More Than Cinema: Jonouchi Motoharu and Keiichi Tanaami

During the COVID-19 closure, the following is a digital viewing of the exhibition, More Than Cinema: Motoharu Jonouchi and Keiichi Tanaami co-presented by CCJ and Pioneer Works, co-curated by Go Hirasawa, Julian Ross, and Ann Adachi-Tasch.

more than cinema: Motoharu Jonouchi and Keiichi Tanaami

(March 6 — November 22, 2020 at Pioneer Works)

The following is a digital walkthrough of this exhibition co-presented by CCJ and Pioneer Works, co-curated by Go Hirasawa, Julian Ross, and Ann Adachi-Tasch.

More Than Cinema presents four film works by Motoharu Jonouchi (b. 1935 in Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan) and Keiichi Tanaami (b. 1936 in Tokyo, Japan) that illustrate the emergence and dynamism of the Expanded Cinema movement in Japan, which brought on similar experiments to that of the US and Europe that asked viewers to reconsider traditional frameworks of film viewing, such as narrative arcs, the suspension of disbelief, and the theater space. Instead, Expanded Cinema proponents adopted multiple projections, looping techniques, live performance, and other hybrid forms to focus attention on the human body and space itself. The exhibition follows research and preservation efforts by the non-profit organization Collaborative Cataloging Japan (CCJ).

Presented by Pioneer Works, More Than Cinema is organized by Collaborative Cataloging Japan, and curated by Go Hirasawa, Julian Ross, and Ann Adachi-Tasch. It was made possible with generous support from the National Endowment of the Arts, the Japan Foundation, New York, and W.L.S. Spencer Foundation.

Installation photographs courtesy of Collaborative Cataloging Japan and Pioneer Works.

Motoharu Jonouchi

Document 6.15, 1961-62

The discussions around the terms of Expanded Cinema and Intermedia as loanwords, entered into discourse in Japan in the mid-1960s, first appearing in journals by artists who had traveled to the US. Even prior to 1966 and 1967, when the term Expanded Cinema gained currency in Japan, Motoharu Jonouchi was carrying out similar experiments as leader of the VAN Film Science Research Center (VAN Eiga Kagaku Kenkyujo)—a place where filmmakers could assemble alongside people working in various media. Out of this interaction emerged Document 6.15 (1961-62), commissioned by the All-Japan Federation of Students’ Self-Governing Associations (Zengakuren) for a memorial service in 1961, marking one year since the start of anti-Anpo US-Japan Security Treaty demonstrations.

Motoharu Jonouchi, Document 6.15, 1961-62, 16mm transferred to video, silent, B&W, 13 minutes

Motoharu Jonouchi, Unedited footage for Document 6.15, 1960, 16mm transferred to video, silent, B&W, Three monitors, 26 minutes of footage total

A documentation of the struggle against the Japan-US Security Treaty of 1960, Document 6.15 was screened at the memorial assembly for Michiko Kanba, a student who was killed at the demonstration in front of the Diet Building. Considered the first expanded cinema experiment in Japan, the event included symbolic close-up images of Kanba along with the scenes of police brutality, with two different soundtracks, slide projections of paintings, and a live performance. Because it was a screening within a happening-like event without much documentation, a reconstruction of the original is impossible. Researcher and co-curator Go Hirasawa has found negatives that may have been part of the original screening. By digitizing this footage that’s not included in the final work, the curators aimed to reimagine the original context in which the work was presented, in consultation with people who were present.

One anonymous member of VAN noted, “We thought this ‘work’ would probably be a one-time-only event. We had never wanted to make a complete, perfect work to begin with, and for me at least, it is inappropriate even to call it a ‘work.’ Light was shed on an invisible state of affairs, which encompassed Zengakuren as well. I believe that creating a certain ‘situation’ was an essential part of the production.” Casting doubt on the standard model of a film screening, where a film is projected on a screen and the audience is expected to passively watch it, the work raised formal and theoretical questions around the medium. The political crux of Intermedia, as coined by Dick Higgins to instigate a critical spectatorship and stimulate audiences into participation was achieved many years prior to the arrival and subsequent discussion of the term.

Nichidai Eiken and VAN Film Science Research Center

Nihon University Film Study Club, a.k.a. Nichidai Eiken (Nihon Daigaku Eiga Kenkyukai) was founded in 1957 by Hirano Katsumi, Kanbara Hiroshi, Taniyama (Koh) Hiroh, Motoharu Jonouchi and others. During the campaign against the 1960 US-Japan Security Treaty, Jonouchi and associates fully participated in the protest movement while continuously documenting it from the inside, rather than from an objective outsider’s perspective. Nichidai Eiken was reorganized into the New Film Study Club, and key members, including Motoharu Jonouchi, Hiroshi Kanbara, and Masao Adachi, established the VAN Film Science Research Center as a space to both live in and produce films together. Out of their interaction grew a large number of interdisciplinary projects. Among the best-known works or events are Document 6.15 (1961) and Closed Vagina (Sain, 1963). With Adachi and Jonouchi remaining active artists and critical voices in the Japanese art community of the late 1960s, the political potential they saw in the fusion between different media informed the ways in which Intermedia was discussed later in the decade.

