Essay: Video as Biological Cycle: Ko Nakajima's Ecological Vision

Scholar Nina Horisaki-Christens writes about Ko Nakajima’s ecological visions.

essay: NINA HORISAKI-CHRISTENS

Video as Biological Cycle: Ko Nakajima’s Ecological Vision

Ko Nakajima’s first film, Anapoko (1963), seems to bring matter to life. In the opening frames, a flash of glowing pink, red, and yellow gradients are overlaid with a light-colored oval-shaped dancing splotch that inverts into a dark, textured, egg-shaped crust made of some sort of opaque material that sits on the surface of the translucent film substrate. Much like Stan Brakhage’s Mothlight (1963), the irregularities inherent to placing material on film by hand lead to an instability in the image, causing it to jump around from frame to frame. But unlike Brakhage, Nakajima exerts control over this process so that the splotch retains a semblance of consistency from across frames. Flickering between material and image, the film produces a sense of real space and time that defies the illusionistic conventions of traditional animation, while still gesturing toward the ability of a succession of frames to set image in motion. Yet here successive frames do not consist of the standard photographic reproduction of hand-inked layers of cels; rather, they consist of handmade drawings written directly on the 8mm film strip itself—a technique Nakajima refers to as “kaki-mation,” from the Japanese word kaku or kakimasu (to draw). Skipping the processes of reproductive media, the film sets the matter, in the form of permanent marker ink and scratched emulsion on the acetate film base, into motion. This may seem a minor technical matter; Nakajima himself often frames this choice as a practical issue of the cost savings achieved by drawing directly on leftover film procured from friends in the industry, thereby avoiding developing and processing fees. But Nakajima is also an artist attuned to the nuances of technical processes and media histories. Given that he produced this work at a moment in which ecological understandings of the world were gaining traction, and keeping in mind the biological imagery that develops over the course of the film itself, it is hard to imagine that there is not a critique of the human-centered worldview that lies behind his animation of matter. In fact, the ecological critique of human-centric worldviews is a recurring concern of Nakajima’s across his practice, which helps explain the privileged role of video within his artistic production.

Ko Nakajima, Anapoko, 1963, 16mm transferred to video, 7:00 min, color, sound. (excerpt)

Ko Nakajima, Seizoki, 1964, 4 min, 16mm film transferred to video, color, sound. (excerpt)

Anapoko develops from this initial, egg-like passage into a set of rough, bulging eyes, just as a rounded body starts to take shape within the shifting outline of an elliptical form. Gradually, a tail and set of fins grow as the body narrows, metamorphosing into a wagging, segmented body and flapping wings reminiscent of a primordial dragonfly, except that the eyes now protrude from stalks. The body curls around from left to right, shifting directions to head off-screen as a fish-like mouth appears on the left, growing larger as it chomps its way across the screen, eventually enveloping the primordial insect. The insect decomposes into a squiggle as the fish-body moves across the screen until, finally, the squiggle emerges from the tail end of the fish form as an ovoid that begins a new metamorphic process. Anapoko was produced in 1963, one year after the publication in English of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (though still a year before its translation into Japanese), several years after the discovery of Minamata disease—mercury poisoning from industrial run-off—and the same year it was confirmed by scientists to have been caused by Chisso Corporation. A renewed consciousness of the connectedness of natural environments that would continue to build into the early 1970s had already started to form. This was also well into the economic miracles of Japan’s 1960s high growth period, spurred by industrialization and major urban redevelopment projects like those that preceded the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Connections to this context are not explicitly depicted in this film, but his next film, Seizoki (1964) can be read as linking this biological preoccupation to technology, industrial society, and urban environments. The film depicts the movement and development of fluid-like material through what appear to be mass manufactured tubes and scientific glassware, into and out of picture frames, and over urban traffic including cars and crowds of pedestrians. That the film’s title refers to the reproductive organs of primitive plant life, from algae to ferns, sets up a parallel between the reproductive processes of moving image animation and biological reproduction. Indeed, animation functions analogously through the repetition of a sequence of extremely similar images. But produced again through Nakajima’s kaki-mation method of hand drawing, the repetition here is not only imprecise, it is itself altered through the scratches and damage that accumulate when the drawings on the surface of the film are scraped though the projector mechanisms. No two screenings of the physical film will be entirely the same, pushing against the mechanical precision of industrial products and newly improved urban infrastructures.

