Community of Images: Dan sandin & ko nakajima

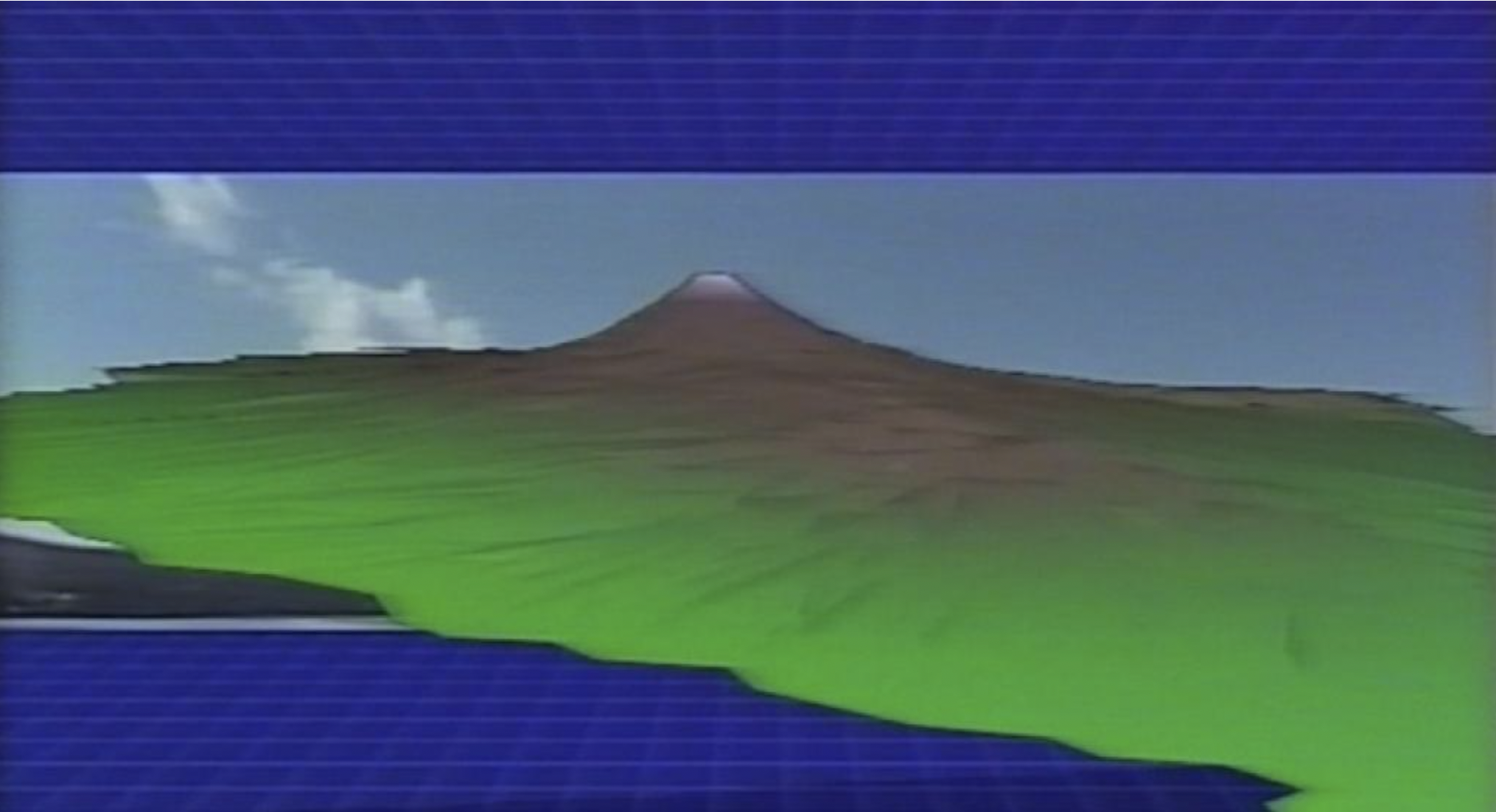

From Ko Nakajima, Mt. Fuji・富士山, 1984, 7 min

This December and January, as part of our Community of Images programming, CCJ are thrilled to present a two-month focus on the image-processing experiments of Ko Nakajima, particularly in relation to his time in the United States and Canada.

In December, we are proud to present two works by pioneering US artist-technician Dan Sandin (and his collaborators), generously lent by the artist himself, alongside the 10-minute version of Nakajima's iconic Mt Fuji (1984), a rhythmic meditation on nature, spirituality, and perspective which took influence from the groundbreaking Sandin Image Processor. Nakajima would later develop his own CG animation device, the Aniputer, a user-friendly image processing device developed with JVC which would later take on its own life among a younger generation of artists and technicians.

