Community of images: Transmissions from the U.S.

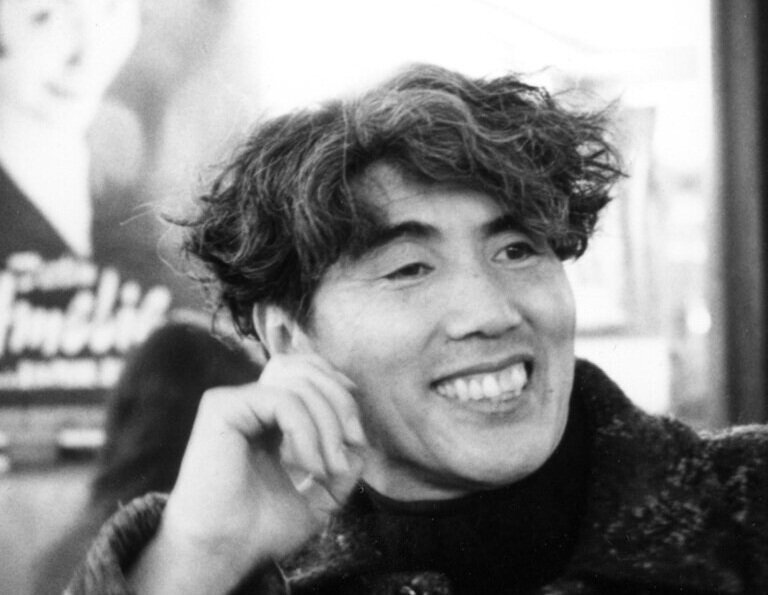

From Masanori Oe, Head Game (1967) © Masanori Oe

This August, we are pleased to announce the first instalment of an ongoing season on CCJ: Community of Images: Japanese Moving Image Artists in the US, 1960s-1970s.

Ahead of an in-person exhibition of the same name held in Philadelphia in summer 2024, we present a series of online screenings charting the array of moving image works created by the global Japanese diaspora over the last 60 years.

While our exhibition will focus on work created in the US or in collaboration with American artists and organisations, our August Members’ Viewing focuses on Japanese artists’ use of “America” - its pop culture, its media and its people - as a theme in their work, to which in the 1960s and 1970s, experimental filmmakers increasingly turned both a fascinated and critical eye. As they explored the politics, the eros, and even the utopian possibilities of this world of fantasy and fictions, the program presents three filmmakers' visions of the USA found in our online archive, the CCJ Viewing Library.

August Member’s Viewing

Kohei Ando, Star Waars! , 1978, 1:24min, 16mm Keiichi Tanaami, Goodbye Elvis and USA, 1971, 7min, 16mm Masanori Oe, Head Game, 1967, 10min, film transferred to video

Become a member for just $5 a month to access our monthly programs, and share your thoughts on our screenings with us via Twitter, Instagram or Letterboxd.

This Members Viewing program is supported, in part, by a grant from the Toshiba International Foundation.

The programs will be available for viewing on CCJ’s viewing platform.

Following the end of the Occupation in 1952, in the 1960s and 1970s both interest and resistance characterised the reception of American pop culture in Japan. On the one hand, as part of its global campaign of influence, the ongoing US grip on Japanese politics was the root of one of the defining issues of the period: the debate around the renewal of the US-Japan Security Treaty or ANPO, once in 1960 and for a second time in 1970, which sparked the long-running protests of the era. Coupled with the memory of the recent Pacific War and the ongoing war in Vietnam, Japanese and American countercultures were aligned through their mutual protest of American foreign policy and the media that acted as a vessel for it.

Yet although a symbol of political aggression, on the other hand, the US and its dazzling media apparatus presented a vision of a different society. Commodified sex, rock music, Hollywood, consumer culture - part of America’s intrigue lay in all the colourful appendages of the fascinating beast of capitalism; yet to progressive youth, it also promised multiculturalism and sexual liberation, new directions in psychedelic drugs, and a melting-pot of artistic experimentation in cities like New York. Young artists from Japan were drawn to the USA both as an object of criticism and as a field of exploration, and the topos of “America” and its pervasive impact elicited a range of artistic approaches, that renegotiated the concepts of influence, appropriation, collaboration and critique.

One example is the 1970s work of Keiichi Tanaami. Though a child in Tokyo during the firebombings of the Pacific War, Tanaami grew up obsessively watching American B-movies at a run-down local cinema, equally impressed by horror flicks as the performances of bombshell actresses like Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell. He then visited the USA in 1967, where he experienced what he called “an explosive culture shock,” witnessing the rise of Andy Warhol, the performances of The Velvet Underground, and going on to design album covers for Jefferson Airplane and The Monkees. (1) Goodbye Elvis and USA (1971) is an early example of his trademark gaudy, Pop style that constructs a vision of the US as a world of unbridled eroticism and consumption, centred around the totemic figure of Elvis Presley. Tanaami animates the cacophony of American iconography that flooded contemporary consciousness, from the world of celebrity to the images of warfare. While the plasticity of his hand-drawn animation turns the cold world of mechanical reproduction into a vibrant and erotic field of possibility, the film is also riddled with a images of violence. As art historian Jessica Morgan notes, the themes of Pop art developed in part in response to the spread of US cultural hegemony, and in given its political context, its particular mode of eroticism is often “tinged with the sinister threat of the unnatural, or even, in the omnipresent shadow of war, dismemberment.” (2) Tanaami’s animation, too, indulges exuberantly in the corporeal grotesque, redolent equally of the American body-horror films enjoyed in his youth - such as Tod Browning’s Freaks and Arnold’s Creature from the Black Lagoon - as the horrors of global conflict.

