Interview: Ichiro Tezuka (VIC) (Hitoshi Kubo・ Yu Honma, English)

An interview with the director of the Video Information Center (VIC) Ichiro Tezuka, conducted by Hitoshi Kubo and Yu Honma on the 21st December 2016 at VIC Kichijoji Grankiosk.

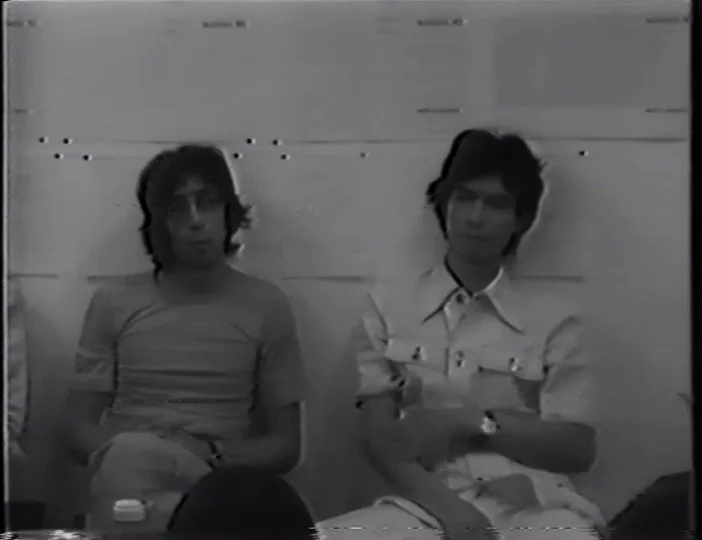

Interview: Ichiro Tezuka (VIC)

Ichiro Tezuka during the interview

In conjunction with our three-month online program of the works of the Video Information Center in partnership with Hitoshi Kubo and Keio University Art Center, we are thrilled to present a new translation of an interview with Ichiro Tezuka, director of the VIC, conducted by Kubo and Yu Honma. The original interview was conducted on the 21st December 2016 at VIC Kichijoji Grankiosk.

The notes inside [ ] are Kubo’s notes. The methodical ideals of VIC, that the videos “shall not be edited” have been honored, and in this interview without manipulation. This interview was first published in VIC File (Keio University Art Center, 2018).

Translation by Kwon Eugene

Tezuka (T): The other day, I was taking movies on the back streets using my iPhone. It’s interesting, isn’t it? It allows us to make movies in a characteristic way. I can easily do various things with it. I could throw them away all together, couldn’t I?

Kubo (K): Recently, people make films using their iPhones.

T: This is the pamphlet of the school festival of ICU (International Christian University). It shows what we had been doing.

K: Had you already organized VIC at this time?

T: No, not yet. It was the time when the ICU shōgekijō[ICU Mini Theater] and VIC were acting concurrently. I established VIC in 1972. This was my plan at the ICU shōgekijō [mini-theater]. An extra. The campus dispute was settled and the barricade which was set up by the university to not allow Kakumaru-ha (Red Army Faction, a revolutionary Marxism Group) to enter was taken away, that’s why.

K: Did the university set it up? Normally, I hear that students set it up. The university set it up to reject students with antisocial behaviour?

T: That’s right. We set one up again which the university did in the past. We were interviewed by Heibon Punch [Japanese cultural magazine]. It’s in here. The cover was 4 pages, saying “International Christian University V・I・C”. We set up the barricade in front of the church. At that time, we got excited, saying, “That excitement, once again.” Joking around, we remade this part only. So, it is only from this angle of view. I let someone draw it in Mr. Genpei Akasegawa’s style. Look at this, the concept on the barricade. I used to think about unnecessarily difficult things. At that time, I used to write the hard liners’ sentences.

K: “Gather and burn out what runs through your brain in a moment.” You are possibly consistent in this motif, aren’t you?

T: Yeah.

K: May I ask you what you had been doing before you established VIC?

T: I was a student of the International Christian University.

K: What were you studying?

T: ICU only had the college of Liberal Arts. In the department, there is “Social Science”, so at first, I was studying [Peter] Drucker, but it wasn’t interesting, so I moved to the humanities course, called “Humani” and studied the modern arts. As I have found my graduation thesis, I’ll show it to you. I used to think unbelievable things, I think. Like “Parallel Paranoia”.

K: That sounds interesting.

T: Basically, I was studying a kind of media theory in the end there. In 1973 or 1974, I think. It was very difficult to get over an idea once it takes hold of you you know? In short, it was the time when Whole Earth Catalog and Mini Comi(zines distributed among a limited number of people) were in fashion, that’s why. The gigantic pyramid-style, one way-style media wasn’t popular anymore. Participation-style media was in demand. One of these was video. The book titled Guerrilla Television was published, but I was thinking about the problem of bi-direction, or something which we could send out by ourselves.

K: Oh, I see. So, was 'parallel' about first thinking of an alternative to the pyramid structure of systems?