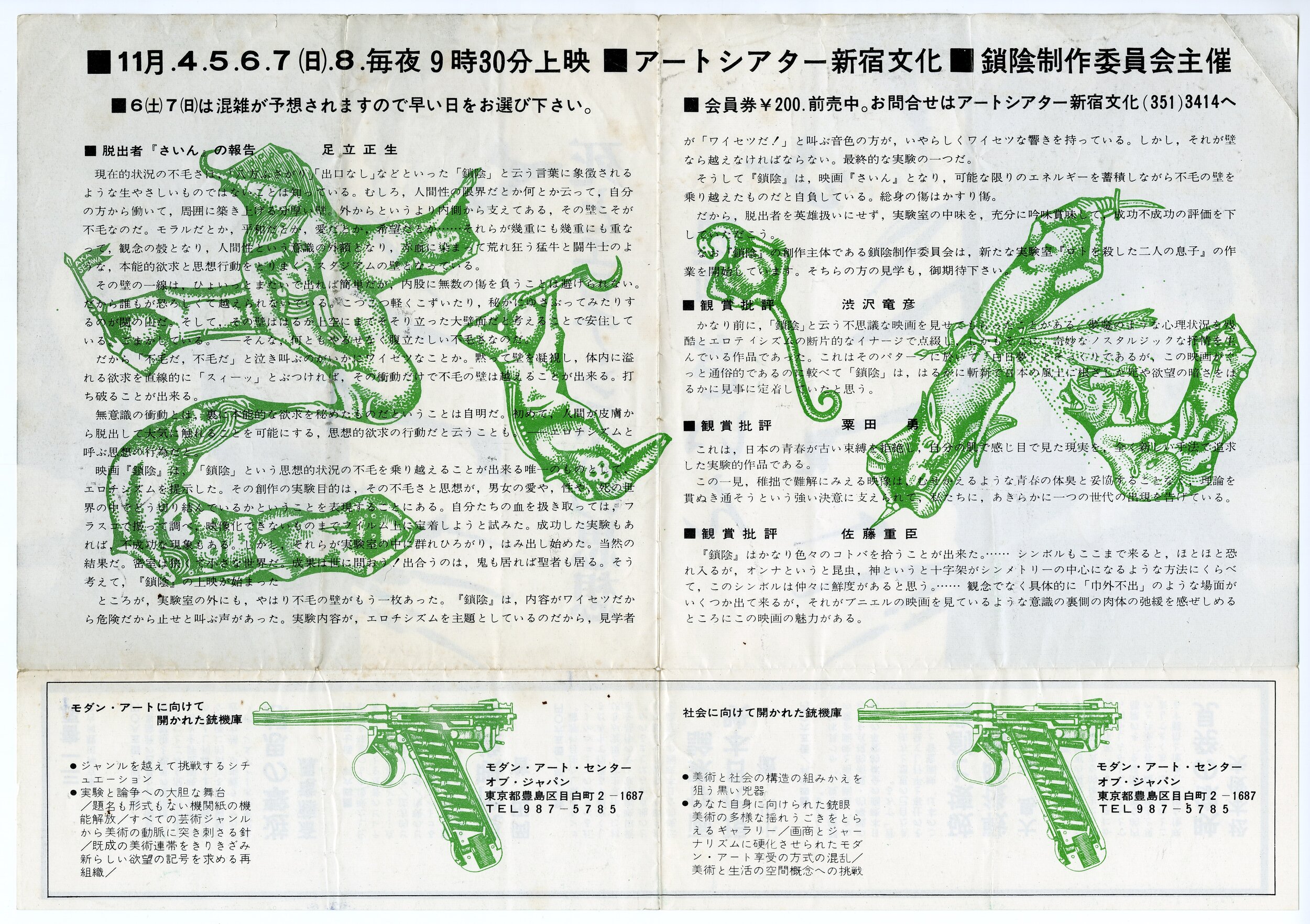

In May 1964, Masao Adachi’s controversial film Closed Vagina (Sain, 1963) was presented at the Sain Ceremony (Sain no gi), a two-day event in Kyoto that included a pre-event festival in which Sho Kazakura destroyed the venue’s piano and Genpei Akasegawa set fire to paper. During the festival itself, the film was set to be screened, but the second half of the film was stolen by the radical student group Hanzaisha Domei (Criminal League). However, Adachi screened the section that remained. When the post-screening performance began as scheduled, the audience crowding the stage was told that it had only seen half the film, and the venue descended into chaos and was surrounded by riot police. Revolving around a woman’s unusual sexual ailment, Closed Vagina was widely seen as an allegory for the Left; despite their vociferous protests, they were unable to defeat the Japan-US Security Treaty that was ratified in 1960.

