Essay: Japanese Street Vids and Public Access Television (Antoine Haywood)

Antoine Haywood, PhD candidate at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School for Communication, on the CATV projects of collective Video Earth.

Japanese Street Vids and Public Access Television: Unseen Gems Excavated and Preserved in the Video Earth Digital Archive

By Antoine Haywood

Antoine Haywood is a PhD candidate and Penn Presidential Fellow at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School for Communication. His research focuses on local storytelling networks and understanding the contemporary relevance of community access media. Before Annenberg, Antoine spent fifteen years working as a community engagement director in the PEG access media field.

This text was published as an introduction to our 2023 September Members’ Viewing program, which included three works from Video Earth: Early Work of Video Earth: Izu Shimoda CATV/ Hokkaido Ikeda CATV (1971), A Graveyard and a Beggar (1975), and Under A Bridge (1974).

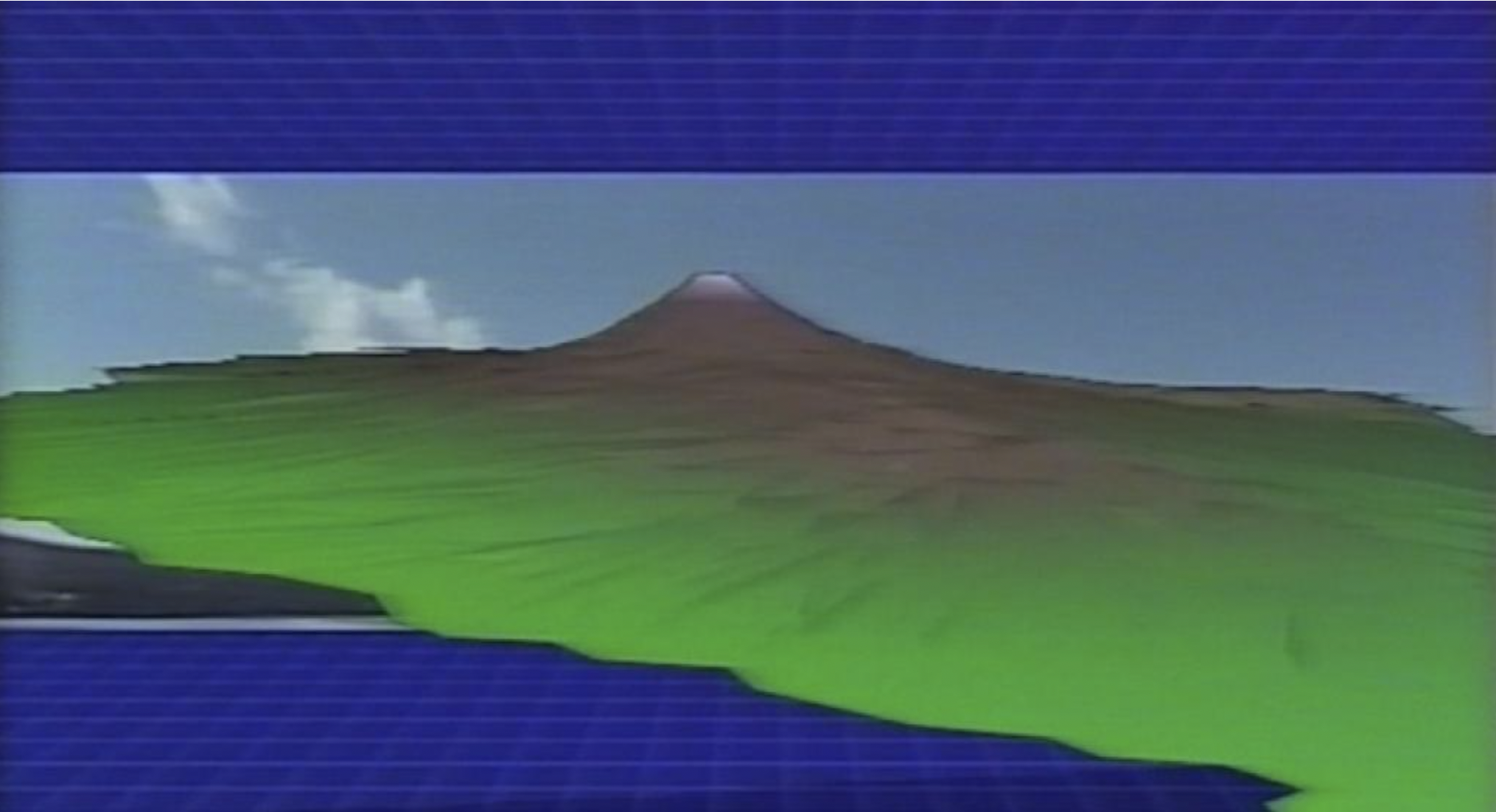

Ko Nakajima & Video Earth, Early Work of Video Earth: Izu Shimoda CATV/ Hokkaido Ikeda CATV (1971) ©Ko Nakajima

Founded in 1971, Video Earth was part of the first generation of Japanese video art collectives that used emergent televisual technology to oppose previous generations' artistic traditions.[i] Other notable collectives launched during this period include Video Hiroba, formed in March 1972, and the Video Information Center, founded by Ichiro Tezuka in 1974. Distinct from its contemporaries, Video Earth was initially formed by Ko Nakajima to “unite people interested in public-access cable television” and “heighten viewers’ awareness of ecological dilemmas.”[ii] While much attention has been given to Nakajima’s influential animation films, art installations, and time-lapse video experiments, this essay sheds light on the significance of the street-level perspective videos that Nakajima’s collective created in the 1970s. “A Graveyard and Beggar,” “Under A Bridge,” and “Early Work of Video Earth: Izu Shimota CATV / Hokkaido Ikeda CATV” are striking reflections of what media historian Deirdre Boyle described as the “larger alternative media tide” that swept through the United States and many other countries in the 1960s and ‘70s.[iii]