This program is in part made possible by Keio University Art Center and its project, Support Program to Promote Archives of Media Arts 2023: Digitizing and Cataloging of Performance and Exhibition Video Records from the post-1970s.

Our Community of Images programming is also generously supported by Pew Center for Arts and Heritage & the Andy Warhol Foundation.

We also thank scholar Nina Horisaki-Christens for her advice and consultation on the program.

PROGRAM

Ko Nakajima, Mt Fuji ・富士山, 1984, 7 min

Dan Sandin, Wandawega Waters, 1979, 9 min

Dan Sandin, Phil Morton, Tom DeFanti, Rylin Harris, Sticks Raboin, Bob Snyder, Jane Veeder, Mimi Shevitz, Raul Zaritsky and Jim Morissette. Compilation featuring demonstrations, performances and Spiral 1 (1975), Spiral 3, Spiral 5 PTL (1979) (more details below). 12 min

Become a member for just $5 a month to access our monthly programs, and share your thoughts on our screenings with us via Twitter, Instagram or Letterboxd.

the programs will be available for viewing on cCJ’s viewing platform.

This Members Viewing program is supported, in part, by a grant from the Toshiba International Foundation.

program

Ko Nakajima, Mt Fuji・富士山, 1984, 7 min version

Mt Fuji constructs a dynamic computer-collage out of a collection of photographs of the famous mountain, taken by Kozan Saito. Accompanied by music by Tsutomu Yamashita, the work creates endless iterations of its subject matter in a rhythmic exploration of representation, landscape, and digital space. Nakajima used computer animation in a number of films about nature with spiritual/Taoist themes, including Dolmen (1987), Rangitoto (1988), and Esprits de Sel (1990).

Dan Sandin, Wandawega Waters, 1979, 9 min

The Sandin family vacation home on Lake Wandawega in Wisconsin, videotaped in one day.

It was an early work created with the ‘digital image colorizer,’ a digital module that formed part of the analog Image Processor. It has been described by media scholar Bruce Jenkins as “an almost Blakean meditation on the cosmos that shifts from geological fractals of waterscape to the neural pathways of inner space.” [1]

Dan Sandin & collaborators, compilation featuring Spiral 1 (1975), Spiral 3, Spiral 5 PTL (1979), 12 min

A documentary covering the performances and technology used by Sandin and his collaborators in the 1970s. The compilation features:

5 minute Romp Through the IP, 1973 (Dan Sandin, Phil Morton)

Poop for the National Computer Conference, 1975 (Tom DeFanti, Phil Morton and Dan Sandin)

Spiral 1, 1975 (Rylin Harris, Dan Sandin and Tom DeFanti)

Spiral3 (Audio: Sticks Raboin, Bob Snyder; Video: Tom DeFanti, Phil Morton, Dan Sandin, Jane Veeder; Dance: Rylin Harris)

Spiral 5 PTL (Perhaps The Last), 1979 (Dan Sandin, Tom DeFanti and Mimi Shevitz)

Document of performance at Electronic Visualization Event 1 in Chicago, April 1975 (Raul Zaritsky and Jim Morrissette)

introduction: early personal image processors in the uS and japan

By Mia Parnall

Almost as soon as video emerged as a viable artistic medium in the late 1960s, there were attempts to doctor, manipulate, and synthesize it. In fact, at the first exhibit of video art at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1971, all the works shown had been 'processed' in some way. Initially available only in advanced systems such as television stations, video manipulation was difficult to access, yet through a DIY ethos surrounding technology, supported in the US by publications like Radical Software from 1970, and in Japan by collectives like Video Earth Tokyo, there was a drive to improve common access to and knowledge about the properties and possibilities of the medium. This text aims to offer a short introduction to two inventors of personal image-processing devices, Dan Sandin and Ko Nakajima.

In the late 1960s, then-physicist Dan Sandin's interest in image processing was beginning to emerge from his scientific background. First becoming interested in creating lightshows using chemical and optical techniques, he would soon begin teaching in the arts at the University of Illinois, before encountering video through the student protests of 1970. [2] These factors led to his development of and subsequent experimentation with one of the most successful early image-processing machines, the Sandin Image Processor (IP), in 1973.