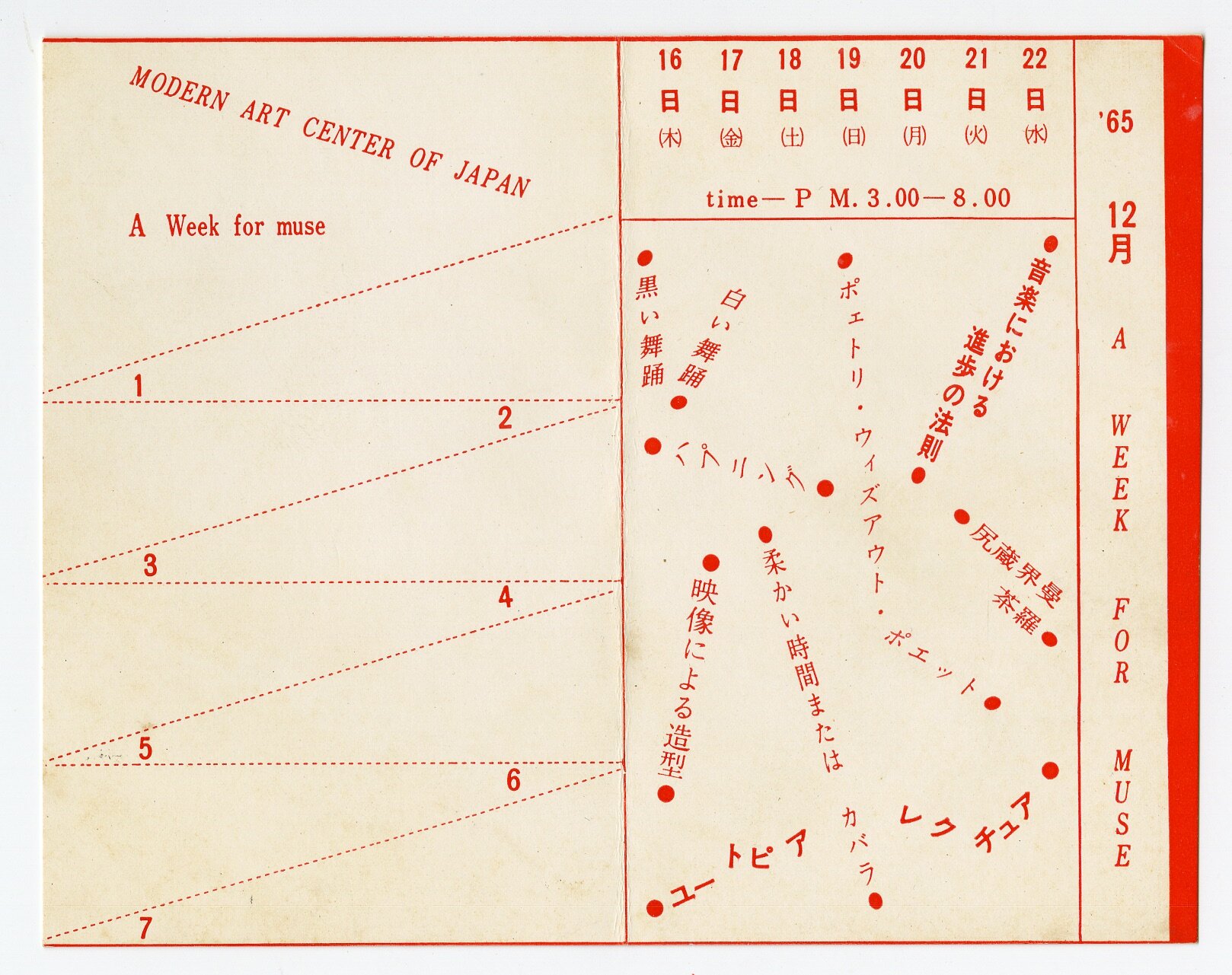

The film was also presented during Muse Week (Myuzu shukan, December, 1965) at Modern Art Center of Japan, organized by Yoshie Yoshida and included performances by Zero Jigen, Jikan-ha, Genpei Akasegawa, and Sho Kazakura.