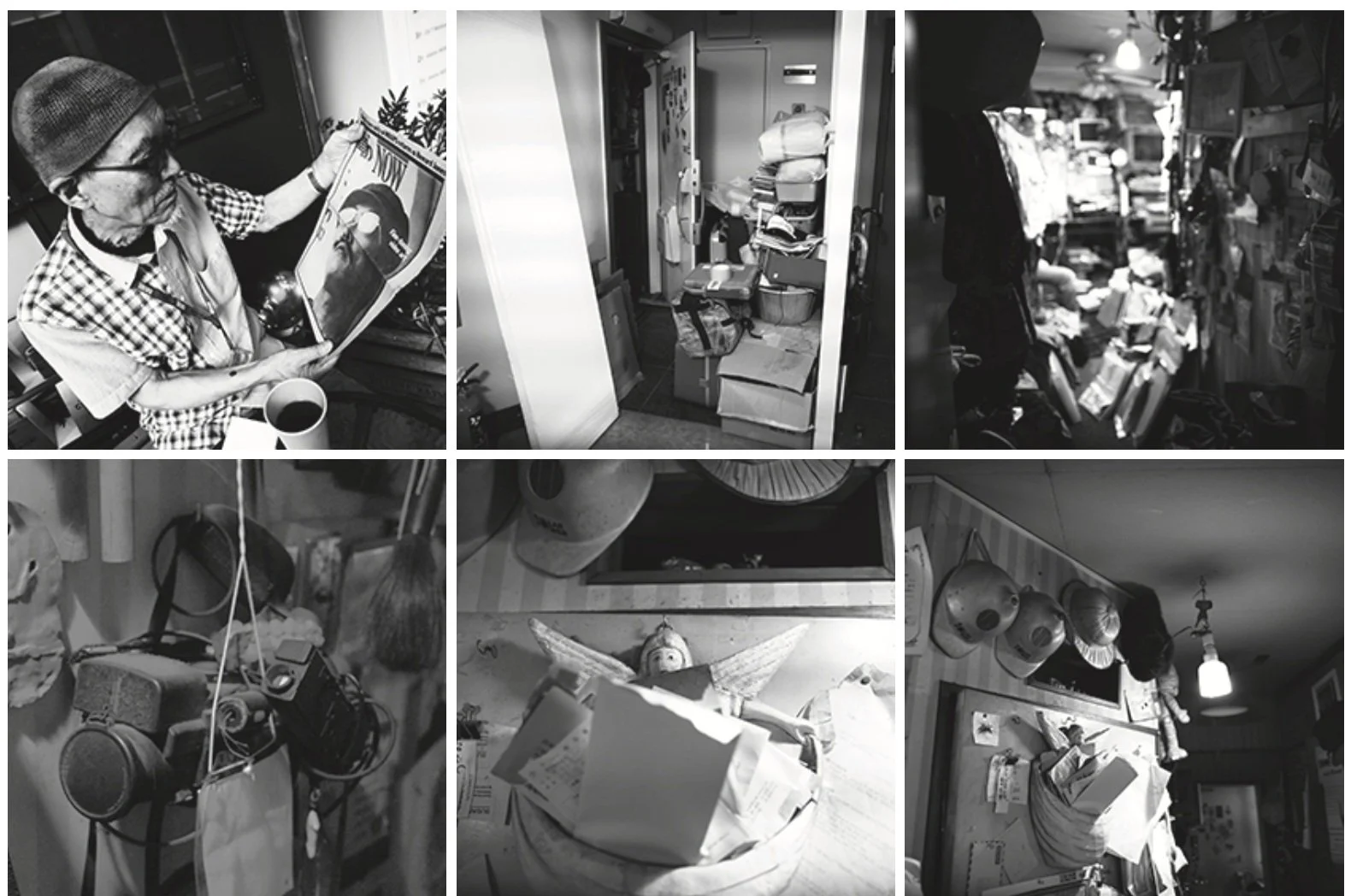

Unlike traditional journalists, Video Earth members used unorthodox methods to capture the authentic qualities of the communities they explored. They did not use video to create scripted stories and formulaic news reports. Instead, they made themselves vulnerable to the fate of their interactions, which, as seen in “A Graveyard and Beggar” and “Under A Bridge,” was a perilous choice. The Video Earth members that boldly approached strangers were clearly unwelcome. Both interviewees firmly opposed the invasion of their privacy, which raises ethical considerations about this cinéma-vérité style of documenting human experiences. Nonetheless, the interviewers’ tenacious ability to establish a rapport with their interlocutors demonstrated an impressive process-oriented technique. While the woman who lived at Aoyama cemetery never let her guard down, besides cracking a few smiles and sarcastic remarks, the man under the bridge opened up and recounted life stories. Like geologists searching for gems in geodes, the Video Earth members used the portable video camera as a tool to find humanity sparkling in unexpected places.

“I don’t want to talk with you.” The subjects of Under the Bridge (left) and A Graveyard and a Beggar (right). ©Ko Nakajima

In the mid-1960s, Japan’s Sony Corporation introduced the portapak—a groundbreaking portable camera and half-inch videotape recording system that allowed collectives like Video Earth to rove and produce vérité-style videos, as seen in “A Graveyard and Beggar” and “Under A Bridge.” The unconventional documentary approach Video Earth used resembles the so-called “guerrilla video” methodology that was also being practiced in North America during this period. The Canadian Challenge for Change program, the New York-based Downtown Community Television (DCTV), and other guerrilla video collectives, like the Videofreex, Top Value Television (TVTV), Global Village, and the Raindance Corporation, were made up of vanguard media makers who used 16-millimeter Bolex film cameras and video portapaks to capture authentic perspectives of life lived on a neighborhood community level.