The IP grew out of Sandin's search to develop a 'visual equivalent' to the 1964 Moog audio synthesizer which could modulate images (either recorded or computer-generated) instead of sounds - a goal which he began to pursue around 1968.[3] In theory, anyone could build their own Sandin Image Processor. Its real-time functionality enabled it to be used for performances, among them Sandin's artistic collaborations with Tom DeFanti, known as Electronic Visualization Events. These combined DeFanti's CG Graphics Symbiosis System (GraSS, famously used for a sequence in the first Star Wars film) with Sandin's analog processing device, resulting in works such as the Spiral series.

Forming the the EVL (Electronic Visualization Laboratory) at the University of Illinois, DeFanti and Sandin's aim was combining the complexity of language-based computer programming with the feedback-informed functionality of television. They were also committed to making their apparatus accessible, spawning a scene of artist-technicians in Chicago. Sandin, for example, encouraged others to build copies of the Image Processor, which was composed of modules that could be bought commercially. As part of his publication "Distribution Religion," he would freely publish instructions on how to construct and operate the IP, as well as record and distribute video tutorials.

Like Sandin, Ko Nakajima had already experimented with creating his own technology for projectors in his early animation works when he visited North America in 1967. He may have brushed paths with Sandin on this trip, as he spent time among the experimental artists and filmmakers of New York and attended Expo ‘67 in Montreal. The latter was an event of unprecedented futurism in technologies of moving-image display, including contributions by other early video artists such as Woody Vasulka, who was involved in the orchestration of the US Pavilion housed in Buckminster Fuller's dome, and countless multi-projection film screenings (a prototype of IMAX, entitled In The Labyrinth, formed one of the main events). It was also the event where Sony would exhibit its recently developed portable VTR, the Portapak, at the Japan Pavilion. On this trip Nakajima was exposed to international developments in screen media and the sheer potential for manipulating images through various technologies, as well as potentially experiments in real-time image-processing, leading him to seek out TV equipment in 1971 to do just this.

Up until the 1970s, advanced image-processing systems with intuitive manual controls were generally confined to television stations. For example, in 1969, Kohei Ando created his image-processing work Oh! My Mother through his employment at a broadcasting company. However, while the 1970 Paik-Abe Video Synthesizer is typically heralded as the first personal image-processing device, its inventors Nam June Paik and Shuya Abe were already working on it in 1964, and Eric Siegel and Stephen Beck were working on similar experiments in the US starting from 1968-9. In terms of artists working with computers (if not manual synthesisers), Stan Vanderbeek had already made 9 computer films by 1970, the Computer Techniques Group (CTG) were active in Japan, and graphic systems for synthesising both music and choreography through the computer were existent in the mid to late 1960s. [4] Already in 1967, computer engineer A. Michael Noll celebrated the computer as an artistic medium, and called for efforts toward developing "real time interaction" between computer and user. In his article “The digital computer as creative medium,” he expresses a wish to reduce the "rather long time delay between the running of the computer program and the production of the final graphical or acoustic output," thus "tightening the man-machine feedback loop... to generate either musical sounds or visual displays." [5] One way to do this was by applying real-time analog effects processing to CG images, as Sandin’s device would initially make possible.