This interplay between the precision of industrial production and the messiness of organic reproduction is critical within the 1960s context. The rapid processes of urbanization and proliferation of mass media that accompanied the economic high growth period in Japan led to a conflation of glossy, mechanically reproduced commercial images with urban streets and cityscapes. Writing for the journal Kikan Firumu (Film quarterly) in 1972, designer Kiyoshi Awazu describes contemporary life as defined by conditions of technological reproduction, intimately tied with the production of images:

We use reproductions, we receive reproduced messages, we wear reproduced goods, we live inside reproduced goods, and we walk through such streets. Graphism is the mode of today. Everything that is there is processed nature, processed landscape…the people of today are already performing the inverted play that is the state of being possessed by images.[i]

As art historian Michio Hayashi has argued, the terms graphism and graphication gained currency across a variety of artistic fields in 1960s Tokyo, referring both to linear drawing and “the technology of reproduction, as in words such as photography and lithography.”[ii] Hayashi argues that these two meanings of the graphic intersect in the act of tracing as it “simultaneously opens up the possibility of repetitive tracing and its technological mediation,” linking the mechanical to the manual.[iii] If, for Awazu, the answer to the overbearing power of graphism is a primitive trace that defies immediate signification in order to resist the regulating impulse of urban space, for Nakajima it appears to be the most basic events—life and death—within biological cycles that retain some potential for resistance.