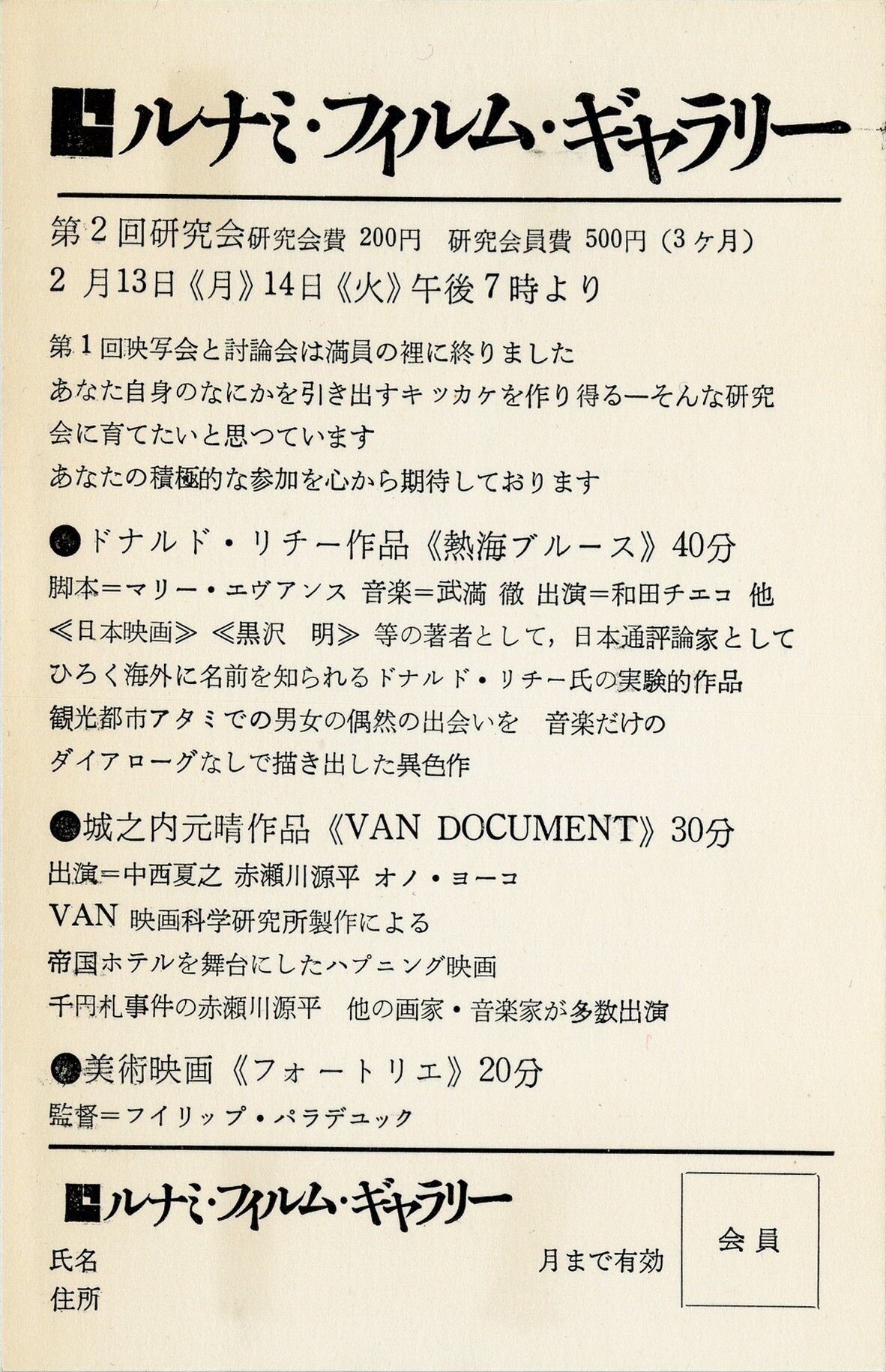

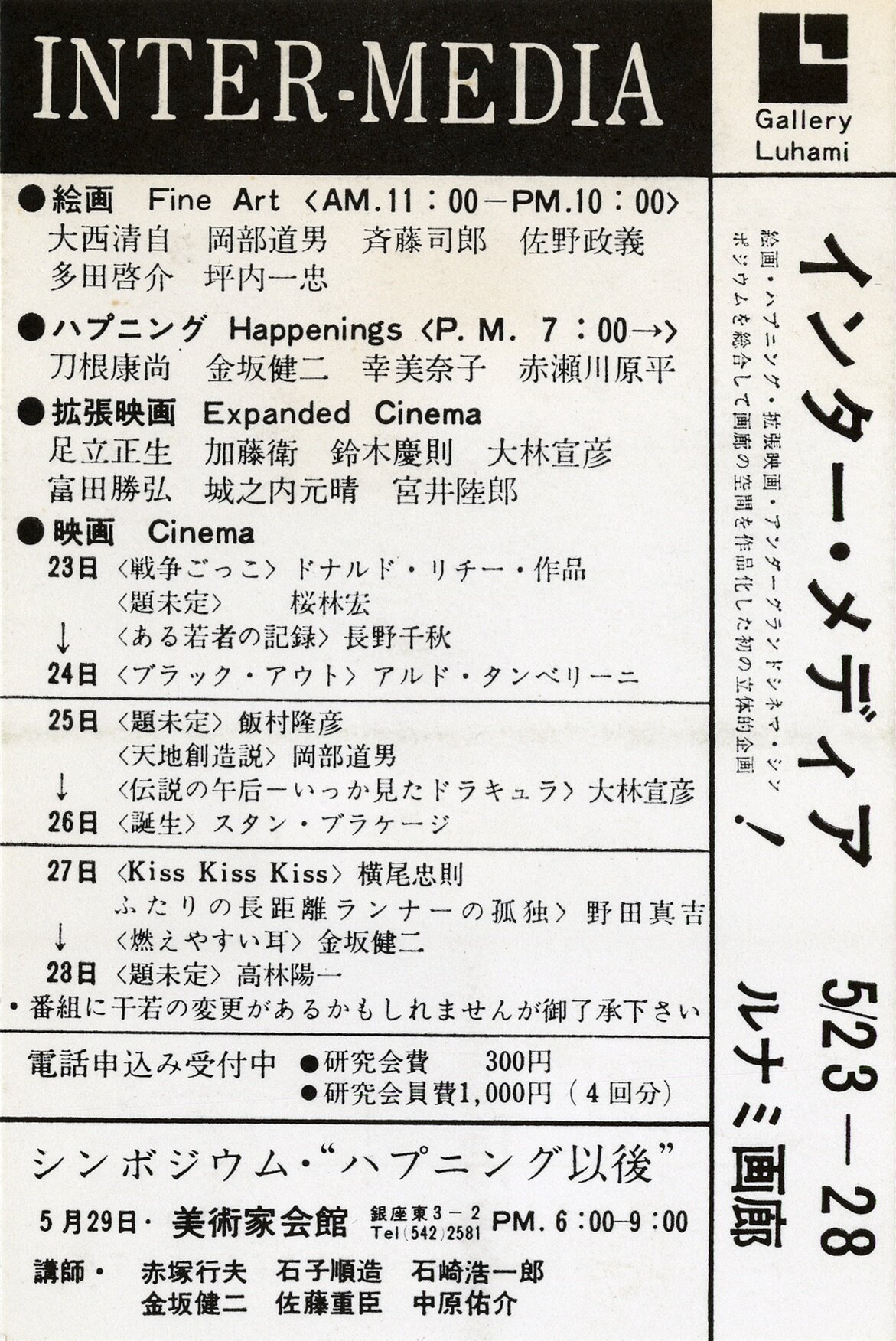

Intermedia

In Japan, the terms “expanded cinema” and “intermedia” were introduced, extensively discussed, and popularized primarily in film and art journals; they were inextricably connected due in large part to the fact that the film world played a central role in introducing them to Japan. Coined by Fluxus artist Dick Higgins in the 1960s, intermedia described work that was inter-disciplinary, straddling various mediums of art.

A seven-day event called Intermedia took place in May, 1967 at Lunami Gallery in Ginza, Tokyo. It was divided into five sections: painting, happenings, expanded cinema, film, and symposium. It was planned by critic Koichiro Ishizaki at the request of gallery owner Emiko Namikawa, and was an endeavor to expand the activities of Lunami Film Gallery, a series of experimental film screenings already being held at the same space. This was the first project in Japan labeled with the term “intermedia.” Jonouchi and VAN’s Hi Red Center Shelter Plan, titled VAN DOCUMENT was presented as a performance.

Hi Red Center Shelter Plan, 1964

Hi Red Center was formed in 1963 with the mission of staging “direct actions,” and went beyond existing concepts of a work of art, repeatedly staging events and happenings not only at museums and art galleries but also on streets, rooftops, and trains. Shelter Plan was staged on January 26th and 27th, 1964, in the lobby and room 340 of the Imperial Hotel in Hibiya, Tokyo.

Claiming to be acting on behalf of a fictitious organization called the Shelter Plan Conference, the Hi Red Center founders (Genpei Akasegawa, Natsuyuki Nakanishi, and Jiro Takamatsu) and Tatsu Izumi sent invitations and instructions to specific acquaintances. When they arrived, they had their