T: 'Parallel', in the context of media theory, means 'what does it mean to have two of the same thing?' That's what I wrote about. But having two of the same thing is already a contradictory idea because they're already in different places.

K: It means that having two of the same thing only exists in notions, right?

T: I was studying such difficult things, such as genetic epistemology by [Jean] Piaget and the concept of groups in mathematics. Marcel Duchamp was also part of it. Very, very hard, I was writing little by little every day in a coffee shop. So, I couldn’t get myself out of it once I began to think about it.

K: In contemporary art, were there any movements, artists, or specific works you were interested in at that time? Something that became a motif for your thinking.

T: Among them, the story of building 2 structures or 2 painted bronzes by Jasper Johns were my interests. Originally, talking about modern art, when I was in high school, I was doing some action painting. The reason was that my teacher was influenced by Taro Okamoto and Yuichi Inoue and he said, “Draw it standing on the desk!” I thought it sounded interesting. As I had been learning Sho (calligraphy) since I was a toddler, I knew about things like with how much speed or with how much weight, so I drew one with enthusiasm. It was when I was in the 2nd year of high school, I guess. It was a gigantic painting. I made my sister read the boxing scene in The Punishment Room [Shokei no Heya] written by Shintaro Ishihara and I drew it losing my mind. But it was wrong. I saw a book of paintings by Pollock at a second-hand bookshop in Utsunomiya in the Tochigi prefecture. And then I recognised that the method was completely different. (laugh) I had bashed it, using a small brush, doing it like this. His method was dripping. He used tremendous speed. When I saw it, I thought, “No way. I can’t beat him.” On top of that, I was seriously drawing on my own, so I was about to go mad. So, I thought it wasn’t good. I entered university and I joined a drama troupe, as I could do it together with others and I worked on the stage setting. They were performing Siegfried written by Giraudoux. I was an extremist at that time. “This is wrong, isn’t it? It’s a waste of time to make such shameful settings.”

K: When was that? After you entered university?

T: In the late 60s.

K: In the late 60s? It was a time for politics, wasn’t it?

T: Now I wonder how on earth could I do such a thing. The performance was for 3 days, but after 1 day, I had destroyed it. (laugh)

K: Do you mean the settings? (laugh)

T: Yes, the settings. (laugh)

H: You also destroyed that cardboard in the VIC tape, didn’t you?

T: I love destroying, I guess. (laugh)

K: What kind of settings did you make?

T: Later on, I changed it to an abstract wooden frame. I only remember that. Regarding the drama, I thought “Oh, no. These people are not good”, so I turned to directing. I did my best in Waiting for Godot written by Samuel Beckett. Putting up a tent, using the coffee bean bags in the school hall and I said, “It’s a bit uninteresting, so let’s create a scene of committing suicide by hanging.” During hanging scenes in the dark, I was doing various strange things, seriously. But I learned a lot. I received a lot of prizes for calligraphy. Because I was good at it. But it wasn’t interesting at all. I wrote many times with my teacher. I had been doing it since I was a toddler. But I didn’t know why it was good. I think it is the same in painting or other things. That’s difficult. There is no chance to look at myself objectively. I rushed into the action-painting without an object in mind. It was the feeling that I would do what I didn’t know. It was basically close to sports. I now understand it so well that I liked instantaneous things. I did action-painting at home, in the 8-tatami-mat room upstairs. As it is long, it went outside through the window. It was that long, honestly.

K: Did you draw on the scroll?

T: Yeah, on the scroll. I once exhibited it in the lounge at the university. Then a foreign woman came and said, “I want to buy it.” I said, “No, I wouldn’t sell it.” That was a good decision. I still have it. It is a bitter piece of memory from my youth.

K: You really keep this style, “Gather and burn out what runs through your brain at a moment,” don’t you? I think that “Gather” can include fixation, but you “burn” it out. You were creating your work, not only fixing but including burning it completely.

H: You said you didn’t understand it while you were writing, but the other day, you also said that you didn’t understand while you were videotaping, didn’t you? To me, the in-between of objectivity is very interesting.

K: You sound as if objectivity and subjectivity are always fighting each other.

T: My mind is all over the place.

K: (laugh) How did you direct a drama connected to the establishment of VIC?

T: Drama-wise, in theory, I was influenced by Masahiko Akuta from the Gekidan Komaba [a drama troupe]. However, I couldn’t record him on video. He had a very sound theory. I think that he created the word ‘homo fictus’ because the book Homo Ludens had been published. He had his cherished opinion: “In the eternal and boring, play around in the desert of time. Get over small chaos, using big chaos.” So, I started a little avant-garde styled thing by myself. In the basement of the university, a loud noise was generated. Vinyl was spread over the seats for the audience and a TV was set up. We were having a meal and a dog was present.. Although the dog barked woof, woof, the noise was even louder than that. There was a video in the audio-visual classroom. It is not the stop-motion which is all the rage right now, but in ICU, I could see that among the static people, a woman with some snow-white make-up went here and there and went to the library, then gradually approached the basement. At that time, I used video for the first time and I thought “This is easy.” In these circumstances, as I was a TV kid, I thought we should have a little more ordinary communication. Besides, the university didn’t function as a seat of learning at that time, so I created a curriculum called Saishu-shikou Koubou [Final Thought Workshop]. Inviting Toru Araki, Yutaka Matsuzawa and Kimiyoshi Yura. These activities became VIC.