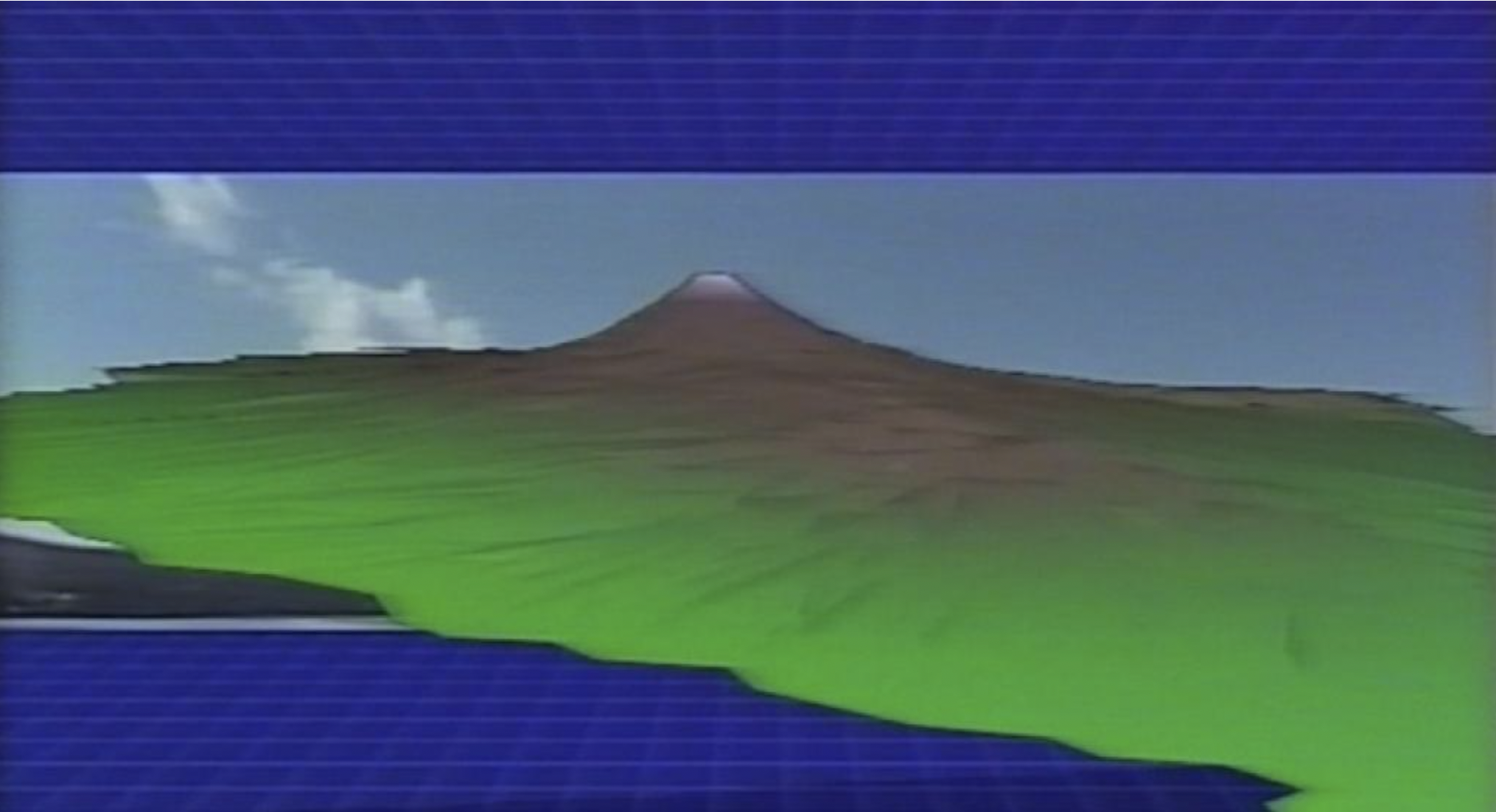

However, as Nakajima begins to pick up video in the early 1970s, we can start to sense within this medium an added layer of meaning in regard to these biological cycles. Analog video in the early 1970s is generally described as the antithesis of television: a process-based medium that has the potential to be rewritten each time it is replayed due to the instability of the magnetic tape on which it is recorded, a quality that likens it to performance. But these chance alterations in playback are also understood as one form of feedback, further modifiable by intentional feedback via cameras and video synthesizers, that evokes a generative potential for the video medium. In the wake of systems thinking in cybernetics, these feedback processes are understood as models of emergent natural phenomena. Thus when Nakajima describes his practice since the 1970s as a search for the algorithms of nature in order to better understand the mechanisms of Earth’s environment, it is clear he views such systems thinking as a means of accessing unprocessed reality.[iv] Video, as a medium associated with process rather than product, and with multidirectional networked systems rather than a unidirectional wheel-and-spoke model, lends itself to Nakajima’s pursuit of non-destructive technology in which he can “use the computer to go back to nature.”[v] And, in fact, within early video discourse, this link to nature is not a stretch. As Ina Blom recounts in her analysis of the theoretical implications of early video practices, the televisual scanning process was recognized to have a biological equivalent in the form of copilia quadrata, a translucent three-millimeter-long copepod with an eye structure in which an anterior lens feeds light to a continuously independently moving posterior lens that then sends signals down a single neural channel, converting spatial information into linear, time-based transmissions. The contemporary rediscovery of copilia occured in the summer of 1963, so its appearance here must be a fluke, but its form bears a passing resemblance to the insect-like life form in Anapoko before it sprouts fins or wings. More to the point, however, copilia’s scanning eye, found only in the females, was discovered in 1972 to be the basis of the species’ reproductive system as it is this unique visual organ that allows it to find a flashing green light emitted by the male and to biologically reproduce.[vi] The televisual scanning process of analog video is thus found to be a literal means of biological reproduction in nature, reinforcing the generative potential of the video medium.