height, weight, shoulder width, face size, interior mouth volume, and other measurements taken, and photographs taken from the front, sides, back, top of head, and bottom of shoes, generating data with which individual specifications were created for customized, one-person shelters. No shelters were actually created, however, and the series of events was the work itself. Involving not only visual artists affiliated with Neo-Dada and Fluxus, but also musicians, designers, editors, and others, Shelter Plan was one of Hi Red Center’s most ambitious actions.

Jonouchi and other VAN members documented the performance, folding into the footage photographs of Hi Red Center’s works prior to the Shelter Plan and footage of a bomb shelter. Presented first in 1966 as evidence to support Hi Red Center member Genpei Akasegawa in his 1000-Yen-Note Trial (in which he was accused of elaborately copying and distributing a 1,000-yen bill), then as a film performance entitled VAN DOCUMENT, the work blurred the line between art and life, while its use of techniques of repetition recreated the one-off nature of the Shelter Plan event, responding to Hi Red Center’s experiment in kind.

In 1968 the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Imperial Hotel was demolished due to a plan for reconstruction. Jonouchi directed his camera once again to this site, where Shelter Plan took place, and captured its disappearance in a fragmentary document. “The Imperial Hotel was the site of an event by Hi Red Center, but I was also captivated by the hotel itself, mysteriously entranced by it in fact. I filmed it several times, including in a state of collapse. When I entered its corridors, I felt just like I was entering the pyramids or something. I thought I was entering the heart of the city itself.” -Motoharu Jonouchi