K: Now this video in the avant-garde drama, were you aiming to record the drama?

T: No, not to record it. I used it as a part of the drama, as a tool. “Wow, I can use it.” So, I started cable television within campus, saying, “Let’s communicate more with TV.”

K: What was the catalyst to name it VIC?

T: I am a product of democracy, so I was enacting rules, using a mimeograph copy. I was in the 6th year at my university, so I gathered some freshmen. Then we created Video Information Center saying, “Let’s create a communication center using videos.” But the name was too long to fit it in a contract as it was created by students. Changing the name would give us trouble.

Honma (H): At first, you videotaped various teachers’ lectures and aired them on campus TV. You aired them and constructed cable TV. Is that right?

T: Yes, that’s right. The cable TV was airing in the lounge. The next cable TV which I aired was an Apartment Cable TV. At an early stage, the magazine Popeye covered us, though it was a very small article. The apartment had 5 doors upstairs and 5 doors downstairs. I named it PARAVISON TEN. The University Cable TV ended when I graduated from it, so I started an information center outside the university. I was doing it as media. For instance, there was an artistic way, linking letters in a town and watching only the letters. But I did Apartment Cable TV seriously. I penetrated the wall of the apartment house to insert a wire through it. We recorded a scene where we knocked on doors and asked residents, “Actually, we would like to do such a thing (cable TV within this apartment house).” But it was the worst. No one watched it, because all of us were at the studio. (laugh) There was nothing to do for us, so we relayed a broadcast of a shōgi [Japanese chess game] or anything regardless of what it was. I worked every day for a year and I got tired. I thought, “I can’t do it if I don’t earn some money.” After graduation, I worked a part-time job from 6 o’clock in the morning until 12 o’clock noon, loading geppei (sweets) into a car, there was a shop in Mitaka which was selling geppei, and I delivered them to Ueno and another, then I returned before noon. As I was free in the afternoon, I did my own work like video activities. I was never employed, not even once. At that time, my brother was drawing manga with Mr. Kumagai and they ran out of ideas. In those days, the baseball manga drawn by Tetsuya Chiba was popular, so we thought that “reality must be boring baseball.” Then they drew “Kusayakyu” (amateur baseball) .......

K: But you didn’t play baseball (in this manga story), did you? (laugh)

H: “The rest will be continued next” is written in that manga. (laugh)

T: There was no next. It ended after the first one. Fan letter, Kamirenjaku Mitaka-city, to Yoko Nakatsuka–that’s what’s written. I wonder if we were married at the time. She is there. She earned a good income, as a translator or an interpreter. ¥500,000 per month, at that time. I was like a kept-man. (laugh) It is an awful story, isn’t it?

H: But this is your brother’s manga, right?

K: Are those characters in this manga VIC members?

T: Yes, all of them. Mr. Kishio Suga’s brother, Mr. Yasuhiko Suga was also involved. Mr. Noyama, Mr. Uchiki, Mr. Ishii and me.

K: This manga is a documentary as well, isn’t it? It seems to be half fiction and half documentary.

T: Strangely, anti-romantic things were popular at that time and we were drawing as if to say, “We are boring as you see,” so it couldn’t get any popularity.

K: Was what you wanted to express unprocessed or raw? You mentioned anti-romantic just now. Did you think that reality appears in a different state from the processed one, right from the initial stage? For example, Waiting for Godot written by Beckett is a kind of realism, or anti-romanticism, isn’t it?

T: Yes, I agree. When I now read what Ms. Nakaya introduced in English when the Japanese video-arts exhibition was held at MoMA, I understand it very well. I only pressed the (video’s) switch without doing anything. It was a typical Japanese idea, when I think about it. It was written in such a way that it resembled Zen philosophy. The reason why it is an ultimately Japanese idea is that it is not a question of reality, but it’s just an existence. Nothing comes out from there. I did nothing if I did nothing. I just had to stay still. As I said previously, I only participated by pressing a button.

K: When I talked to you before, you said that many things which you weren’t aware of came out in video images, didn’t you? When you videotaped something, was there any trigger in your mind? For example, you wanted to keep this situation or you wanted to record it because something happened.

T: The videos taken by Video Information Center were records. The first record I took was Denju-no-mon ( Gate of Initiation) by Akira Kasai using a video camera. When I chose Akira Kasai, something was chosen. Then I went for filming. It was not the first time for me to use a video camera, but some people could recognize that I was getting tense when I shot such a performance for the first time. I thought, ”Oh, I can’t film it again.” It was interesting.

First of all, it is not like home-video. I had to catch the dance scene precisely. It’s interesting, isn’t it? It is a make-or-break game.

K: What kind of system did you use?