Like Video Earth, Keiko Tsuno, the Japanese-born co-founder of DCTV, also started creating short ethnographic shorts and a “series of video poems” during this period.[iv] Tsuno began experimenting with video shortly after she graduated from art school in Japan, moved from Tokyo to New York City, and met her life partner and co-founder of DCTV, Jon Alpert. Tsuno was particularly drawn to video because of its unique properties. Unlike film, which required a processing wait time before viewing, video could be immediately played back and relayed to a television monitor (as Nakajima demonstrated in Video Earth’s CATV documentary). Tsuno also believed video rendered a unique softness resembling reality and provided undefined artistic exploration potential.[v] After saving the money she earned while waiting tables in a Japanese restaurant, Tsuno had her mother purchase a Sony portapak and ship it directly from Tokyo to the U.S. In 1972, Tsuno and Alpert founded DCTV to teach their neighbors how to use video as a community organizing tool. They realized community-made videos and public screenings were a powerful way for people to tell their own stories in ways that major broadcast networks did not.

Although there is little evidence of specific, formal ties between Video Earth and DCTV, there was a healthy transnational, cross-cultural exchange between Canadian video activist Michael Goldberg, who participated in a video communication residency in Japan. Goldberg’s influential “Video Communication Do-it-Yourself Kit,” an exhibit sponsored by Sony in Tokyo, attracted the attention of Japanese artists like Katsuhiro Yamaguchi and Fujiko Nakaya. Inspired by Goldberg’s teachings, a cadre of Japanese artists formed Video Hiroba (literally, “video plaza”), which followed a mission that reflected Michael Schamberg’s and the Raindance Corporation’s vision to transform consumer (video) technology into a politicized alternative media.[vi] According to Nakaya, Raindance Corporation's journal, Radical Software, which Schamberg distributed while visiting Tokyo in September 1971, significantly influenced the ideas and methods that defined Video Hiroba’s work.[vii] It was Video Hiroba’s founding members Fujiko Nakaya and Nobuhiro Kawanaka who, in 1974, made a Japanese translation of Shamberg's influential book Guerilla Television. While collaborative spirits, progressive ideologies, and portable video systems propelled groups like Video Hiroba and Video Earth, cable television also emerged in the 1970s as a new, locally accessible communication mechanism that allowed communities to distribute alternative media content.

Starting in the 1940s, tech-savvy individuals developed what was initially called “community antenna television” (CATV) in remote locations where broadcast signal reception was weak or entirely obstructed. These ad hoc systems drew from “an eclectic combination of makeshift technologies that captured broadcast signals from high places (such as mountaintops) and transmitted them to television sets in lower elevations.”[viii] In the 1950s and ‘60s, these CATV systems were primarily used to improve the reception of network broadcast signals. In this period, Japanese television was developed as “open-air television”—a novel marketing ploy implemented by the first commercial TV station, Nihon Terebi, also known as “NTV.”[ix] NTV strategically placed televisions in public places like railway stations, parks, and plazas to instill in working-class people the “desire to buy their own television sets, while simultaneously boosting the station’s advertising revenue.”[x] Another influential network that emerged during this time was the Japanese public broadcasting corporation—NHK. Early on, commercial networks and state agencies controlled what was televised over the national airwaves (mostly in industrialized countries). However, by the 1970s, artists, activists, and NGOs (non-government organizations) in various countries began tapping into closed-circuit cabling systems to leverage local communication infrastructure as an alternative to corporate media dominance.[xi] Video Earth’s tour of Izu Shimota, Hokkaido Ikeda, and Iida CATV stations captures this revolutionary communication phenomenon coming to life in Japan.

“What about the stuff from this station?” “It doesn’t play on my television.” An interviewee in Shimoda in the opening scene of Early Work of Video Earth: Izu Shimoda CATV/ Hokkaido Ikeda CATV ©Ko Nakajima.

The opening scene of “Izu Shimota CATV / Hokkaido Ikeda CATV” immediately conveys a long-term community-access television problem: lack of awareness. For decades, community access practitioners have faced questions about audience engagement and what matters most to practitioners. Is it the process or product of community television that influences change? One of the station managers was even asked how they get people to watch, especially those audiences captured by commercial broadcasting’s allure.

