Themes - Counterculture

The late 1960s is referred to as “the season of politics” in Japan to recognise a moment of near-concurrent anti-establishment uprisings across the globe, including France, Argentina, West Germany, Italy, as well as the United States and Japan.

In the United States, protest movements called for civil rights and racial equality, women’s rights, gay rights, environmental consciousness, and the end of the Vietnam War.

In Japan, student-led movements protested such controversies as the U.S.-Japan Anpo Security Treaty and, in solidarity with local farmers, the construction of Narita Airport. Amid this political milieu of social discontent, new forms of cultural expression emerged that channeled and contributed to these broader social movements. The embrace of individuality, experimentation, drug use, and sexual liberation led to the rise of the hippie subculture in the U.S., with their Japanese counterparts known as futen.

Cultural activity similarly shifted away from tradition to seek alternative settings from outdoors to discotheques; in Japan, the phenomenon was referred to as angura, short for the Japanese pronunciation of “underground” in reference to American underground cinema.

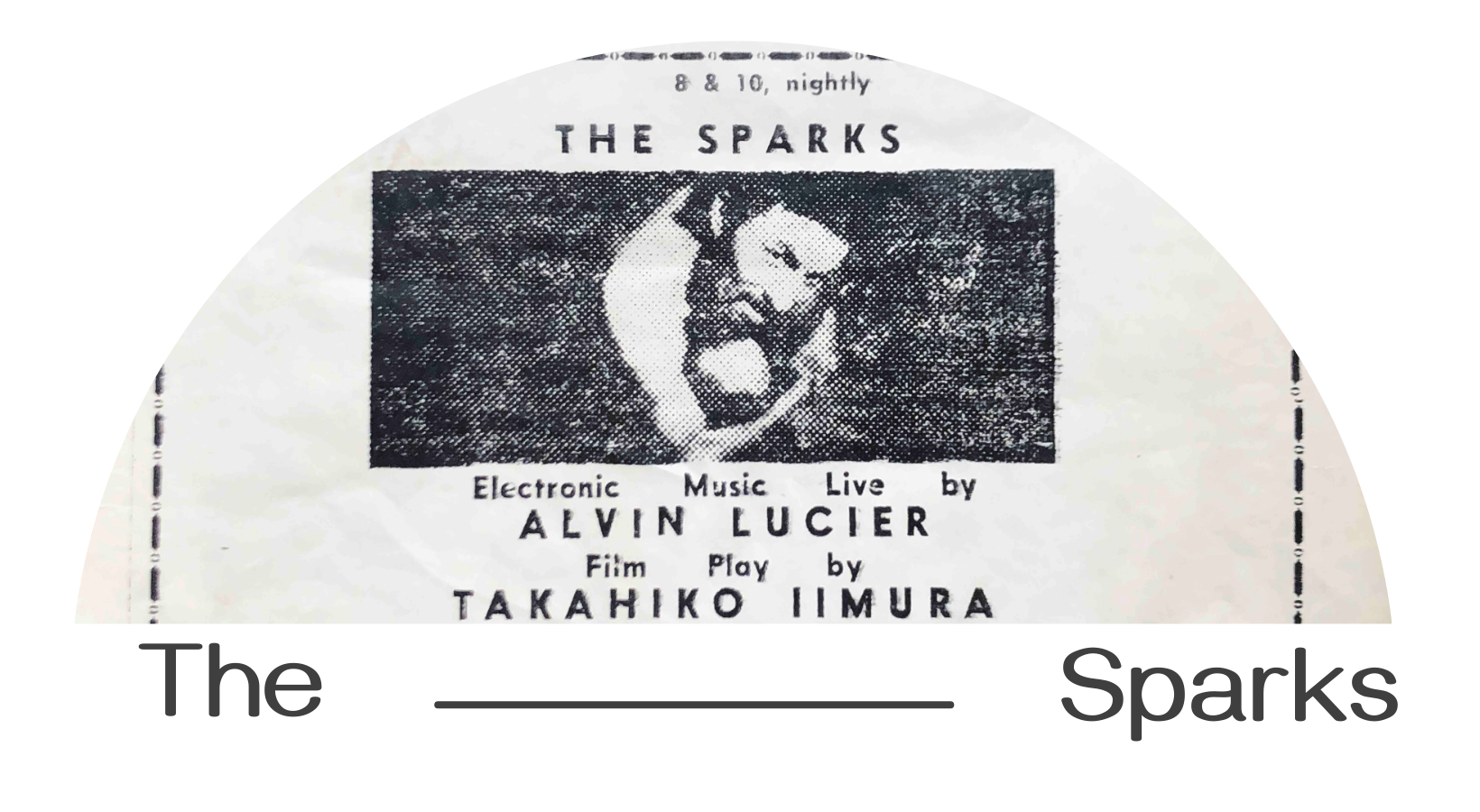

When Japanese artists moved to the United States, they participated in such social and cultural movements and positioned their artistic practices in response to them: Masanori Ōe joined the Newsreel Collective to document protests and participated in psychedelic shows with USCO; Takahiko Iimura and Alvin Lucier’s collaboration Shelter 9999, presented mostly in discotheques, was a response to Cold War hysteria; Mako Idemitsu filmed the feminist art installation Womanhouse by the CalArts Feminist Art Program; and Yukihisa Isobe played a key role in Earth Day celebrations.