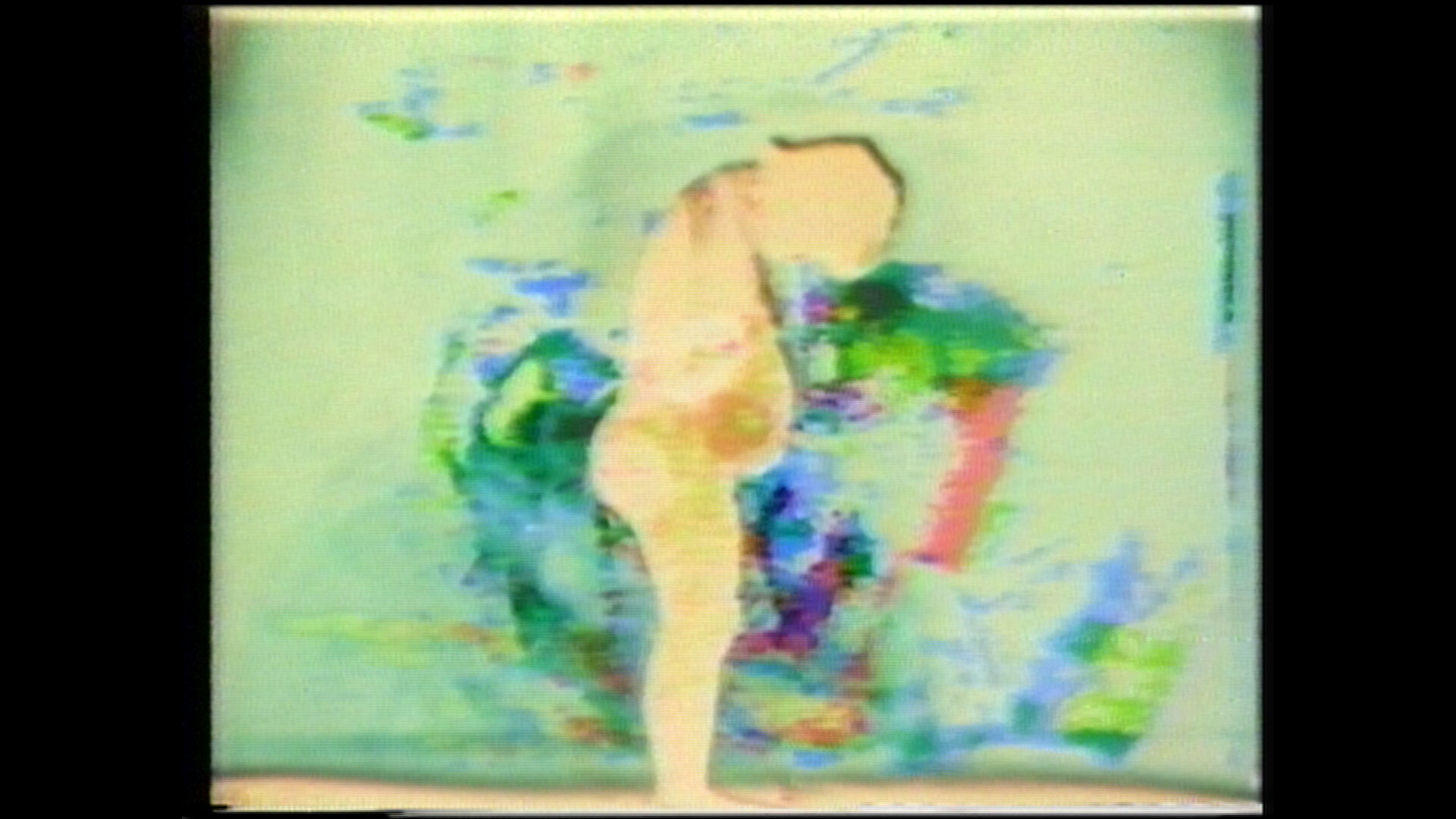

Ko Nakajima, Biological Cycle No. 2, 1971-1982, 1-inch transferred to digital file, 8:18 min.

In his most extensive video series, Biological Cycle (Ikimonogaku-teki saikuru, 1971-1985) and My Life (1971-), Nakajima pushes this reproductive connection through characteristic attributes of the video medium. Biological Cycle is a non-narrative work featuring a robot and a crane walking around, a man crawling and pedaling a stationary cycle, and a pregnant woman standing and holding an umbrella or stroking her bulging belly. The images—originally shot on high contrast black and white film then altered by kaki-mation, superimposition of positive and negative, and eventually video processing—shift between purples, teals, and magentas, vibrating from the irregularities of the kaki-mation technique and the offset doubling of movements from superimposition. The video techniques further disrupt and recompose the images, interjecting noise and performing feedback cycles on the intermingling images of human (man and woman) and machine (robot and stationary cycle). This generative potential of man and machine found in video intersects with the organic, reproductive potential—imperfect and mixed with noise to create non-identical offspring—gestured to by the inclusion of the pregnant woman and ostrich. A continuum is formed that positions man, nature, and machine as part of an inextricable system: an ecological continuum.