T: An open-reel named Portapak and a camera from Sony. The previously mentioned PARAVISON TEN was related to Ms. Nakaya and people from Video Hiroba [Japanese video artist group] and we filmed in New York and aired there (in Japan). The recorded tape we sent was of the street in front of the apartment house named Kojiyama-so. We kept recording everything.

K: How long did you record?

T: The tape lasted for 30 minutes. When a car went towards me, I had to duck and avoid. (laugh) I think that was interesting. Some were sent from New York. The video of Talking Heads by CBGB at the live house was sent to us. That was great, wasn’t it? It had a feeling of punk. Johnny Rotten was there. Mr. Midorikawa in our group used to have many small Punk rock jackets. I copied them, placing them all on one paper and titled it “God save the punk” and then we ordered a printing of it at Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd. even though we were just students. They were sold at a record-shop for ¥1,000. They made a good sale. The other day, I enlarged it. People from that time saw it and said, “You have been creating such a valuable thing.” Well, it is an Information Center after all, showing that, “We are doing it like this now.”

K: You mean that it was a Video Information Center, but the video wasn’t always the method of communication, right?

T: At that time, I thought that making it and keeping it was valuable, so I did.

K: It’s a Video Information Center, but more stress was placed on the Information Center. Is that right?

T: You could say so.

K: Oh, I see. Actually, the main media was video, but did you mean the activities such as sharing, sending or recording information were more important?

T: Yes, they were some of it. Nobody had been doing record-filing systematically. There were some people who recorded a little. People who were working with me seemed to think, “Probably, this could make a lot of money.” I never thought of that, though. So, I might have been told, “You deceived us.” (laugh)

K: A while ago, you used the metaphor of pyramid-style media system. Have you thought about the alternative of a pyramid-style system like NHK and other major broadcasting TV stations as the nation’s armed forces? And yours was a reserve force or a guerrilla?

T: There were many things which NHK never filmed and never kept as moving images. A person from NHK came to collect the television licence fee. NHK has a good system, in terms of content. I said, “If you let me appear on TV, I’ll pay you.” He never came back. (laugh)

Ichiro Tezuka and the VIC office around 1980

K: How did you judge TV at that time? What was your favorite program?

T: I was in the countryside, Tochigi prefecture. One that impressed me was when Ushio Shinohara appeared, with his Mohican hairstyle. Mohican with a bridge was put in the paint in a bucket. He shouted on the street, saying “Wah!" (and he painted his work). “Wow, there is a mad man in Tokyo”, I thought. Another one was on the NHK Channel 2, Yukio Mishima appeared and I listened to his talk. I thought that he sounded very intelligent, but the way he talked was defensive and sweet. I remember that I thought, “This is fantastic,” as if TV was everything.

K: Was it a feeling that you could make a TV program by yourself?

T: Yes, yes. “Such a thing can be done.” “It can be done quite easily.” I thought it was the achievement of Sony.

K: How did you collect other members of VIC? Were they people who did theater projects with you together for instance?

T: Nobody had experience in theater.

K: Oh, really? Only you?

T: The ICU shōgekijō received a club-budget and it created the Video Information Center. Sounds awful, doesn’t it? To use the budget like that.

K: At first, it seems like it didn’t go well. Did you recruit members?

T: That’s right. I persuaded them.

K: What kind of story did you tell them when you recruited people?

T: Like I’ve just told you. The usual communication didn’t go frankly like TV. Kakumaru-ha (revolutionary Marxism Group) and Chukaku-ha (revolutionary communists) are enemies. There is no other way apart from fighting. They couldn’t communicate because of a preconception. I wanted to have normal communication, taking more time. Then I asked a priest, Mr. Furuya, “I really want to do this project, but I can’t afford to buy any video equipment. Could I possibly borrow some money?” He lent VIC some money.

K: When the students’ movement was at a peak period, at that ‘time of politics’ [referring to the 1960s], there was a situation that people judged by a preconception of each other’s ideology. Under those circumstances, how did you think about your own ideology, the times and the political problems?

T: Speaking of ideology, I am the son of a merchant and I was brought up by my grandmother from the Meiji period. My grandma had been running a shop, named Tezuka Suppon [snapping turtle], which had been selling the lifeblood of soft-shelled turtles. It was a unique shop. Using pliers, make pit viper’s powder like this and then blend it in the coffee-mill. “Here it is. It’s ¥3,000.” It is very realistic. I probably understand their [people who think they can solve problems by discussion] feelings, but when it comes to fighting, I have to win. Attacking American troops, using a broad-bladed kitchen knife? –Self defence? – It’s out of the question. People at that time discussed things democratically, didn’t they? What can you do by persuading? As there was an atmosphere which gave you an impression of an understanding if you had talked, they were in a mass bargaining period. But take the son of a merchant, I think if he had wanted to change things, he would have joined the National Defense Academy of Japan with others silently, and one day, he would have staged a coup d’etat. When staging a coup d’etat, you shouldn’t stand out like Mr. Yukio Mishima, should you?