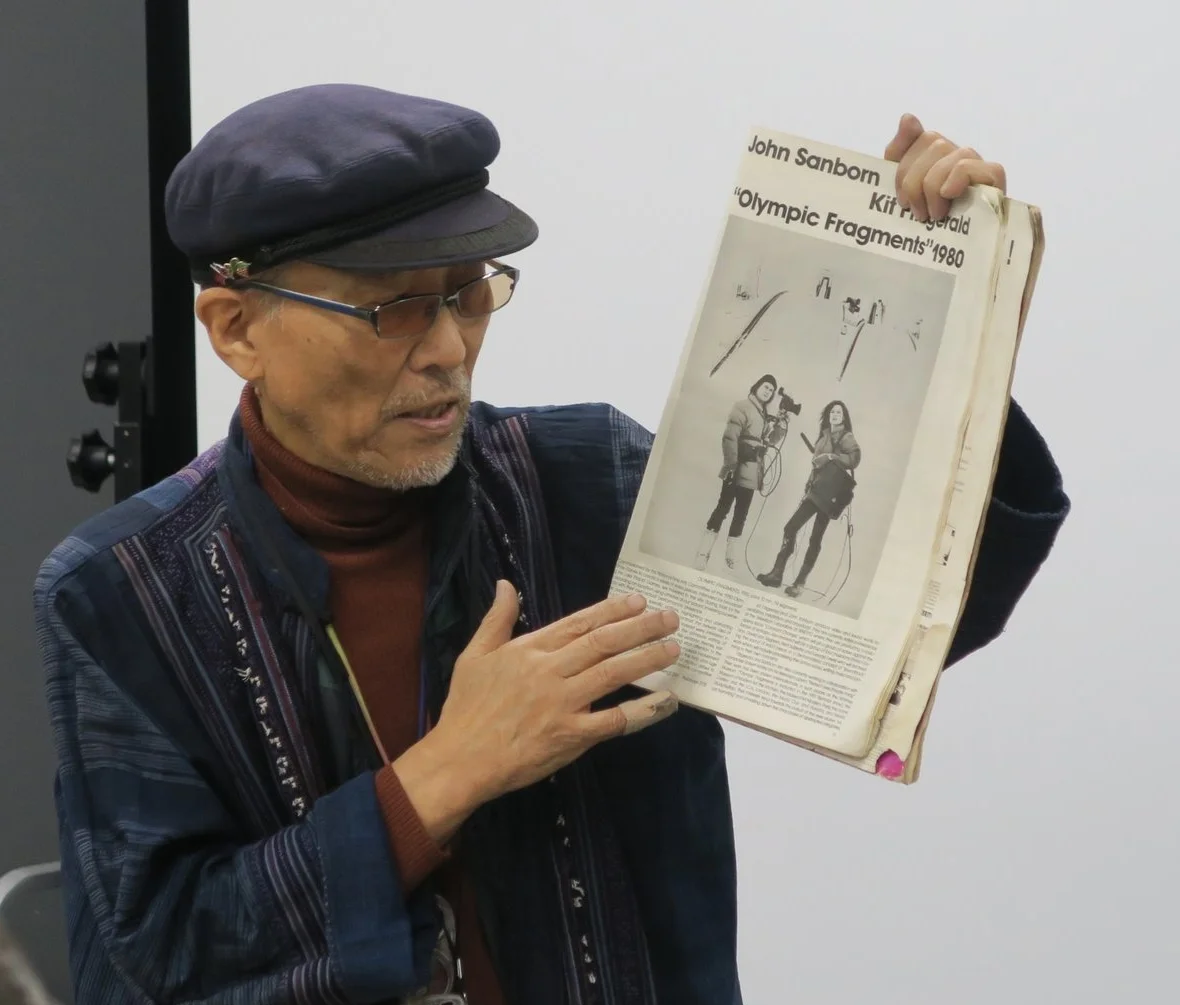

In contrast to “A Graveyard and Beggar” and “Under A Bridge,” the CATV piece is intentionally edited to juxtapose the perspectives of community television proponents and individuals in the community who are just being introduced to it. Most of the subjects interviewed were willing to express themselves on camera. Even the media students attending the special event appeared amicable and responsive to Ko Nakajima’s extemporaneous interview style. The inserted clips of community-made videos were excellent examples of how CATV channels provide programming that stands out from commercial media. As one person mentioned, people on professional networks are “robots.” These community clips ultimately illustrate CATV’s humanness and what one station manager described as “a gallery showcasing people’s passion.”