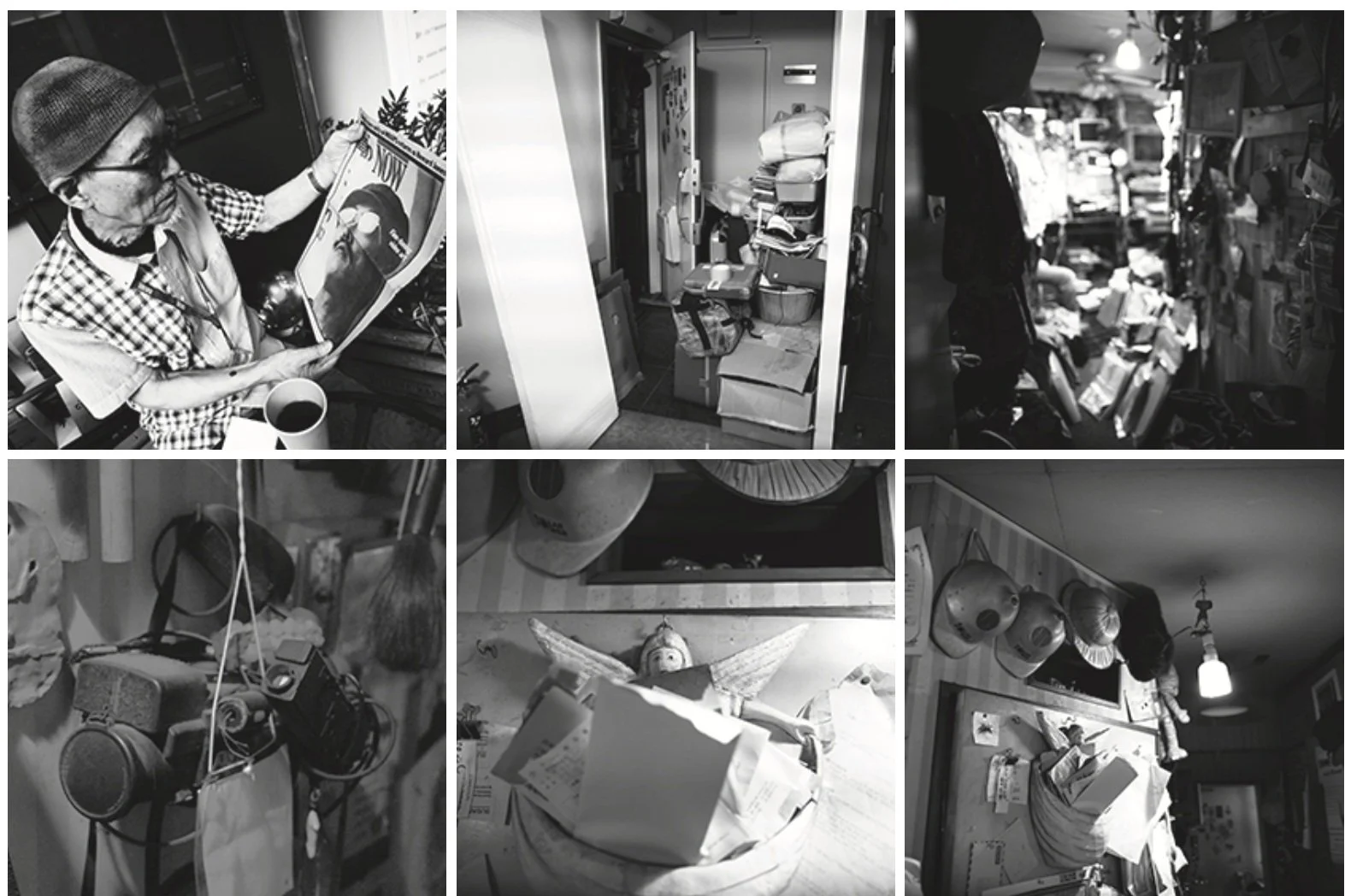

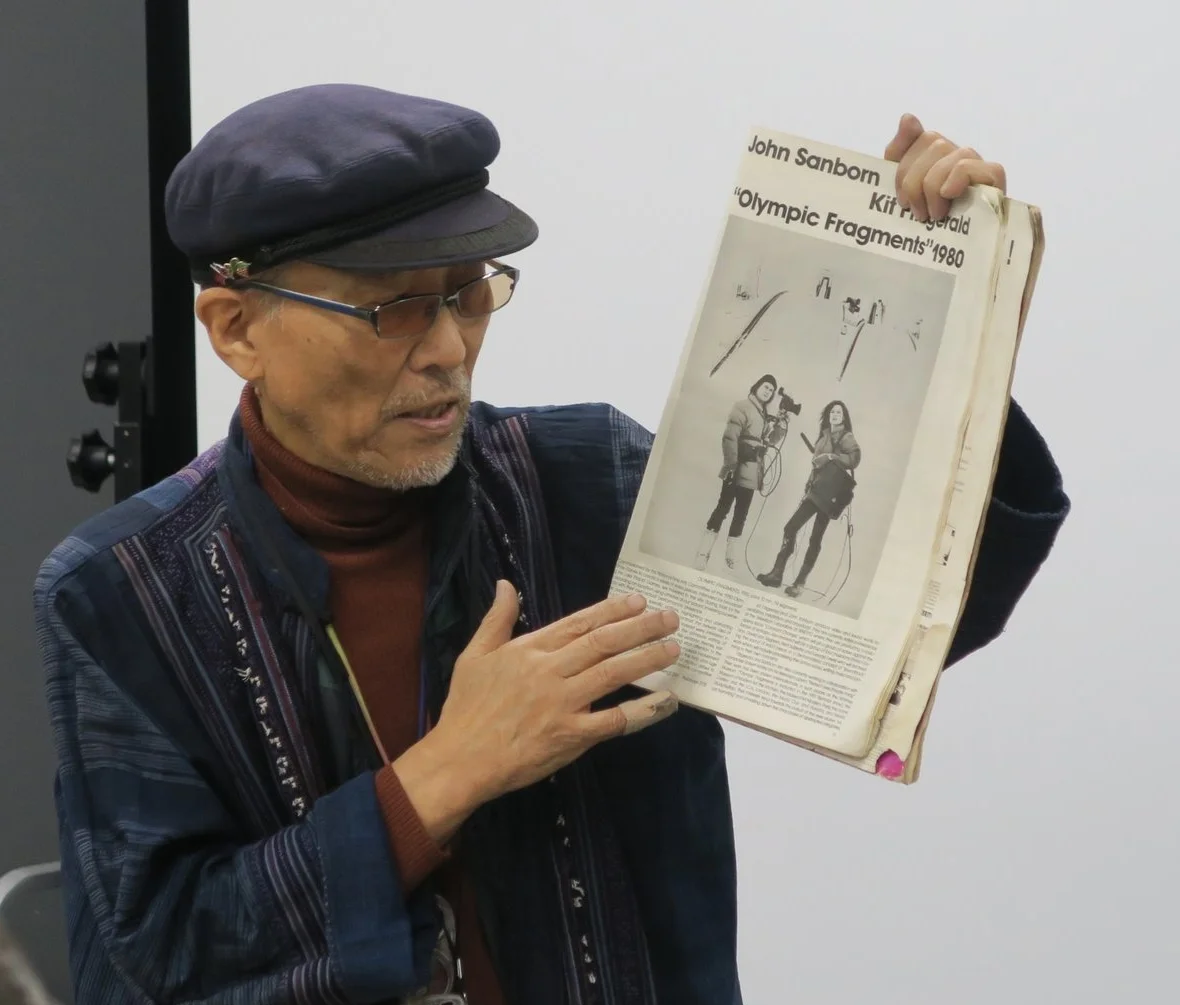

The ecological continuum precludes an exterior view as it incorporates all actors within the network, including the video camera itself. Artist Paul Ryan, who also sought the ecological potential of the video medium, considered his 1971 twelve-hour marathon work Video Wake for My Father—produced after his father’s death by recording his reactions to footage of his father when he was alive—as a failure because its combination of familial and technological analysis was “too rooted in the idea of criticism and examination,” thus relying on a third-person view.[vii] The ecological view lives more in the flat, unedited presentation of relationships and lived time and space, a project Nakajima has been pursing in My Life since 1974. Nakajima, too, was inspired by the death of a parent—in this case his mother—but also by the birth of a daughter. Starting with these two events, he documents the mundane experiences of emotional moments from his life in which the precariousness of life comes into focus—death, birth, illness. Rather than cutting them together in montage, they are placed side by side, allowing for some sense of comparison but precluding total immersion in either. This split attention and the prosaic details captured by the narrow frame and hand-held documentary approach of Nakajima’s video camera lend a first-person feel to the work that refuses exteriority and pure objectivity. As his life continues, Nakajima continues to add new scenes to the work, but he imagines this piece as extending beyond his lifetime, incorporating his own death and the lives of his offspring through the contributions of his descendants; the precision of cutting-edge, high-definition imaging media; and the decision-making potential of an AI editor. For Nakajima, such an ambition can be achieved specifically because of the generative potential he sees in the technological advances of digital video and artificial intelligence.