Where Tanaami tapped into the violent undercurrents of US media, others sought to document the acts of resistance that the media failed to show. Filmmaker and essayist Masanori Oe, as much a social critic as a utopian thinker, was deeply impressed by his time in the US, where he resided from 1965-1968 and created some of his best-known films such as the six-channel montage of US news footage Great Society (1968). Perhaps the biggest takeaway from his time there, however, came from the philosophy of the “flower children” of the Lower East Side in New York, with whom he lived at the time, and in whose way of life he saw a revolutionary potential. The culture of the hippies - its rejection of established modes of living, embrace of psychedelic experience, and imperative to “drop out” of what Oe called “the civilization of productivity” - is documented in his 1967 film Head Games (3). In the film, a demonstration against the war in Vietnam evolves out of a casual gathering of hippies, in which protest seems just another communal activity as natural as making art, dancing or playing music; its demonstrators united not only against a specific political agenda but against society in general.

And as American culture continued its worldwide exportation of music, films, and media franchises, in Kohei Ando’s 1978 film Star Waars!, an American media object is transformed from an object of mindless consumption into a medium for participation. Star Waars! is a mock trailer for George Lucas’ 1977 sci-fi blockbuster (itself inspired by the work of Japanese director Akira Kurosawa), starring a host of recognisable Japanese screen personalities. It begins with a recreation of the iconic roaring lion of the Metro-Goldwyn Mayer logo with the TV puppet Leon the Lion, yet the rest of the trailer teases nothing - instead, a string of celebrities simply echo the the feline mascot’s roar in various settings, in a wordless reverberation of the promotional apparatus that surrounds the original Hollywood film. The foil of the mock trailer is a mere frame to the real content: the infectious charisma of the Japanese stars, even in their non-verbal cameos. Ando’s film reflects a postmodern global cultural environment into which American culture has become so widespread that it acquires a kind of neutral status, ripe for appropriation, remix, and reworking with local inflections. In this environment, flows of cultural influence take on an elastic quality, and "America" is not an object of straightforward appreciation or critique, but a world of images that artists inhabit and explode from the inside.

program

Kohei Ando, Star Waars!!, 1978, 1:24min, 16mm

The 1978 release of George Lucas’ Star Wars (1977) in Japan and the attendant visit of Mark Hamill to the country prompted this mock trailer from Kohei Ando, which consists of a series of shots of Japanese celebrities from film and television who growl at the camera (literally, a series of star “waar!”s). Wilfully losing its object in translation, this charming pastiche reflects the complexities of global media dissemination and features actors Hiromi Go, Ikue Sakakibara, Tetsuya Takeda, Junko Ikeuchi, Haruko Mabuchi, Yoshiko Mita, Keiju Kobayashi, Kirin Kiki, Kiyoshi Kodama, Masao Komatsu, Chu Arai, Tetsuko Kuroyanagi, Yukari Itoh, Katusko Kanai, Kinya Aikawa, Midori Utsumi, Ikkei Kojima, and children's animated icon Leon the Lion. (4)

Keiichi Tanaami, Goodbye Elvis and USA, 1971, 7min, 16mm

Described as “an ironic critique of the powerful notion of America,” Keiichi Tanaami’s Goodbye Elvis combines animation and collage to produce a surreal, carnivalesque vision of the USA. (5) Hunks and bombshells, soldiers and superheroes, hot dogs, genitalia and war machines collide, transforming the landscape of American media into a psychedelic trip with Elvis Presley as master of ceremonies. The film is accompanied by an audio track of music and sounds played in reverse.

Masanori Oe, Head Game, 1967, 10min, film transferred to video

“How wonderful to drop out. You will live beautifully, with no need to work. You will be able to do what you want, anywhere you want, anytime you want, any way you want.” (6)

Masanori Oe defined the concept of the “head game” in his 1969 essay, “The Aesthetics of Ecstasy and the Yippie Revolution.” It is “the excellent philosophy of play” - an expression of rejection or “dropping out” of the “civilization of productivity.” His eponymous film, a collaboration with Marvin Fishman, is an experimental document of a demonstration against the Vietnam War, an event which seems to develop haphazardly from a recreational gathering of hippies. These “flower children'' paint their faces, blow bubbles and play instruments; they are later shown marching through the streets, handing out flowers, and burning an American flag. The film’s audio track - a jumble of political speeches, interviews with hippies, and comments on Vietnam - suggests a note of discord.

(1) Biography, Keiichi Tanaami artist’s site.

(2) Jessica Morgan, “Political Pop: An Introduction,” Tate Research Publication, 2015.

(3) Masanori Oe, “The Aesthetics of Ecstasy and the Yippie Revolution (1969)”, trans. Yuzo Sakuramoto, in Japanese Expanded Cinema and Intermedia: Critical Texts of the 1960s, eds. Ann Adachi-Tasch, Go Hirasawa, Julian Ross (Berlin, Archive Books: 2020).

(4) Wikipedia entry, Kohei Ando.

(5) Biography, Keiichi Tanaami artist’s site.

(6) Oe, “The Aesthetics of Ecstasy and the Yippie Revolution (1969).”

Community of Images: Japanese Moving Image Artists in the US, 1960s-1970s will be an exhibition of experimental moving images created by Japanese artists in the U.S. during the 1960s and 70s, an area that has fallen in the fissure between American and Japanese archival priorities. Following JASGP's Re:imagining Recovery Project and its mission to support and engage diverse audiences through Japanese arts and culture in collaboration with local organizations, this project aims to discover, preserve, and present film and video works and performance footage by Japanese filmmakers and artists to the wider public.

We have partnered with the University of the Arts, and will present this exhibition at the Philadelphia Arts Alliance in May or June 2024.