While the station managers expressed much optimism, the challenges of building and operating community-access television channels were quite apparent. Failing equipment, limited staff resources, and precarious relationships with local governments are issues that unfortunately still exist today, particularly in the United States, where community media centers that operate local access channels struggle to maintain their relevance in the digital age. Nonetheless, Video Earth’s CATV station tour video illuminates community-access television’s lasting potential as a resource that communities can use to cultivate what one interviewee called “video culture.” Although many operations that showed promise in the 1970s and ‘80s have since closed, thousands still exist worldwide. For example, in the U.S., 1600 local access television centers currently operate 3000 channels that feature community-made public, educational, and governmental (PEG) programming.[xii] Recent studies have shown that these community cable channels provide essential communication services, especially in crisis moments when residents need neighborhood-level information, perspectives, and connectivity.[xiii] As community television has demonstrated in the past and present, there will always be a need for grassroots communication infrastructures that public schools and local groups like civic and agricultural associations can use to disseminate timely information in places not directly served by national broadcast networks.

“I want to use my resources to put the spotlight on people who usually are not in the spotlight.” A CATV producer speaks about his aims in Early Work of Video Earth: Izu Shimoda CATV/ Hokkaido Ikeda CATV ©Ko Nakajima.

The Video Earth Collective work archived in Nakajima’s collection is an excellent glimpse of how Japanese visionaries were involved in the 1970s global alternative media tide—a phenomenon shaped by the convergence of portable video, cable television, and a progressive ethos. This inspired a new wave of alternative media makers determined to promote humanity and advance progressive social change. The television producer, interviewed at the end of the CATV video, articulated the community access television movement’s purpose best: “At this point, I want to use my resources to put the spotlight on people who usually are not in the spotlight. Just to let the world know, there are all these people, you know, living among us.” Media-making methodologies practiced by groups like Video Earth are essential subjects to remember and study because they remind us of how communication technology can be used to promote humanity genuinely.

[ii] London, Barbara. 1992. “Electronic Explorations.” Art in America, May 1992. 120-129.

[iii] Boyle, Deirdre. 1997. Subject to Change: Guerrilla Television Revisited (New York: Oxford University Press), xiii.

[iv] Hoberman, J. 1981. “Jon Alpert’s Video Journalism: Talking to the People.” American Film. June 1981, 58.

[v] Anderson, Joel Neville. 2017. “(Community) video art: DCTV’s expanded documentary practice.” Millennium Film Journal 65 (1).

[vi] Hiro, Rika. 2010. “Between Absence and Presence: Exploring Video Earth’s What is Photography?” Spectacle East Asia 15.

[vii] Meigh-Andrews 2014, 41.

[viii] Mullen, Megan. 2007. “The Moms ‘n’ Pops of CATV.” In Cable Visions: Television Beyond Broadcasting. Edited by Sarah Banet-Weiser, Cynthia Chris, and Anthony Freitas, 25-43. New York, NY: New York University Press.

[ix] Yoshimi, Shunya. 2005. “Japanese Television: Early Development and Research.” In A Companion to Television. Edited by Janet Wasko, 540-556. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

[x] Ibid. 540.

[xi] Halleck, DeeDee. 2005. “Local Community Channels: Alternatives to Corporate Media Dominance.” In A Companion to Television. Edited by Janet Wasko, 489-499. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

[xii] Alliance for Community Media. n.d. https://www.allcommunitymedia.org/

[xiii] Aufderheide, Patricia, Antoine Haywood, and Marian Sanchez Santos. 2020. “Public, Educational, and Governmental Access Media: Providing Contactless Community in a Pandemic.” Social Science Research Council, October 1, 2020, https://items.ssrc.org/covid-19-and-the-social-sciences/mediated-crisis/public-educational-and-governmental-access-media-providing-contactless-community-in-a-pandemic/