K: You were completely realist, weren’t you? You were realistic as well as extremely practical.

T: When I watched Juro Kara and Hijikata at that time, almost all their communication was aggressive. They were only provoking a fight. I used to be strong-willed against any type of people as long as I had that type of aggression.

K: The motif of VIC that I heard from you earlier, while on one hand you want to change things little by little through discussion and having very close communication, on the other hand it feels extremely practical.

T: I think that politics and society is basically like that. As I’m a merchant and I’m speedy, it doesn’t suit me. There was a female student who was 3 years older than I was and was a member of Kakumaru-ha (revolutionary Marxism Group). I respected her. She told me I should decide on either joining the group or doing theater. I thought hard about what I should do. Then I decided to join the theater troupe, as I thought I couldn’t win, even if I fought with an opponent. I wrote novels and a summer thesis related to arts when I was in high school. My teacher said to me, “You are extremely argumentative. You should go to the department of aesthetics and art history which has a lot of controversies at the Tokyo University of the Arts.” But I thought it wasn’t proper to do something when I was not sure if people needed it or not, just because I had to survive.

K: It is amazing. I think that is your parallel thought. On one hand, you do action painting on a scroll with your tremendous spirit, on the other hand, you can think of your life in practical terms.

T: If I had been doing those sorts of things [painting on a scroll], I wouldn’t have survived.

K: But there was a possibility to take that direction, wasn’t there?

T: I couldn’t be that stupid.

K: You didn’t mean to choose one of them, but to do both at the same time. Is that right?

T: I want to make an “Eating Museum.” Human beings have been alive, eating things all the time since a long time ago. Can you believe it? People have been eating all the time. Recently, I started thinking, if people can survive just by eating, other things, such as difficult countries, ideals or beautiful things do not matter. I have come close to Buddha’s philosophy these days. (laugh)

K: Are there factorssuch as delicious or not delicious in this “eating”?

T: No, it is all right if I eat and survive.

K: Any other things? For example, it is said the basics of life are clothing, eating and living, but what do you think about “clothing”?

T: It doesn’t matter. But I wonder why mankind started wearing clothes? People are weird. I think people are freaks.

K: How about “living”, “to live”?

T: In a talk by Mr. Takeshi Yoro (an anatomist) and Mr. Kengo Kuma (an architect), Mr. Takeshi Yoro asked, “In what kind of place can people live?” Mr. Kengo Kuma said, “Wherever you go, you can live.” That’s true. He was investigating small villages in various places in Shuraku-no-oshie (teachings of a village) together with Mr. Hiroshi Hara, wasn’t he? He was watching it and it influenced him a lot. If you don’t eat, you will die. To junior high-school students who are worried, I say, “If you eat healthily and survive, other things do not matter.” But they seemed not to understand it. It’s strange. When I started VIC, I read Whole Earth Catalog and learned some ideas like [Spaceship Earth] by Buckminster Fuller and the “Global Village” [Marshall McLuhan]. When I look back, videos are slightly closer to those ideas in those archives. [The idea that] you can understand the world if you read through this encyclopedia I don’t think so. The idea was if you read this, this is the world. The idea itself is too old. One time, when Kakuei Tanaka (the former prime minister) made an effort in mass production, there was a policy that the world would become more prosperous by creating freeways. But when that kind of era finished, the idea to understand a world in one category like a museum became nonsense. Buddhism doesn’t say such a thing. It can’t be helped to deny myself who has been doing the same thing though. Maybe, it will never change a lot.

K: Have you got anything which especially has been in your memory of VIC’s activities?

T: The most disappointing thing was that I couldn’t record the peak of Jokyo Gekijo [the Situation Theatre] run by Juro Kara. As I experienced a drama, I found out that I didn’t understand the concept at all, even if I read the script of Koshimaki Osen or even if I saw the performing site. So, I wanted to film it. At that time, there were many people who asked me why I had been taking videos. Because the drama was acted on one occasion and quite a few performers put all their energy into it. Akira Kasai was one of them. They didn’t understand recording, filming and keeping. Therefore, I couldn’t film it.

K: At that time, was recording regarded as an unattractive thing?

T: Yes, ugly. They said, “Why did you do such a thing?”

K: Did they rather cherish the singularity of the performance?

T: But, once they accepted the recording, they became selfish. “As we are having a performance in New York, prepare everything in U-matic.”

K: They began actively asking you to record it.

T: Yes, they did. But Shuji Terayama from Tenjōsajiki (drama troupe) accepted filming from the start and he was going to Europe. His stage had no color, except pitch dark, but he made it brighter for videotaping. And then Juro Kara became gradually similar to him.

I planned the information museum, “Soft Museum”, asking Ms. Nakaya, Mr. Yusuke Nakahara, Mr. Ichiro Hariu and Mr. Katsuhiro Yamaguchi to be judges. Ms. Nakaya took me to several museums and galleries and when I suggested to the deputy director of the Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts, “Would you like to do the Soft Museum’s plan?” The answer was, “No way. It’s too early.”and “Come back you to Tochigi and you should become a curator in our museum.” I responded, “Are you joking? I don’t like Tochigi. I’ve come up to Tokyo from Tochigi.” He was Mr. Seiji Oshima.