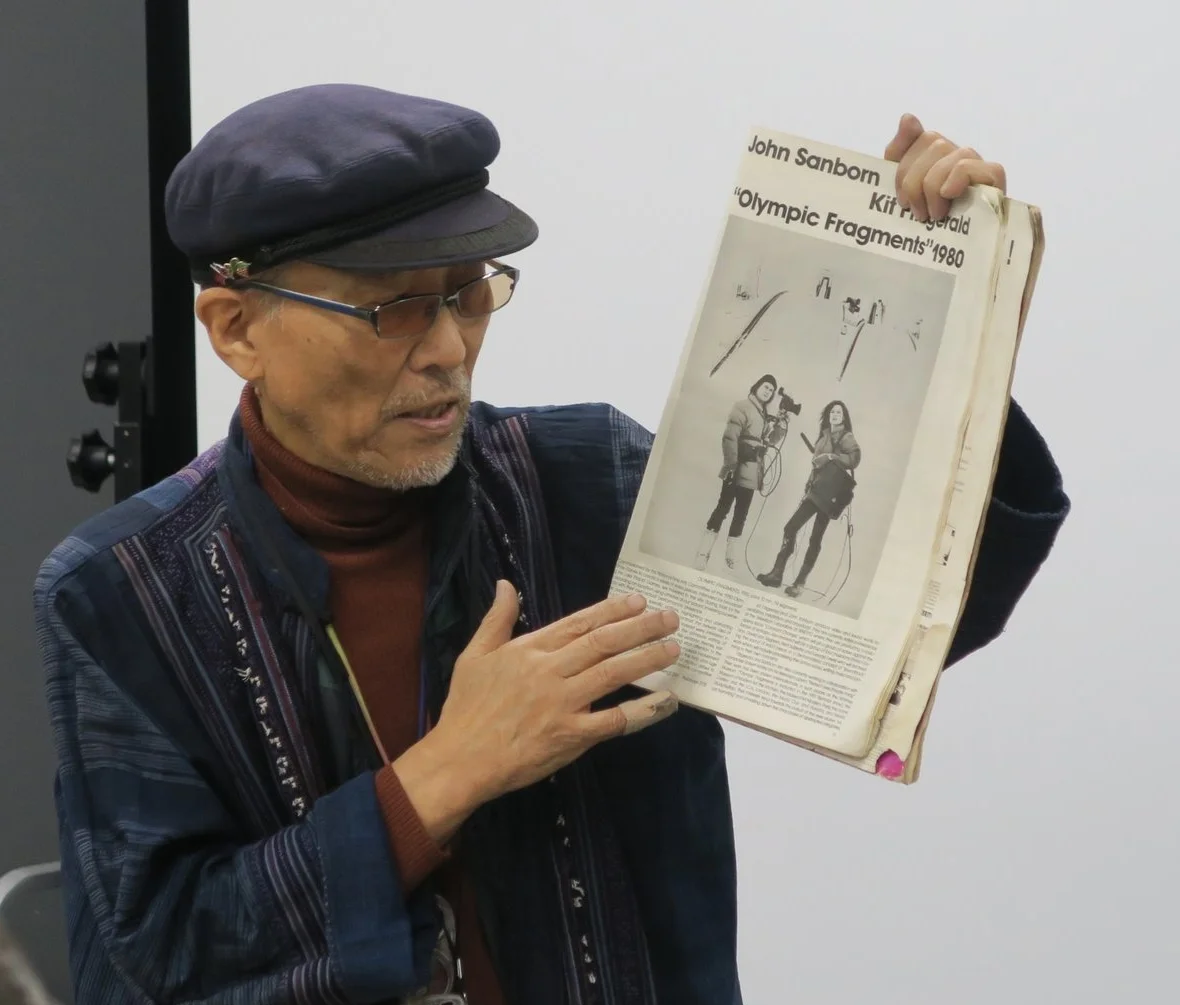

Then in the late 1970s and '80s, Nakajima teamed up with two Japanese electronics giants to create his own machines designed for personal use. These were the Animaker (1979), developed in collaboration with Sony, and the Aniputer (1982) developed with JVC. The Animaker, which automatically took frame-by-frame shots and performed effect processing, sold about 100 units, and its effects can be seen in works such as the Biological Cycle series. The Aniputer, by contrast, was a user-friendly computer graphics system - a personal portable computer integrated with a video camera which allowed any user to directly manipulate video and images on a screen, creating animations in real time. Controlled entirely by buttons and a joystick with no need for programming; whereas the Sandin Image Processor was large and customisable, Nakajima's devices were portable, commercial and ready-to-use. In the 1980s Nakajima would tour the US and Canada with his Aniputer, hosting workshops, demos and screenings.

As computer art widened in influence and Nakajima's inventions came to fruition, Sandin and Nakajima would come into closer contact through the international computer graphics conventions, SIGGRAPH, in which they both participated in the 1980s. Sandin was heavily involved with SIGGRAPH, not only displaying his works but presenting papers, hosting courses and participating in panels. Nakajima was also involved in SIGGRAPH from 1981 onwards, writing a series of articles about works and developments presented there for Japanese publication AVCC. Nakajima presented Mt. Fuji at SIGGRAPH in 1985 in San Francisco, where two installations by Sandin, Array of Julia Set Images and Hedgehog I, were also shown. That year, the 'ACM/SIGGRAPH Travelling Art Show' including Mt Fuji and a program of computer art from US and Canada, also came to Isetan in Shinjuku.

While very different in their user interfaces - one a customisable, build-your-own system and the other a consumer item - Sandin and Nakajima’s user-friendly image-processing inventions, and their investment in teaching others to use them, opened up the field of computer graphics and visual effects to a whole new bank of creators in the 1970s and 1980s. Both helped to free computer technology from its monopolisation by the state and corporations, and return the functionality and creativity of computers to everyday users. A joint statement released in the 1970s by Sandin and his collaborators read,

“The high priests of technology use unwieldy systems to perpetuate cybercrud–the art of using computers to put things over on people. This mentality can be countered by bringing to people systems that are easily learned and used–"habitable" systems.” [6]

Indeed, we can trace this attitude back to their earlier projects. Nakajima’s promotion of community-access television and Sandin’s involvement in activism in the late 1960s, both facilitated by the newfound availability of portable video equipment, could be said to prefigure the spirit of their later inventions. Both the Sandin Image Processor and the Aniputer embodied the idea of 'habitable systems,' and envisioned a world where computers were not just technologies of management and control, but of curiosity and creation.