Shinjuku Station, 1968-74

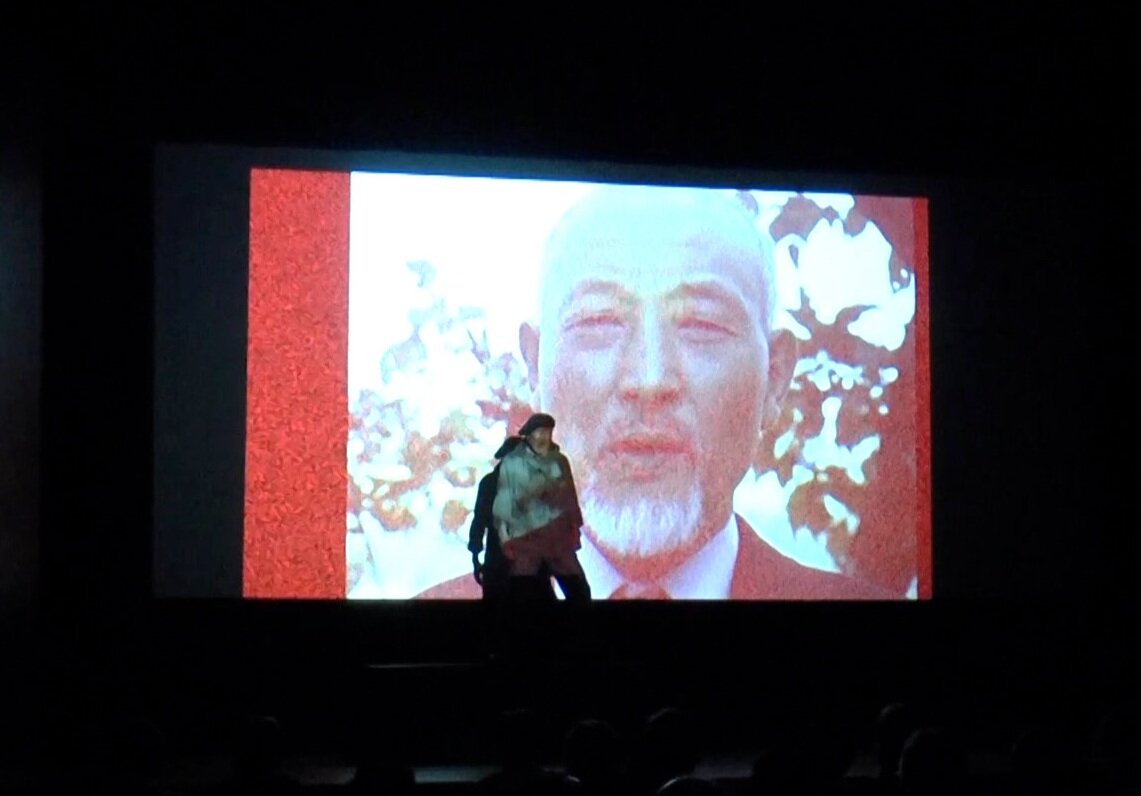

For Shinjuku Station (1968-74), Motoharu Jonouchi filmed himself reciting a poem in front of film projections of scenes from an International Antiwar Day uprising in Shinjuku on October 21, 1968. Kanai Katsu, who was loosely affiliated with the VAN Film Science Research Center, recalled the performance/screening of Shinjuku Station:

Jonouchi was dressed in what looked like a white safari outfit, and when he stood up, the first thing he did was forcibly screw [a flashlight] into the loop of his epaulet. He called out to me in his usual loud, clear voice, “OK, here I come,” switched on the projector, and strode purposefully forward. The projected film was black and white footage of riot police and student protesters. Jonouchi screamed out, “Station! Station!” as he marched toward the screen, and when he reached a spot where the film was projected on his body, he began reciting poetry he had written.

Fellow VAN member and collaborator Asanuma says that an endless, ever-changing, never completed cyclical work is what Jonouchi’s experimental process was all about, noting, “he stages a performance during or before the film, films that performance, and then screens that and again does a performance before the film, and on until it becomes an infinite kaleidoscope. This is one manifestation of what he describes as ‘the nature of all film lying in the generative process.’”

It’s virtually impossible to interpret Jonouchi’s practice in the conventional context of either film or art. However, when we experience his “works” outside of all such frameworks, they are not only intriguing experiments in Expanded Cinema, but reveal many new latent possibilities of film as a generator of one-time-only events.

Still from Jonouchi Motoharu, Shinjuku Station, 1968-1974, 15 min.

[Translated excerpt]

Station, station, station…

Goin’ Underground

Shinjuku Station

To the Koshu Highway

Agitation

A run-down café’s,

Action escalation

Aspirin and Pithecanthropus

Everyday Shinjuku!

The crying man’s station

The station roars, “Reign War!”

Katsu Kanai’s Poem of Far Yet

An homage to Jonouchi who passed away in 1986, filmmaker Katsu Kanai in Poem of Far Yet (Madamada no uta) remembers Jonouchi in his film and by reciting Jonouchi’s poem read in his film performance of Shinjuku Station (1968-1974). [The scheduled performance on April 1 was canceled due to COVID-19 closures]

Left: Bijutsu Techo [Art notebook] (October 1971)

Right: Jo-chan Ariki, Jonouchi Motoharu Kaisobunshu [Collected writings on Jonouchi Motoharu] (Tokyo: Shichigatsu-do, 2001)

keiichi tanaami

Interview with Keiichi Tanaami by Julian Ross, 2018. Collaborative Cataloging Japan, Edited by Neo Sora, Video, 25:55 minutes

During the 2018 CCJ Collection Survey of Keiichi Tanaami collection, researcher Julian Ross conducted an interview with the artist to learn about his expanded cinema works, the context for creating those works, and his views on presenting them today.