I would posit this as the core of Nakajima’s ecological vision: an unending process that reveals networks of relations while deemphasizing authorship, human-centered approaches, and physical production. The entirety of his artistic production is conceptualized as a connected cycle looping back on itself without resolution. The filmstrips from his 1960s productions are incorporated back into new collaborations with fashion designers; his video works take multiple forms and continue to be reworked—color contrasts are heightened, interludes inserted, etc.—as they get transferred to more contemporary media. If Matsuzawa Yutaka, whose Psi Room Nakajima photographed passionately in 1969, renounced the production of objects, Nakajima takes a video-inspired approach, constantly reusing, reediting, and reperforming his works in relation to contemporary technology and society. Matter is not so much produced as reused, modeled after the feedback systems that tie video processes to biological cycles. Although always concerned with the relation between humans, nature, and technology, this refusal of completion serves to decenter human control and human production so as to point an ecological path forward in which technology allows us to develop a healthier relationship with our surroundings.

[i] Kiyoshi Awazu, “Graphism,” in “Gendai eiga jyōkyō jiten,” ed. Akasegawa Genpei et. al., Kikan firumu 13 (December 1972): 117.

[ii] Michio Hayashi, “Tracing the Graphic in Postwar Japanese Art,” in Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde, ed. Doryun Chong (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 95.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ko Nakajima, “Bideo sakuhin to insutarēshon sakuhin no kaisetu” (unpublished typewritten statement, undated), PDF file, message to author, January 30, 2019.

[v] Belinda Meares, “VIDEO: Nature friendly video artist,” OnFilm 5, No. 6 (October-November 1988): 35.

[vi] Ina Blom, The Autobiography of Video: The Life and Times of a Memory Technology (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016), 92-93.

[vii] Blom, 87.

Nina Horisaki-Christens

Nina Horisaki-Christens is an art historian, curator, translator, and PhD Candidate in the Department of Art History and Archaeology and the Institute for Comparative Literature and Society at Columbia University (NY). She was a 2017-18 Fulbright Graduate Research Fellow and a visiting researcher at the Institute of Comparative Culture at Sophia University from 2017-2019, where she investigated the development of video practices by Tokyo-based artists in the 1970s. She assisted with the Japan Society's 2019 exhibition "Made in Tokyo: Architecture & Living, 1964/2020," served as Research Assistant for "Gutai: Splendid Playground" at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (2013), was a 2012-13 Helena Rubinstein Curatorial Fellow in the Whitney Museum's Independent Study Program, and previously worked as Assistant Curator and Interim Programs Manager at Art in General. She has also contributed to publications produced by ArtAsiaPacific, Art Tower Mito, the Mori Art Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, ArtPhil, Takuro Someya Gallery, Art in General, and Hyperallergic, and produced translations for Josai University's Review of Japanese Culture and Society, Bunka-cho Art Platform Japan (forthcoming), and Tokyo Opera City, among others.

This essay was originally published in:

Pleating Machine 3: Introduction to Archives XIX Ko Nakajima–MY LIFE catalogue (KUAC-C 41)

Edited by Hitoshi Kubo (Keio University Art Center). Editing Support by Ryosuke Yamakoshi, Shinpei Tsunefuka, Kahlua Tsunoda, Shiho Hasegawa. Designed by Hitoshi Kubo. Printed by Digital Graphic Co.,Ltd.. Paper is Kozupika by Yoshimori Co.,Ltd.. Published by Keio University Art Center. 108-8345 2-15-45 Mita Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan. Tel.03-5427-1621 © 9th Sep. 2019 | Keio University Art Center