[2] Furlong, Lucinda. "Tracking Video Art: "Image Processing" as a Genre.” Art Journal Vol.45 No.3 (Autumn 1985): 233-237, 237.

[3] Furlong, Lucinda. "Towards a history of image-processed video." AFTERIMAGE (Summer 1983): 35-38, 37.

[4] Noll, A. Michael. “The digital computer as creative medium.” IEEE Spectrum (October 1967): 89-95, 93.

[5] Noll, “The digital computer as creative medium,” 93.

[6] Furlong, "Tracking Video Art," 235.

Dan sandin

Daniel J. Sandin is an internationally recognized pioneer of electronic art and visualization. He is director emeritus of the Electronic Visualization Lab and a professor emeritus in the School of Art and Design at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He is continuing his professional activities with Tom DeFanti at Calit2, UCSD. As an artist, he has exhibited worldwide, and has received grants in support of his work from the Rockefeller Foundation, the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Science Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. His video animation Spiral PTL is in the inaugural collection of video art at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In 1969, Sandin developed a computer-controlled light and sound environment called Glow Flow at the Smithsonian Institution and was invited to join the art faculty at the University of Illinois the same year. By 1973, he had developed the Sandin Image Processor, a highly programmable analog computer for processing video images in real time. He then worked with DeFanti to combine the Image Processor with real-time computer graphics and performed visual concerts, the Electronic Visualization Events, with synthesized musical accompaniment. In 1991, Sandin and DeFanti conceived and developed, in collaboration with graduate students, the CAVE virtual reality (VR) theater.

In recent years, Sandin has been concentrating on the development of auto stereo VR displays (i.e., free viewing, no glasses), and on the creation of network-based tele-collaborative VR art works that involve video camera image materials, rich human interaction and mathematical systems.

Ko Nakajima

Ko Nakajima began his career in experimental animation with the creation of works such as Seizoki (1964). At his solo exhibition at the Sogetsu Art Center, a space for avant-garde art in 1960s Tokyo, he produced Seizoki by painting directly on the film between screenings. His perennial interest in integrating new technologies, exploring the potential of film, video, and eventually computer animation, joined his desire to explore human intersections with nature, as seen in his Biological Cycle series (1971-); he created the first work in the series, Biological Life (1971-), by copying manipulated film footage onto video, then further manipulating the work with a video synthesizer.

In 1971, Nakajima established Video Earth Tokyo, the pioneering video-art collective. Nakajima used one of the earliest available portable video recorders to document Video Earth Tokyo performance pieces and teach the new technology. Video Earth Tokyo members created works, broadcast works on cable television, and participated in international exhibitions and emergent CG (computer graphics) conferences. In 1982, Nakajima introduced his Aniputer. Aniputer technology allowed wide access to creation of video animation, as this personal portable computer integrated with a video camera, developed in collaboration with Japan Victor Company (JVC), allowed any user to directly manipulate video and images on a screen, creating animations in real time. Nakajima used his expertise manipulating film, photography, and video with computer technology to create what is perhaps his best known work, Mt. Fuji (1984), a ninety-minute rhythmic meditation on nature, spirituality, and perspective.

Nakajima has produced works in France, Canada, New Zealand, and Denmark. Representative works include Biological Cycle series (1971-), My Life series (1976-), Mt. Fuji (1984), and Dolmen (1987). His works are in permanent collections internationally, including in Centre Georges Pompidou (France), The Museum of Modern Art (U.S.), Long Beach Museum of Art Video Archive (U.S.), and the Getty Research Institute Special Collections (U.S.).

community of images: Japanese moving image artists in the uS, 1960s - 1970s

Community of Images: Japanese Moving Image Artists in the US, 1960s-1970s will be an exhibition of experimental moving images created by Japanese artists in the U.S. during the 1960s and 70s, an area that has fallen in the fissure between American and Japanese archival priorities. Following JASGP's Re:imagining Recovery Project and its mission to support and engage diverse audiences through Japanese arts and culture in collaboration with local organizations, this project aims to discover, preserve, and present film and video works and performance footage by Japanese filmmakers and artists to the wider public.

We have partnered with the University of the Arts, and will present this exhibition at the Philadelphia Arts Alliance in June - August 2024.

The project and its online programming is generously supported by the Pew Center for Arts and Heritage & the Andy Warhol Foundation.