Underground

Environmental Consciousness

Protest Culture

1960s and 1970s Lower Manhattan was a hub for avant-garde, underground subcultures. The cheap living cost of the area and experimental spaces cultivated a tight-knit community composed of musicians, artists, writers, activists, dancers, and film and video artists. Nightclubs such as the Electric Circus presented light shows, music, circus performance, experimental theater, and hosted the collaborative work Shelter 9999 by Takahiko Iimura and Alvin Lucier. New York was also the epicenter of the Fluxus movement, in which Shigeko Kubota, Yasunao Tone, and Takehisa Kosugi, among others, were involved. Over in Japan, these observations of experimental activities were digested, discussed, and practiced. Takahiko Iimura, Kanesaka Kenji, Donald Richie and others founded the collective Film Indépendent, in which non-members Yasunao Tone and Mary Evans also participated. Kubota, the Iimuras, Tone, and Kanesaka wrote and published about underground culture happening abroad.

Film Indépendent is a group for producing and screening independent and experimental films founded in 1964 by Masao Adachi, Takahiko Iimura, Nobuhiko Ōbayashi, Kenji Kanesaka, Jūshin Satō, Yōichi Takabayashi, Donald Richie, and others. This collective of independent filmmakers was primarily comprised of those who received a group award at EXPRMNTL 3 (1963) in Knokke-le-Zoute, Belgium. They also published a manifesto in Yomiuri Shimbun about “free cinema that breaks away from capital and industrial filmmaking.” The group organized a one-off event, titled A Commercial for Myself (December 16–17, 1964), but activities were infrequent thereafter.

Takahiko Iimura co-founded Film Indépendent and, as a young artist in Japan, collaborated with Yoko Ono, Hi Red Center, and others. He first came to the US in 1966 as a fellow of the Harvard University International Seminar in Boston, like Kenji Kanesaka. From that time on, he went back and forth between New York and Tokyo for much of his career. He became part of the New York underground scene with regular film screenings and performances, and reported on the scene back in Japan through articles published in periodicals.

Yasunao Tone was part of Group Ongaku, and involved with the Neo-Dada Organizers and Hi Red Center as a young artist in Japan. He moved to New York permanently in 1972, where he worked extensively with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, and performed at venues including the Kitchen, the Experimental Intermedia Foundation, and P.S.1.

Takahiko Iimura and Alvin Lucier’s work Shelter 9999 had numerous iterations, at least one of which was presented by the Sparks, a collective composed of Takahiko and Akiko Iimura, and Alvin and Mary Lucier.

Akiko Iimura met Takahiko Iimura through Shigeko Kubota. Before her position at New York's Japanese-language newspaper OCS News and as a translator, she also worked as a filmmaker and wrote articles for art and film publications in Japan.

Kenji Kanesaka came to the US through the Harvard University International Seminar, and also lived in Illinois while attending Northwestern University. He encountered iconic underground figures such as Allen Ginsberg and Andy Warhol, and through living in Chicago, captured his firsthand experience of American culture in the film Super Up. Depicting a young African-American character, the film is a critique of racial and class inequities, and consumerism, desire, and the police. He is said to have popularized the term “angura,” a Japanese abbreviation of the term “underground,” in Japan.

After Takehisa Kosugi moved to New York City in 1965, he collaborated with international Fluxus artists like Nam June Paik and Charlotte Moorman. A notable performance from this period was Kosugi’s Film and Film #4 (1965), involving film projected onto a screen which was gradually cut away, later cited as an inspiration by Hollis Frampton. When he returned to Japan in 1967, Kosugi founded the musical group Taj Mahal Travellers, an improvisational group that combined Eastern and Western instruments, electronics, and vocal chanting. They performed intermedia concerts in Japan, and also toured Europe and Asia in a Volkswagen minibus. Seiichi Fujii made Body Wave, a double-projection film featuring the Taj Mahal Travellers.