K: The idea of the “Soft Museum” is conveying things to future generations or conveying things to people of the present, I think, but did you have those sorts of ideas, such as conveying what you recorded to people in the coming ages as a history or showing it to people overseas?

T: In short, let me put it this way: “There were things which I didn’t understand if I didn’t film a video.” But I thought it wasn’t right to collect all the images from the CCTV in Shinjuku Tokyo, so I skipped time. When I imagine that some people will see it 100 years later, a smile comes on my face. There was the idea of, “Have you understood anything?”(laugh) Now, everything is computerised and information spreads all over the world in a moment just like a “Global Village” but nobody has been doing it skipping time regarding the information from museums. I had wanted to see how the recorded videos worked in time, but the video-tapes went moldy and became useless. Sony, Panasonic, Victor and Fujifilm were all advertised a lot on TV for filming weddings or children’s events, but all of them have become useless now. It’s fraud, isn’t it?

K: We have often heard, “Let’s keep a piece of memory” as a catch-phrase.

T: Neither weddings nor anything else will remain. Equipment has disappeared. I think it may be interesting to think about time a little more.

K: TV can make a difference in time, but TV has been pursuing real time and now it has been broken into pieces, hasn’t it? No matter where you are, you can see moving images on CCTV if you hack it. We can send our 24-hour-lives from the camera on PC. Under those circumstances, if you record them and stock them somewhere, there is a possibility to see them 100 years later, isn’t there?

T: Just like corroborating photographs on the site, “What was it?” and when you have a close look, just like in the film Blow Up by Antonioni, it was a murder scene rather than a love scene. There is that kind of fun, things which you can’t see but which were recorded.

K: What do you think about this? For example, 800 million people record their own lives, and edit them. The amount of data is enormous. Who would see it, for whom was the record and what is it for?

T: Eventually, there is no other way but to accept that being anonymous is fine. Because when one decides to film something, editing has already been done. Everything improves with IT... I believe that people who don’t call are rude. Do they finish everything by e-mail, I wonder? People tend to have belief in understanding virtual reality. Because a small part of sensation is working in virtual reality. Video which used to be called a new media couldn’t be a substitute for reality. We are living in an exceedingly irreparable time, aren’t we?

K: For example, it is similar to playing house, the training equipment of real communication. It has some aspects of educational equipment for infants. On one hand, it has the factor of being a very convenient tool to access information. Not all people shut themselves off in their own reality there, I don’t think. Technology ensures the quality of distance and it establishes what distance the distance is. Therefore if it means that choice is increased, it could be so, but what you place in reality may depend on each person.

T: I’ll tell you, telephones or IT would disappear if electricity disappears. (laugh) Unthinkable things will happen.

K: Talking about strong media like paper, the amount of things can be quite an amount of information. But the merit of digital data is compression. But the higher the degree of compression, the weaker the media becomes. It’s an opposite process.

H: I have a lot of compressed digital files which I can’t open.

T: As you are in the field of enormous information, you get lost as to which one will get caught in your sensor. It is just like an encyclopaedia. You are trying to control the information not as a paper but put it on the paper? That idea… well, I have begun to sound like a critic.

K: The thriving time of digital media corresponded with my student days. If everything can be replaced by digital data, the books written in the past and the books which will be written in the future are all in binary code, so they can all be simulated. The newer the technology is, the nearer the typical utopian ideology is to being embraced, isn’t it? The 1970s is exactly the boundary of the era and you started from that era, didn’t you? It is exactly the boundary for technology as well as for the arts.

T: In my thesis, I did such a thing and then I was trying to do something in media. Eventually when I expand or copy the sensor of my single body, the destination is my life-sized self. It’s a Songoku’s (the Monkey King’s) world. No matter how hard you work, you only understand what you can understand. You can’t understand what you don’t understand. I can’t help having that feeling. But generally speaking, there is a boom, as media and TV have been managing to spread the information. The information is now integrated into that sort of place. It is not the right answer, though. Business needs to catch the tendency as well. I was a television child. So I love entertainment, scandals, “wide-shows” (TV talk shows) and many other programs.

K: Even now, do you often watch TV?

T: Yes, I do. When I watch a “wide-show”, I watch it seriously, thinking that if I can’t see the truth here, I won’t ever be able to see it. (laugh)

K: Even when you watch TV, do you have a desire to get to what’s behind it? Always?

T: Not exactly what’s behind it, but I watch, thinking, “What on earth is happening?” “It could be untrue.” I’ve got such a feeling to some extent. It’s a thing in front of you.

K: You want to make sure of the fact.

T: Yes, quite often. I like such a thing without participating.

K: It is related to filming videos. On your name card that you gave me, VIC is written. This name has been continuing, hasn’t it? You have been filming for a long time, doing Apartment Cable TV, the workshop at Parco and Video Station. Your activities are diverse.