2018年に行った田名網敬一氏の映像コレクション・サーベー調査の際、研究者ジュリアン・ロス氏インタビューを行いました。現在ロス氏が進めているエクスパンデッド・シネマに関して、当時の様子や今日の展覧についてなど伺いました。

Widely recognized as a leading figure of Japanese pop and psychedelic art, Keiichi Tanaami is best known in cinema for his erotic, hand-drawn animations. As a young designer visiting New York City in 1969, he was amazed at the abundance of porn magazines at newsstands, so he collected pornographic images and made positive and negative reprographic prints onto transparent cel sheets, placing them on top of one another and twisting them in different directions to create a trippy, moiré effect, which features in several of his works. After projecting his illustrations onto the walls of the Tokyo discotheque Killer Joe’s using multiple projectors, Tanaami took an interest in Expanded Cinema. He describes the different possible layouts offered by the use of multiple projectors as being like a magazine spread.

This exhibition presents two works from his most productive year in experimental filmmaking: 1975. 4 Eyes involves the side-by-side, double projection of two prints with identical footage. One is projected a few seconds after the other, creating a slight delay to hallucinatory effect, which is further enhanced by halftone dots that expand and contract. A new restoration of Human Events—and its first presentation outside of Japan—is a film made as a backdrop for a dance performance by Kazuko Tsujimura, and involves six frames, each showing extreme close-ups of parts of the dancer’s body.

In 2018, CCJ organized a Collection Survey trip to Tanaami’s studio. The report informed CCJ to pursue a restoration project of Human Events, advised by archivist John Klacsmann. The end archival films were donated to The Museum of Modern Art. CCJ is pleased to present this work in More Than Cinema exhibition.

4 Eyes, 1975

Drawing from the culture of psychedelia and the discotheques he participated in, Keiichi Tanaami’s 16mm double projection film is comprised of images of printed material from which he enhances the halftone dots. Drawing from his experiences designing these clubs, Tanaami presents two prints of the same film in double-projection with a time delay, which suggests the mind slipping out of consciousness.

Keiichi Tanaami, 4 Eyes, 1975, 16mm transferred to video, double digital projection, 9 minutes

Keiichi Tanaami, 4 Eyes, 1975, 16mm transferred to video, double digital projection, 9 minutes

Human Events, 1975

A work with six frames, Human Events is a film made for a dance performance by Tsujimura Kazuko at Kinokuniya Hall, Shinjuku, Tokyo. The images are extreme close-ups of the dancer’s body, which is massaged by a finger as the color of the image changes. Arranged in a two (side)-by-three (down) composition in two films, different parts of the body are scattered in ways that defy the familiar order of anatomy. Having recently undergone preservation by CCJ, this presentation is shown as an installation, derived from new archival negative materials and prints. A true re-staging of the work will require live dance and music.

Keiichi Tanaami, Human Events, 1975, 16mm double projection, 5 minutes

Storyboard for Human Events (1975). Scanned reference material. ©Keiichi Tanaami. Courtesy of the artist and Nanzuka

Photo documentation of Human Events presentation, a work made for a dance performance by Kazuko Tsujimura at Kinokuniya Hall, Shinjuku, Tokyo. Scanned reference material Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Keiichi Tanaami and Nanzuka

Keiichi Tanaami, Human Events, 1975, 16mm double projection, 5 minutes

Storyboards and archival materials installation view

Storyboards installation view

Storyboards for 4 EYES (1975). Scanned reference material. ©Keiichi Tanaami. Courtesy of the artist and Nanzuka

Storyboards for Spectacle (1975). Scanned reference material. ©Keiichi Tanaami. Courtesy of the artist and Nanzuka

Archival materials related to Killer Joe’s

Tanaami Keiichi no Shozo [Portrait of Tanaami Keiichi] (Tokyo: Tanaami Keiichi Kenkyūshitsu, 1966)

12-nin no sakka niyoru animēshon firumu no tsukurikata [12 artists' way of making animated film] (Tokyo: Shufu to Seikatsusha, 1980)

Killer Joe's

Underground discotheques emerged in Japan in the mid-1960s, and became not only alternative spaces for exhibiting artworks but also spaces in which ideas about Intermedia art were put into practice. While artists brought their artistic aspirations to these sites, the spaces provided them with opportunities to rethink audience engagement and reciprocity between space, audience, and artwork. The club Killer Joe's was emblematic. Located in Ginza, Tokyo, the space opened in 1968 and featured ceiling, walls, and pillars covered in silver vinyl, which moved up and down in response to solenoid, geared motor, and air pumping devices hidden behind them. They were designed by filmmaker Rikuro Miyai, who described the panels as an "environmental skin" that would involve the viewer in an artistic experience. Twenty slide and overhead projectors were installed there to project Tanaami Keiichi's psychedelic illustrations.

KILLER JOE'S (September, 1968), first page of magazine, Scanned reference material

English translation by Colin Smith

Published September 1, 1968; Volume 1, No. 1; Published by Contemporary Art Circle; Editor/Publisher: Kaizuka Shinobu

“Open Sesame!” opens the door

A club for youth, bringing together the latest electronic technologies

An electric club based on completely new ideas is opening in Ginza.

The name of the club is Killer Joe’s. There’s something a bit alarming about the name, to be sure, but more to the point, every elaborate detail seems to be part of a bold, ambitious experiment hinting at the interiors of the future. Why is this?