By 1970, both in the US and Japan, the serious environmental problems derived from large-scale use of pesticides, automobile emissions, oil spills, and industrial waste raised a new consciousness among the people and the governments to better care for the environment. Images of disasters, broadcast across the country, helped fuel a growing outrage over the state of the environment, especially among young radicals. In the US, organizers took inspiration from the anti-war “teach-ins” as a model to coordinate a national Environmental Teach-In, and “Earth Day” events began in various regions of the country. The first Earth Day took place on April 22, 1970 in New York. 250,000 people gathered on Fifth Avenue from 14th through 59th Streets, from Union Square all the way up to Central Park.

In Japan, the “Pollution Diet” convened in late 1970 to pass a groundbreaking set of new pollution-related bills in December of that year. The result of more than a decade of public pressure from industrial pollution scandals in Minamata, Yokkaichi, Tōyama, and Niigata, these laws were soon followed by legal wins by victims and environmental activists in the early 1970s. Such successes lead to a great deal of media coverage of Minamata victims, inspiring Nakaya Fujiko’s first video intervention, but also pushed grassroots environmental activists like Jishu Kōza to connect with the international environmental movement through participation in events such as 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (UNCHE) in Stockholm where they screened tapes provided by Nakaya.

Having obtained permanent resident status in 1966, Yukihisa Isobe was in charge of work related to organizing events in New York’s public spaces, at a time when then Mayor John Lindsey had unified the city’s culture, park, and recreation departments. Among the many events he helped organize was the Earth Day celebration where he mounted the Air Dome structure which housed discussions, music, film screening, and dancing. Impressed by Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome and the way of connecting architecture to ecology and environment, Isobe entered the seminar of Professor Ian McHarg at the University of Pennsylvania in order to study ecological planning, eventually writing his master of arts thesis about ecological planning for Hart Island as the site of a therapeutic community.

Fujiko Nakaya’s first forays into video in 1972 involved interaction and collaboration with protestors involved in holding Chisso Corporation to account on behalf of victims of Minamata disease. Yet Nakaya’s understanding of the problems of ecology were complex and structural. Writing in 1974 about why she felt it important to publish a Japanese translation of Michael Shamberg’s infamous DIY video handbook Guerilla Television, Nakaya draws a parallel between Japan and “Media America,” referring to the island nation as an “information-polluted archipelago” (jōhō kōgai resshima). In this single term Nakaya encapsulates her vision of the inextricable nature of media and natural ecologies, tying the pollution problems of rapid postwar industrialization and urbanization to the highly managed structures of the media systems that flourished in 1960s Japan.

Image: Brotherton-Lock, Courtesy of Tate, copyright Fujiko Nakaya

The anti-establishment movement gained momentum in the 1960s as the civil rights movement in the US made significant progress, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. At the same time, the intensification of the Vietnam War that same year spurred new anti-war protests that overtook college campuses and flooded mass media. Alongside these movements, other social tensions and awareness grew that addressed sexuality, women's rights, rights of people of color generally, racial segregation, and experimentation with psychoactive drugs. In Japan, protests in the 1960s involved demonstrations against the re-signing of the Anpo US-Japan Security Treaty in 1970, the use of Japan as a staging ground for the US involvement in the Vietnam War, the construction of Narita Airport, the upcoming state-sponsored Expo ‘70 and other centenary celebrations of the Meiji Restoration, and student struggles against university management. The spectacle of protestors clashing with authorities in the street became a recurrent topic of mass media images in both the US and Japan, and thus a frequent topic of artistic experimentation in the 1960s and ‘70s.

A founding member of the collective Video Hiroba that saw video as a technology for change, Fujiko Nakaya made Friends of Minamata Victims - Video Diary in 1972. The liveness of the medium was used to replay the actions of protestors at Chisso Corporation's headquarters back to themselves and create a new sense of their own power and autonomy through placing them on the television screen. Nakaya went on to document a fundraising rock concert with this same group of demonstrators, and sent some of these tapes alongside the Jishu Kōza Citizens’ Group delegation to the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm. A letter from the screening hosts at this event was printed in the first issue of Video Hiroba’s self-published journal.

Masanori Ōe moved to New York in 1965 and right away visited Timothy Leary’s psychedelic show where Allen Ginsburg and Richard Alpert (Baba Ram Dass) also attended. Ōe collaborated with the Newsreel collective, a group of filmmakers, photographers, and media artists who worked within and across mediums to provide alternative news coverage to the world events and anti-establishment movements at the time. Working with Marvin Fishman at Studio M2, he entered film production. In January 1967, the Human Be-In event was held, which focused on personal empowerment, communal living, ecological awareness, higher consciousness (with the aid of psychedelic drugs), and the leftist political consciousness. This event was followed by the Be-In in New York in April of the same year, which Ōe captured as the work Head Games. Another work, No Game, addresses the International Anti-War Day demonstrations at the Pentagon in October 1967, and incorporates footage taken from planes of bombings over Vietnam.