Essay: TV as a Creative Medium (1969) by Shigeko Kubota

Shigeko Kubota's review of the TV as a Creative Medium exhibition at the Howard Wise Gallery, May 17 – June 14, 1969. Written for Japanese journal Bijutsu Techō in Japanese, translated into English in 2024 with permission of the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation.

Report from New York: TV as a Creative Medium (1969)

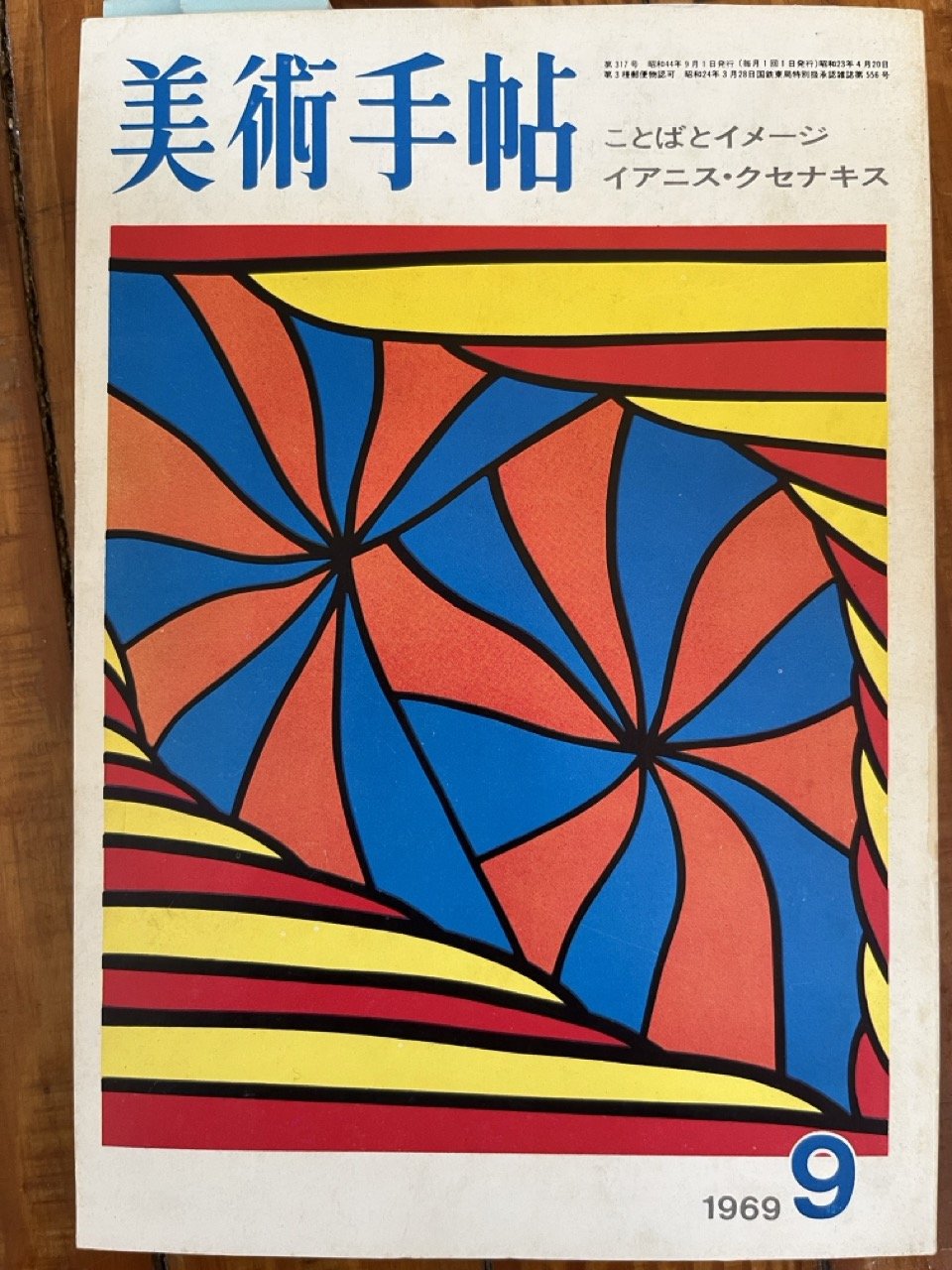

First published in:

Bijutsu Techō, September, 1969.

“The first generation of kids raised on TV are now young adults. As with any generation, some of them have become artists.

It’s only natural that young artists who grew up immersed in technology and molded by TV would use TV as a creative medium.”

Howard Wise Gallery champions kinetic art, which is often shunned by the gallery market due to its relative fragility. Now, the gallery has organized a group exhibition that showcases TV, the mass medium of the moment, as art.

The venue is dimly lit and has a somewhat confined feel, consisting of two rooms connected in a question-mark formation. Twenty-five TV sets, representing the work of ten TV artists, are spatially arranged in a manner recalling storefronts of TV shops in Akihabara, Tokyo.