Did you have a trigger, regarding this period of transition?

T: “It’s much better to film this,” is my thought. But people started filming because of the spread of video equipment, so I don’t need to film deliberately. People haven’t realized what will be interesting in 100 years’ time. I think there must always be something which needs to be recorded. Most people have been videotaping ordinary things, so I’d like to film something which doesn’t make sense, even 100 years later.

K: That sounds good. (laugh) In order to recollect one’s memory, to trace the social feeling at that time or to see something in a fresh light, filming sounds great. People want to film everything which they know. Recording is the same, isn’t it? The objects are influenced by one’s preconception.

H: Besides, the subjects of photography point out the direction, as if it says, “Take an image here.” Instagram is popular currently, so, “This is the subject for taking a picture,” stands out more than before. Of course, they were there in the past as well.

K: Adding to that, people don’t film unprocessed and fresh things, for example, the picture of what you are eating halfway through. Most people tend to take pictures which look fashionable or cool. The main purpose is not for the eating but “showing one’s cool life” as information. It’s a totally different style.

H: When people take pictures and moving images, they definitely think about showing them to someone. Of course some people are not always like that though.

K: So, they are not thinking of showing them to people in 100 years’ time, but to people who are connected to it at this time.

H: In a sense, most of them are trying to look their best.

K: Did you, along with the first half of VIC’s activities and its present activities, for example, do the activity of revitalizing the community, mediating in the community in Kichijoji? The story of the backstreet (yokocho) sounds like the continuation of your activity from the first stage.

T: The catalyst for starting something relied on the thought that nobody had done it, it seemed to be more interesting. As I’m a warped person, I absolutely hate to do the same as others. When people go a certain way, I’ll never follow that. “Off you go.” It may be from Kitarubeki kotoba-no-tameni (For he Coming Words) [a photo-book] with photographs by Takuma Nakahira (photographer) and The World of Blur and Bokeh photography by William Klein, but becoming Bokeh might be a different expression. Many photographers want to take fresh images, but it is difficult. Most of the time, they only take the familiar sceneries and the collection of them is so boring. So, I got bored. There are no surprising pictures recently, like “Look!” at the first glance. Don’t you think so?

K: Both creating Harmonica Street in Kichijoji and running “PARAVISON TEN” mean positively mediating in the community, doesn’t it? The methods are different, but they are similar. What do you think about its continuity?

T: I seemed to be in charge of spreading Sony’s videos. In a sense, I did it thinking it was for Sony’s sake. Then I started thinking it hadn’t been good. Gradually, I came to hate my idea that I could make Sony pleased to offer some money to me.

K: When was it?

T: It was the late 1990s. But I was tired of it and started running a yakitori restaurant (grilled chicken skewers). I felt very free, as I could do what I wanted to do instead of selling what someone made. It didn’t need any sponsor.

K: Making a backstreet means making a community, doesn’t it? “PARAVISON TEN” at the apartment house was also making a community, using a cable TV, wasn’t it?

T: Do you think it means making a community? Speaking of making something, the smallest TV station in the world sounded interesting. People might be surprised, I thought. That’s the reason for making it on a backstreet. Creating a vacant lot just like a White Cube of museums and then building a structure which is supposed to be interesting on purpose on it, like Roppongi Hills, can’t be right. I’m quite certain about it, as I used to practise calligraphy. The backstreet was originally a black market to sell rice illegally after the war and it has led to the present one. It couldn’t be created systematically. When I had a close look at the backstreet, each person did their own thing respectively, making shelves or eaves, not working together in a group. They were moving on a small scale. The good point of a backstreet, after thinking about it for a long time, is that, “It is small”. We men can understand it very well, but if I talk to a woman, for example if you and I are 5 centimeters apart, a different function starts working in my head. A “narrow” space can bring a physically different communication. The most important thing is, the reason why I started talking about such a thing is that the rent in Kichijoji was expensive. It was a problem of property. That’s why I wasn’t free. So, the smallest space was chosen, like the project to build 50 houses for the rent of ¥50,000. It is shapeless and the smallest space. These small spaces originated Japanese tea-room culture, right? I don’t understand it, though.

K: It creates tension and is intimate.

T: With Japanese-style, “See, it looks cool,” I don’t like those sorts of things. In short, I understand it’s good sense, but I think, why can’t you do that in a more carefree way?

K: Do you mean you prefer it much noisier?

T: You see, I’m provoking a fight. When I worked with Kengo Kuma, titled, “Enemy is in Rikyu (expert in tea ceremony of Sengoku period).”

K: (laugh) Why?

T: Because he tried to look nice. Things like good manners or beauty seem to be too pedantic, don’t they? Ordinary people don’t care about such things. I am in Taro Okamoto’s group. My logic is “Why don’t you explode?” (laugh) But when I entered into the commercial world, that method was useless.

K: Why?

T: Why? I wonder why. Because a business has to deal with many people. The minority’s art is ......as much as possible...

K: The feelings and interests must be shared to some extent, I guess.