For example––you find yourself standing in front of a door with a mural in the style for which Tanaami Keiichi is known.

The door has no knob, but neither is there one of those mats indicating that it’s an automatic door. To enter, you recite that famous incantation of Aladdin’s:

“Open Sesame!”

And of course, the door opens. Not because it’s a fairy tale or anything. With today’s electronic technology, that’s no difficult task whatsoever. Once you descend the stairs, you are baptized in a flood of moving images. All the grit and grime of everyday life are washed away, and you are reborn as a devout believer in the bizarre sanctity of this sacred pleasure dome. The space is dominated by softly curving surfaces covered with dully gleaming silver. One is hard pressed to find any of the square, boxy shapes we usually associate with interiors. Zones such as the ceiling, walls, and floor and not demarcated by the usual linear boundaries, and even the tables show nary a straight line.

The interior of the dome-shaped room is geometrically patterned and sometimes the entire surface changes colors, only to be filled with vividly colored flowers the next moment. At other times, the dome becomes a screen for 360-degree panoramic projection of psychedelic films. For example, a moving image of Marilyn Monroe may appear from behind the stage and gradually advance forward across the domed surface. Unfortunately it is not in 3D. The wall seems to be breathing deeply in and out. Close examination of the tornado-like pillar connecting the ceiling and floor in the center of the hall reveals that it is in motion, twisting around in a spiral formation.

All of these visuals and movements on the screen instantaneously respond to your motions as you dance, and to shouts and various sounds produced by the band of black musicians. It is, of course, impossible for an engineer to do this by hand––it is all performed by automatic controls.

Through these mechanisms, you feel you have expanded to the size of the entire room, have become one with room. Of course, not only you, but also the go-go dancers, the black musicians, and everyone else in the room.

This environment evokes the vast distances of space, hundreds of millions of light years, or the nostalgic feeling of being inside one’s mother’s womb. The room is an infinitely expanding and contracting microcosmos, which cannot unfold without your participation.

Say the magic words and the door opens. Your single step into Killer Joe’s makes the interior change and adapt to your presence.

We can say loudly and proudly: We (Yasuhiro Hayata, architect; Rikuro Miyai, filmmaker; Masashi Yanagisawa, electronic engineer; Keiichi Tanaami, illustrator; and this writer, Yasunao Tone) and our associates have gotten together every day in preparation for opening this place, exchanging ideas and collaborating. How do we transform a 265-square-meter space into a paradoxically non-environmental environment? Can we break free of the tired clichés of psychedelic discotheques and make it a place where all are free to play without divisions based on age, gender, or tastes and preferences? How can we make the stage, the seats, and the hall not separate elements but a unified whole, with mutual interaction among people in the seats as well as between audience and stage?

And how should we create the right kind of space for spending the discotheque’s business hours, from 5:00 pm late into the night? Consideration from all sorts of angles, as to whether these various factors were underpinned by truly new ideas that envisioned the state of things several years down the road, led to the determination of this structure. It features the world’s first membranous structure, with an interior entirely covered with patterns and images that can change instantaneously.

Finally, I must add that these would have remained ideas only, and never made it off the drawing board, without the backup we received from proprietor Mr. Tatsuma, who not only willingly accepted this bold and ambitious plan but also actively participated in formulating it.

([Yasunao] Tone)

Killer Joe Manifesto

We hereby declare that to survive this life of soul-deadening boredom, we will drown ourselves in love and liquor.

Who wants to die of boredom? And nothing could be more uncool than starving to death.

If we have to die, let’s die for love… or sink deep into a lake of liquor and meet our end at the bottom.

Despite one’s best efforts, it is impossible to get to know every single woman in Japan.

And considering the number of women in the entire world, we are destined to die having known only a tiny fraction of them. It’s enough to make us despair.

But compared to despair over war and peace, politics, or the limitations of one’s own talents, what sweet and pleasant despair this is.

As long as this despair is there, we will survive, pursuing love, chasing love, until we fall down exhausted with love and raise a joyful glass.

We study for love, march in protests for love, do back-breaking labor for love, and we would happily walk a thousand miles for love, never begrudging a step.

Thus, in the true Killer Joe spirit, we declare that this life of love and liquor is a gallant and magnificent one.

![Left: Bijutsu Techo [Art notebook] (October 1971)Right: Jo-chan Ariki, Jonouchi Motoharu Kaisobunshu [Collected writings on Jonouchi Motoharu] (Tokyo: Shichigatsu-do, 2001)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54f615cee4b082baf47cf92c/1585062389030-JGPLZ93QCOB9RC7LKSQC/200311_PW_010.jpg)

![Tanaami Keiichi no Shozo [Portrait of Tanaami Keiichi] (Tokyo: Tanaami Keiichi Kenkyūshitsu, 1966)12-nin no sakka niyoru animēshon firumu no tsukurikata [12 artists' way of making animated film] (Tokyo: Shufu to Seikatsusha, 1980)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54f615cee4b082baf47cf92c/1585149436274-UTC4I7UELS1O8ZSUQD9R/200311_PW_020.jpg)