On stepping from the elevator directly into the venue, you encounter Wipe Cycle, an electronic mural consisting of nine TV sets. This collaborative work by Frank Gillette (b. 1941 in New Jersey) and Ira Schneider (b. 1939 in New York) employs a delay line, an approach that has been popular of late, and presents a TV collage that mixes real-time and delayed on-site camera footage with other “information” (images from commercial television).

First, real-time footage of viewers themselves appears on one of the screens; then, after an eight-second time lag, it flashes onto the screen to the right, and then repeats again after sixteen seconds.

This description doesn’t really convey the work’s impact, but when we see our own unconscious actions from a few seconds before (gestures of which we are unaware, such as opening a handbag or grabbing a friend’s arm) repeated like an echo on the TV screen, we can be immobilized by embarrassment. The experience speaks to what Time magazine has described as “confusion of our conception of space-time unique to the electronic age .”

[Image captions]

Above / below: Thomas Tadlock, The Archetron

Charlotte Moorman

TV Bra for Living Sculpture

Frank Gillette and Ira Schneider, Wipe Cycle

Paul Ryan, Everyman’s Moebius Strip

Nam June Paik, Participation TV I

Eric Siegel, Psychedelevision in Color

The next thing one notices is sure to be Charlotte Moorman, who has been an increasingly glamorous presence lately, bare except for a brassiere consisting of two transistor TVs. She greets people with a volley of enthusiastic “Hi,” “Hi,” in her charming Texas drawl, and blows kisses. Without her cello, she hardly seems to be there, but upon sitting in a chair, she is transformed into a “living sculpture.” She plays the cello, and the picture on the TV bra is altered and modulated by the degree of energy with which she bows it. A baseball player displayed on the screen pitches wildly and violates the rules of the game. This passionately Dadaistic work, TV Bra for Living Sculpture, is the brainchild of Nam June Paik.

Thomas Tadlock (b. 1941 in Washington, D.C.), a light sculptor who until five years ago also studied design, presents The Archetron, a psychedelic, kaleidoscopic, automatically shape- and color-changing TV piece. It resembles the flowing stained glass of a Catholic cathedral, and immerses us in a phantasmagoric synthesis of electronics and psychoactive drugs.

“Previously, I used light bulbs to produce light machines and light sculptures, but conventional kinetic light machines could not produce the complex images I wanted, so I inevitably got involved with TV,” he explains.

The kaleidoscopic The Archetron took two years to complete, was funded by $10,000 from patrons, and is currently priced at $25,000.

Tadlock’s kaleidoscope is a piece of mood-making TV art that would be an ideal fit for Nam June Paik’s proposed TV program The Silent TV Station, as would Eric Siegel’s (b. 1944 in New York) Psychedelevision in Color. The latter, also a mood-setting TV piece, comprises twenty-one minutes of footage on videotape, shown on a color TV and set to records by Tchaikovsky and the Beatles. Siegel’s work demonstrates how sound can transform visuals with spectacular impact, as in the Hollywood film 2001: A Space Odyssey. It contains a scene where Albert Einstein’s face burns and melts, and the vivid colors convey the ecstasy of a psychedelic drug experience.

Siegel was a brilliant young engineer, and at the age of fifteen he won Second Prize at the 1960 N.Y.C. Science Fair for his home-made closed-circuit TV built from second-hand tubes, microscope lenses, and other scrounged parts. He graduated from a technical high school, and has become an artist of the new TV generation, thoroughly focused on technology and unaware even of such seminal avant-garde art figures as Allan Kaprow.

Earl Reiback (b. 1936 in New York) takes an entirely different approach. A nuclear physicist and graduate of MIT, he received support from RCA for a project in which he removed the color phosphor from TVs and reapplied phosphor directly inside the cathode-ray tubes. His TV sets display images in pale blue and pink, resembling layers of thin ice overlapping.

Aldo Tambellini (b. 1930 in New York), who has showcased Japanese avant-garde artists at the Gate Theater, participated alongside Tadlock, Otto Piene, Kaprow, Paik, and George Stadnik in the program The Medium is the Medium at the Boston public television station WGBH in February 1969. Tambellini’s work in this show, Black Spiral, is understated and tends to get overshadowed here, yet it exerts a quiet, almost nonexistent presence.

[Image caption]

Aldo Tambellini, Black Spiral

In one corner of the venue, separated by white curtains and reminiscent of a psychiatric hospital’s consultation room, is Everyman’s Moebius Strip, an

interactive artwork employing VTR by Paul Ryan (b. 1943 in New York). Ryan, who formerly served as Marshall McLuhan’s research assistant, briefly instructs the viewer on how to operate the VTR, then steps outside the curtain. The viewer is left alone with the video deck in this sealed-off space.