T: Mr. Kishio Suga said that I had to be stubborn but to be easy to understand among the general public at the same time. This might be what Ms. Taeko Tomioka (a poet/writer) said, I think. Recently, what amused me was “The Parking” on the 3rd and 4th floor of the Sony building. That was interesting. Japanese aesthetics is a subtraction. If that was so, I thought I would subtract until the reality is exposed. It’s a crooked way of thinking.

K: Oh, I see, at the end of subtraction.

T: I would subtract more and more.

K: Interesting. That’s how the backstreet is.

T: What calms most Japanese people is trees or nature. They don’t feel composed if a huge building is built like the ultimate subtraction. Mr. Kengo Kuma frequently said, “Trees, trees”, but his “trees” can’t be burnt. They were developed not to be burnt. So, I sometimes argue, saying, “Trees which can’t be burnt are not trees. They are good because they disappear when they are burnt.” That’s how our culture was before we were defeated in the war. When a typhoon came, everything was destroyed. Everything was burnt by fire. Then people built houses on the same site. They were shanties. Then people tried to make houses fireproof, to make them safe and started to build them with concrete and steel. That created big trouble.

K: Noise is like that, right? It is not until there is some deterioration and accumulation, and intervention there, that an interesting reflection is born. However, as time goes by, brand-new places will also become like those places, I think.

T: See, people are good at building, as if to say, “We made it. What do you think about this wonderful space?” I don’t like such a thing. I don’t know it very well, but why can’t they go to the stage where we think it to be somehow interesting? When everyone says, “That’s not good,” I say, “That’s fine.” There are times when I don’t understand what is what and which is which while I am thinking perversely.

K: Architecture is quite unique, I think. If it is clothes, for instance, damaged jeans are sold after being deteriorated over time. But people hate such a thing concerning architecture. Most people want to live in newly built houses. Architecture is in the area where such ideas never come in. Many people want to live in fascinating houses.

H: Isn’t the refurbishment of old traditional houses in fashion?

K: There is the damaged jeans type, but it is not what architects build.

H: Yes, the architects’ side doesn’t want it, but the people who live in them don’t mind.

T: Like the Guggenheim in Bilbao, they want architecture which makes a town look exciting in one go.

K: But as you told us before, isn’t it the difference between building something from the empty land and fitting the shape, using the place which was already there? Speaking of extremes, when making something from scratch, you can create it without a model if you have a blueprint. The architects’ work finishes there, but interior workers, after making a design, are controlled in how much they can realise it. How much they relate to it concretely is different. Starting from an existing thing and from nothing are completely different.

T: There is no place without anything. It definitely exists there somewhere, in the topography, in the air, in the wind. The modern arts and architecture tried to create something out of nothing. Hans Sedlmayr said that abstraction, coincidence and geometry were the core. I agree. But that era has finished. We don’t care about assuming a defiance. So, Mr. Kengo Kuma, who wasn’t particular about anything, was strong. He undertook everything.

K: At the end of this interview, would you like to answer my last question? What is VIC to you?

T: Well, in terms of doing something by myself, I did various things if you look at it closely, even if they were not very unique. But in terms of doing something in a group, we ended our recording. The last was terrible. Everyone was worn out, especially Mr. Noyama. He had made a great effort in our work. But he finally said, “There is no point in filming anymore. There is nothing to record.” Every month, we went to Dairakudakan (dance troupe) and filmed them at their request. It was free of charge to them. He was filming it and I was monitoring. Suddenly, the dancers disappeared from the screen. “What’s wrong?” I looked at him. He was sleeping. It was that boring. Before performers had a feeling that they could transform something by acting out drama and dancers could transform themself by dancing at that time, but in reality people can’t transform themselves. (laugh)

K: I think some people have been able to transform through their movements.

T: As they wanted to transform themselves, they worked with their high spirit, but I thought, “There is no point in looking at them.” I saw a lot of examples of it. When I saw him sleeping, I made up my mind to finish. At first, it was interesting. When I filmed Mr. Kazuo Ohno (dancer) , I thought, “This is great fun.” But in the end, Ri Reisen [Iyoson] from the Juro Kara dance troupe told me from her side, “Next time, could you please film me as I’m doing it like this.” I thought it had no point.

K: It’s the opposite from your initial style, isn’t it?

T: It had become a daily routine. As I needed to survive anyway, I sold video equipment as an information device. It led to my shop specializing in video-tapes on the backstreet.

K: When was that?

T: In 1981 or 1982. The shop led to the present backstreet. We don’t know what is connecting to what. But something in reality is moving and happening, including creating or not creating. This was said by Drucker. New things come from outside, but most people can’t see the chances in front of them. You have to catch it as well as possible. Something is always happening, but you can’t see it. You can’t feel it. It is the same with video. It relates to all sorts of business. There are many cases where it would have been good if you had told me that you liked it earlier, aren’t there? I am interested in many things. You can see it in my “VIC video-tape list”. You can understand what kind of era it was. The content of the recording is messy.

RELATED