYC Dept. of Parks & Recreation and The Phoenix House (a drug and alcohol rehabilitation facility). In 1970 Isobe presented a large-scale inflatable artwork titled Air Dome to mark the first Earth Day celebration at New York City’s Union Square.

In the 2024 interpretation of Air Dome, Philadelphia artist Aaron Igler will lead the design and programming of a community-built dome structure titled DÔME DO.WE (a space for reset). The project was conceived as a site for collaborative skillshare, small group dialog, a lecture program, sonic performances, film screening, and more.

Sited within the monumental Sycamore grove of Eakins Oval on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway and rooted in the concept of mutually-supporting systems, DÔME DO.WE (a space for reset) will investigate geodetic models as they relate to Isobe’s work, contextualized by his creative influences including the pioneering landscape architect Ian McHarg (UPenn) and the architect/futurist Buckminster Fuller, who each developed groundbreaking ideas focused on humans relational role within built and biological environments as a way of better understanding, managing, and preserving the earth.

DÔME DO.WE (a space for reset) is planned to be built and activated with the assistance of community participants, foregrounding a design/build process and creative engagement as fundamental goals, continuing Philadelphia history as a center for creative thinking and artistic community.

Preservation Outcomes

Our core mission, preservation, was the main goal in the project. The following works and materials were digitized, reconstructed, or preserved, and they are in the process of finding permanent archival homes.

Seiichi Fujii, Body Wave, 1970, 16mm film transferred to digital video, double projection, 35 min, b/w and color, sound.

Takahiko Iimura, Shelter 9999, 1966–1968, thirty-one color slides transferred to digital. (Takahiko Iimura collection)

Takaiko Iimura, photographs, digitized. (Takahiko Iimura collection)

Takahiko Iimura, Shelter 9999, 16mm film transferred to digital video, 28:09 min. (Takahiko Iimura collection)

Takahiko Iimura, Shelter 9999, three 16mm films transferred to digital, 9:28 min total. (Alvin Lucier Papers at the New York Public Library)

Shigeko Kubota, Video Talk Show, 1977 (with Suzanne Delehanty and Gerald O'Leary, March 23, 1977; and David Ross, Barbara London, John Hanhardt, and Jonathan Price, December 18, 1977). Standard-definition video, b/w, sound. Courtesy of the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation.

Shigeko Kubota, Confession, Janice (#144), Standard-definition video

Shigeko Kubota, Norie, Garden Satellite for Window (#257), 1976

Michael Goldberg, Reel 1 "Seiichi Fujii" and "Ichiro Hagiwara" 01:00 - 17:58 (the Kite performance)

Michael Goldberg, Reel 2 "Tokyo Kid Brothers"

Michael Goldberg, Reel 3 "Dabu Dabo" and "Gann (Tetsuo) Matsushita"

Michael Goldberg, Reel 4 "Terry Reid" + Katsuhiro Yamaguchi's EAT performance

Michael Goldberg, Reel 5 "Seiichi Fujii" and "Takamichi Sugiyama" 22:58

Ko Nakajima, Liquid Projector (Ryūdōtai Purojekutā), 1969 [2024 reconstruction]

Ko Nakajima, Documentation of Osaka Expo ’70, 1970, 16mm film transferred to digital video

Ko Nakajima, Mao Zedong, 16mm film transferred to digital video

Ko Nakajima, Shadow, 16mm film transferred to digital video

Ko Nakajima, Photograph of Shikotsuki Object

Reviews

AsiaArtPacific, By Leah Triplett Harrington

Community of Images: Japanese Moving Image Artists in the US, 1960s–1970s

August 12, 2024

The Wire, By Joshua Minsoo Kim

On Site

November 2024 (Issue 489)

Afterimage, By Helena Shaskevich

December 2024 (forthcoming)