Suddenly becoming drowsy, I lean back in my chair and close my eyes for two or three seconds. Then I slowly open my eyes, look at the ceiling and walls around me, and widen my eyes for four or five seconds before switching off the VTR to stop recording. Next, I watch what I have just done on the screen, with the footage appearing after a time lag of a few minutes. I’m no narcissist, but watching the video of me alone inside the white curtains, I’m crestfallen at how my face looks on the TV screen. I can’t believe it’s really me, and flick the switch off midway through.

When I step outside the white curtains, Ryan asks me how it was, in a tone like a psychologist treating a neurotic patient. This approach, using VTR to reverse the external and the internal, and vice versa, is actually used in psychoanalysis.

Ryan explains, “The ‘you’ that appears on the VTR is the intended image that you present to the outside world. But when you see the image of yourself watching yourself on tape, you are actually seeing your true, inner self.”

What we see in the TV as a Creative Medium exhibition is a move toward direct public participation, reclaiming televised culture from the establishment and reshaping it into a two-way, multifaceted mode of communication that truly suits its electronic nature.

Gillette and Schneider’s delay line piece Wipe Cycle and Ryan’s Everyman’s Moebius Strip involve direct audience participation in creating TV works, and Paik’s pair of works Participation TV I and II are similar experiments.

Participation TV I features a color TV, on which the viewer’s shadow appears in three primary hues, with varying degrees of light and darkness, on the screen when they stand in front of the TV. When the viewer interacts with various objects, the interactions are fed back as electronic abstractions. When a flashlight is shone on an object’s surface, the actual details of the lit area are revealed.

Participation TV II features audio interaction. Specifically, the viewer’s utterances, whistles, coughs and so forth are converted into sound waves that generate interference patterns on a color TV screen. Meanwhile, Joe Weintraub’s AC/TV (Audio-Controlled Television) undertakes a similar experiment using radio sound waves.

Electronic music composers who feel a certain dissatisfaction with tape music have already begun using live electronics in performances and improvisations, in a manner quite similar to theatrical pieces. At the TV as a Creative Medium venue, we see the concept of live electronics expanded to video, creating an experiential environment for audience participation in TV.

The industry, for its part, is preparing to assimilate these advances on the part of artists. Paul Ryan commandeered, from a stock-brokerage source, a forecast prepared by the renowned industry consultancy Arthur D. Little. According to this document, by 1973, color TV cameras and color VTRs will drop to one-tenth of their current price, generating a $250 million business, and soon people will be creating their own color TV programs as easily as taking photos. What’s more, cable TV capable of transmitting up to fifty channels is expected to generate about $500 million in annual revenue. Meanwhile, CBS is planning to launch an EVR (Electronic Video Recording) disk that can be produced as easily and cheaply as an LP record, sparking a transition from conventional one-way TV culture to a multifaceted video lifestyle.

This has led public TV stations to support and foster experimentation by artists. In San Francisco, KQED invited avant-garde creators such as Yvonne Rainer to conduct experiments, drawing on a $100,000 public-sector budget. In Boston, WGBH’s Fred Barzyk is planning a major Participation TV Festival for next year, featuring such prominent figures as Allan Kaprow, Stan VanDerBeek, and Nam June Paik.

Finally, to summarize the outlook for the future, based on what I heard from a variety of related persons:

Two defining characteristics of the 1960s were the drug culture, which involves voyages into the inner space of human consciousness, and electronic culture, which involves expansion outward. Among the younger generation, there is a natural tendency to integrate the two. Currently, two books on the contemporary avant-garde are scheduled for publication—one by Gene Youngblood on the West Coast, another by Frank Gillette and Paul Ryan in the East – both of which will explore the psychedelic metaphysics of electronics.

As many have observed, in the society of today and tomorrow, transportation and transmission are more important than production. In this context, can the conventional arts endure, when originals are seldom seen and we must be satisfied with color reproductions? Artworks that can be easily mailed or transmitted in their original form via VTR and communication satellites are surely poised to grow in importance.

With movements such as Fluxus, we have seen the proliferation of multiples. Might the logical conclusion of this approach ultimately be TV-based works?

In the end, might the history of art mirror that of cinema, with mass-produced films eclipsing theater, and music, with record sales surpassing live concerts and giving rise to a huge industry? Even photography, which has relatively low visual impact and versatility compared to other media, has already evolved into a legitimate art form. If TV art – which can be reproduced as easily as a photograph, while offering far wider scope for visual experimentation than oil painting – becomes a fully mature art form, it will surely spark a revolution in the arts of the future.

Shigeko Kubota lives and works in New York City.

*TV as a Creative Medium, Howard Wise Gallery, May 17 – June 14, 1969

Shigeko Kubota's review of the TV as a Creative Medium exhibition at the Howard Wise Gallery, May 17 – June 14, 1969. Written for Japanese journal Bijutsu Techō in Japanese, translated into English in 2024 with permission of the Shigeko Kubota Video Art Foundation. Translated by Colin Smith.